|

FRESH STUFF DAILY |

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

SEE ALL SIGNED BOOKS by J. Dennis Robinson click here |

||

The Piscataqua River that divides New Hampshire and Maine is the third fastest-flowing navigable river in the world. Okay, readers respond -- but what does "Piscataqua" mean? It is a term much easier to understand if you are a prehistoric Seacoast Indian.

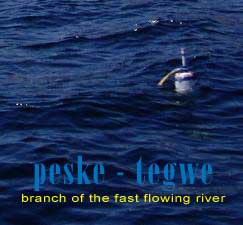

SEE: Guide to Indian Artifacts I tell them, instead, that the Piscataqua River that divides New Hampshire and Maine is the third fastest-flowing navigable river in the world. I don’t really know what that means, other than that the current can be treacherous. Innocent victims have been pulled out to sea in little boats, never to be seen again. Serious sailors have struggled, even died, battling the Piscataqua tides. Portsmouth historian Ralph May tackled the derivation of this Indian word in his book Early Portsmouth History (1926). Forty years later he was still working at the puzzle. In 1966 he published a 20-page booklet entitled "Piscataqua : The Correctness of Use and the Meaning of the Word". The booklet opens with a daunting three-page poem about the river. That poem has always blocked my entrance. This week I took a deep breath and read the whole booklet. Here’s what it says. John Smith used a similar sounding name for this region in his 1614-era map. The precise modern spelling "Piscataqua" first appeared in English writing in 1623, Ralph May says, the same year that David Thompson settled his fishing group at what is today Odiorne Point in Rye. The word eventually appeared as "Pascattaway" and "Pascataquack" and another thirty variations in an era when consistent spelling was of no special value. May gets his propeller caught in the seaweed here. He gets snagged on the variant spellings, searching for meaning that is not there. All of the versions are descended from the Abenaki term (also spelled Abnaki, Abnaque, Wabanaki) used to described the river or the New Hampshire and Maine land in its vicinity. In short, the name describes a place where a river separates into two or three parts. Native Americans defining the word, Ralph May wrote, often extended an arm with two or three fingers splayed apart to illustrate the concept. May offered this definition: "a place where boats and canoes ascending the river together from its mouth were compelled to separate according to their several destinations." Not bad. It is, metaphorically, a place from where people take their separate paths, and in reverse, a place where they come together -- a sort of prehistoric airport or bus terminal. This concept was important for migrant natives who lived in family and tribal groups, moved with the seasons, traveled by river and came together for annual ceremonies and celebrations. The sea was less interesting to them than the many tributaries of the Piscataqua further inland. That’s where the fish are easier to catch and the fur-bearing animals come to hunt. For thousands of years before the Europeans came, Native American tribes had spent part of each year at the falls of the many rivers that lead toward the Piscataqua -- at Cochecho, the Bellamy, the Lamprey, the Exeter, the Oyster rivers and at Salmon Falls. These were their separate destinations branching at Dover Point where the highway rushes above the entrance to Great Bay, our central tidal lake. In his early research Ralph May wrote to Indian language expert Fanny Eckstorm who wrote back to him in 1929, three years after his book was published. All of the errant spellings of "Piscataqua", she told him, would have been recognized as proper by an Indian listener. "Peske", she said, means "branch", and "tegwe" is a river with a strong current, possibly tidal. Piscataqua, "peske-tegwe" to an Abenaki speaker, would likely mean the portion of the river between Great Bay and the sea. While the "Piscataquack" pronunciation would likely refer to the branching off point itself, according to Eckstorm, along Great Bay and Little Bay. She knew best. In her research, Eckstorm traveled on rivers with native-speaking guides – asking questions, listening, imagining. Ralph May studied and rejected a clever anglo-centric theory that the word means "place of many fish" and is derived from the words "Pices" (fish) and "aqua" (water). These words, according to the story, may have been Latin terms picked up by the Indians, taught to them by explorer Martin Pring who reputedly was the first white man to sail up the Piscataqua River in 1603. It seems unlikely that the natives waited thousands of years for just the right Latin phrase to describe their home waters. May also rejected the translations "the great deer place" and "dark or gloomy river" found in a number of sources. He found the definition "meeting of the waters" too vague. A determined scholar, Ralph May tracked down every other river, town, mountain and county in the East with a name resembling Piscataqua. He contacted every local library or historical society and dutifully reported the results in his essay, quoting entire letters from reference librarians and local historians. Most knew nothing. The town of Pascataway in New Jersey, May discovered, took its name from settlers who came there from the Piscataqua region of New Hampshire in 1668 -- another lexicographical dead end. On this issue, to borrow a phrase from George Bernard Shaw, you could hook every reference librarian in New England together and they wouldn’t reach a conclusion. They do not speak Abenaki. The people who did were driven forever from their ancestral homelands by white settlers long before the American Revolution. For Ralph May, nailing down the meaning of his favorite river was a long and winding scientific journey through a mountain of books. But eventually he came to think like an Indian, not a white scholar. The branching point of this swift flowing river is both a visual and a spiritual description. It is the point where decisions must be made and families must part. The river demands no less. After searching four decades, the author came to an understanding of the word, rather than a definition. One does not have to spell or pronounce a word precisely, he learned, in order to recognize the great Piscataqua or to feel its supernatural power. Source: Ralph May, "Piscataqua: The Correctness of Use and the Meaning of the Word," lithographed by the Randall Press, Portsmouth, NH, 1966, 20 pages and from his book Early Portsmouth History, CE Goopspeed & Co, Boston, 1926, Chapter 3. Copyright © 2005 by J. Dennis Robinson. All rights reserved. MORE VERSIONS OF "PISCATAQUA" (click below)

Pascattaway Pascataquack Pescataway Pascaquake Pascattaquacke Pischataqua Paskatoquack Piscataquake Pischataq Pischaqua Pascataque Passataquacke Passataway Piscataway Paskataway Piscattowa Pescataway Pascatoquack Pascaquacke From: Ralph May, "Piscataqua: The Correctness of Use and the Meaning of the Word," lithographed by the Randall Press, Portsmouth, NH, 1966, 20 pages and from his book Early Portsmouth History, CE Goopspeed & Co, Boston, 1926, Chapter 3. Please visit these SeacoastNH.com ad partners.

News about Portsmouth from Fosters.com |

| Friday, April 19, 2024 |

|

Copyright ® 1996-2020 SeacoastNH.com. All rights reserved. Privacy Statement

Site maintained by ad-cetera graphics

Smuttynose Murders

Smuttynose Murders