|

FRESH STUFF DAILY |

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

SEE ALL SIGNED BOOKS by J. Dennis Robinson click here |

||

Page 2 of 2

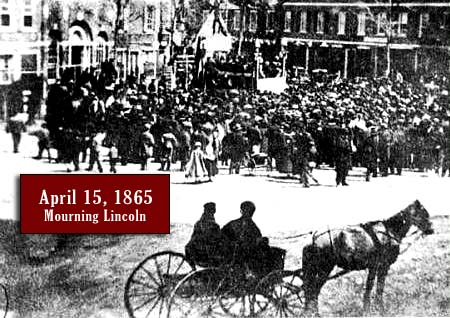

A Legend is Born Local legends tend to oversimplify complex events. One popular story says that the 1865 riot forced Joshua Foster out of town at the close of the Civil War. Portsmouth residents who know local history often add that the mob dragged Foster's printing press down Daniel Street and threw it into the Piscataqua River. None of the local newspapers reported that unlikely detail. But the exaggeration works neatly to round out the elementary myths of the Civil War. In a nutshell -- the Yankees won, the slaves were freed, Lincoln was shot and the Copperhead movement died away. In its coverage of the riot The Portsmouth Journal referred to editor Foster as " a skunk", but noted that the action of the mob was "more deserving of condemnation than even the vile sheet itself." The Chronicle noted triumphantly: "The destruction of the office is, no doubt, the death of the paper -- which is no loss to anyone." But history is rarely tidy and Joshua Foster was far from beaten. On April 19, only nine days after the riot, he published a two-page special edition of the States and Union with help from the Manchester Union press in Manchester, NH. It is a startling document and carried the two biggest stories of Foster's journalistic career. A rare tattered copy of the issue is archived at the Portsmouth Athenaeum. On one side of the broad sheet Foster described in detail his version of the Daniel Street riot. The front side bears the headline: TERRIBLE TRAGEDY! PRESIDENT LINCOLN ASSASSINATED!

Foster's coverage of the assassination of the man he hated appears to be straightforward, respectful and accurate, although without the detail, emotionality and hero-worship evident in other Portsmouth newspapers. Foster's disrespect is embedded in the page design, however. Only two of the seven columns on the page are devoted to Lincoln. Assassination of anyone, Foster noted, is an unacceptable form of political protest. The rest of the page included a transcript of Robert E. Lee's surrender speech, reports from southern newspapers and a letter from Confederate President Jefferson Davis written on April 7 urging southerners to "meet the foe with fresh defiance." The rest of the page includes largely trivial filler including detailed safety instructions on turning off kerosene lamps, jokes, and the story of a man in France who sold his wife for $650. While other papers outlined the assassination story with thick black borders, Foster gave Lincoln no more ink than the account of the raid on his office. What Happened That Day For the record, it is interesting to compare Foster's rarely seen version of the newspaper riot with that of his often-quoted contemporaries. Everyone agrees that the event began when Gen. Robert E. Lee's surrender to Gen. Ulysses S Grant at Appomatax on April 9. News reached Portsmouth the following morning and locals immediately began to party. Work at the shipyard was suspended at noon and here, Foster insists, deliberate plans evolved to ransack the States and Union. Other accounts suggest that the riot was spontaneous, not conspiratorial. Shipyard workers and visiting sailors celebrated at 50 bars open in Portsmouth that afternoon. At a few minutes before 2 pm, Foster says, a man came into the States and Union office and announced that a "committee" was coming to nsist that he hang an American flag out his window. Foster reported that he was happy to do so, as long as there was no compulsion. He told the man that he had no flag in the office and that the one in the Democratic club upstairs in his building had been carried away to another part of the city. Fosters office was on the second floor of a brick building where the US Federal Building now stands. When he looked out the window, he says, a crowd of one or two thousand had gathered below. "It seemed as if all the inmates of bedlam had been let loose to devour us in their causeless wrath," Foster reported. Someone got a flag, Foster says, and three men went through the roof "scuttle" in order to attach it to a wire above the office. The scuttle, a wooden trap door in the ceiling, broke off and fell to the street, hitting a bystander on the head and arm. This inflamed the crowd that began shouting for Foster's life. Unsatisfied with the flag, the "mobocrats" insisted that Foster hold the flag himself and make a speech. He refused. Phillip C. Foster, who in 1973 wrote a response to Brighton's many published accounts, drew his version of the story from his grandmother Lucretia Gale Foster, Joshua's wife. In her words, faced with an angry drunken mob of more than a thousand people, her husband went to the office window and shouted, "Go to Hell!" At that point a handful of friends convinced Foster to duck out the back way. He did as one group smashed thorough the door and another group scaled the outside wall with ladders and crashed through the front windows. As soon as members of the crowd learned that Foster had left the building, they smashed the printing press and threw the pieces from the window. Some carried the metal type letters down to the river and threw them in, giving rise to the legend that the press itself was cast into the Piscataqua. Joshua Foster remained defiant. He vowed to continue publishing his States and Union and suggested that Portsmouth would be better off if the "sneaking coward" editor of the Morning Chronicle committed suicide. The Chronicle, Foster said, was little more than "a hideous ulcer on the face of society". Foster praised the Provost Marshall for his bravery in trying to quell the crowds. He condemned the city for letting the police stand by for two hours before disbursing them. According to local accounts, Foster sued the city for damages and lost. But according to Lucretia Gale Foster, her husband also brought suit against the Navy Yard for its negligence in controlling its workers. Foster was reportedly awarded $2,000 by the government and used that money to get his newspaper back on its feet. Foster, it seems, was far from dead. In March 1868 Joshua Foster started the Portsmouth Evening Times, a daily designed to compete with the Morning Chronicle. The Chronicle complained bitterly that Foster had become the attack dog of ale tycoon Frank Jones, who later became a Republican. Foster sold his Portsmouth papers in 1870. After a failed publication in Connecticut, he returned to his journalistic starting point to begin a weekly Democratic paper in Dover in 1872. A year later, as Portsmouth Herald editor Ray Brighton loved to remind us, Foster introduced the Daily Democrat. There is a tiny fact that Brighton failed to mention. Joshua Foster’s daily Portsmouth newspaper continued under different managers until 1925 when it was purchased and consolidated into -- you guessed it -- The Portsmouth Herald. SOURCES: Constructing Munitions of War by Richard E. Winslow III (1995); Historic Portsmouth by James L. Garvin (1995); Portsmouth: Historic and Picturesque by Caleb Gurney (1902); "Portsmouth Event Affects Local Newspaper," by Phillip C. Foster, Foster's Daily Democrat (1974); They Came to Fish (1973) and Frank Jones, King of the Alemakers (1976) by Raymond Brighton; Granite Monthly (April 1900); plus articles in Portsmouth Journal, States and Union, NH Gazette and Portsmouth Chronicle.

Please visit these SeacoastNH.com ad partners.

News about Portsmouth from Fosters.com |

| Sunday, April 28, 2024 |

|

Copyright ® 1996-2020 SeacoastNH.com. All rights reserved. Privacy Statement

Site maintained by ad-cetera graphics

HISTORY

HISTORY