|

FRESH STUFF DAILY |

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

SEE ALL SIGNED BOOKS by J. Dennis Robinson click here |

||

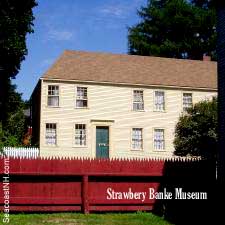

Like Paul Revere, historian Dorothy Vaughan woke Portsmouth citizens to an invasion. Progress, she said, was destroying the colonial character. The city responded and preserved over 30 buildings in Strawbery Banke Museum. It all started in June 1957 – or did it? The simple truth is – there is no simple truth.

Time compresses history much the way it compresses coal, but faster. It only takes a few years to squeeze a legend from layers of facts. Like a diamond, the legend is attractive, crystal clear and almost indestructible. Excerpted and adapted from STRAWBERY BANKE:: A Seaport Museum 400 Years in the Making by J. Dennis Robinson. Click below to purchase our book. A Star is Born

Inspired by this speech, local citizens rallied to save more than two dozen colonial buildings from the bulldozers of urban renewal. Puddledock on the Piscataqua River, the site of one of the nation’s oldest settlements, was transformed from a run-down neighborhood into a 10-acre museum. Dorothy Vaughan, who died just shy of her 100th birthday last year, became the first president of the new nonprofit agency. Strawbery Banke Museum thrives and is approaching its own 50th anniversary. That is the short version. Examined closely, legends and diamonds reflect many facets of the truth. Taken at face value, they can blind us to the facts. We may forget, for instance, that Strawbery Banke Museum was a group effort. A lot of people made it happen. This is really a more interesting and complex tale of a town saving itself. A Quick History Lesson. No buildings remain from the small 1630-era colony of settlers who discovered a bank of wild strawberries about two miles in from the mouth of the Piscataqua River. The oldest house in modern Strawbery Banke dates from 1695. Portsmouth became an important world port in colonial days, but it peaked early. The sophisticated aristocratic city faded in the early 1800s. Portsmouth turned to shipbuilding, but never regained its prominence. A nostalgic sense of faded glory, a longing for wealthier days became ingrained in the Portsmouth culture. The city’s fine colonial mansions, weathered and crumbling, served as a reminder of better days gone by. Portsmouth’s South End mirrored the city’s economic decline. The Puddledock waterfront area evolved from a bustling world tradeport to a densely populated working class neighborhood. Water Street became the local "combat zone" as well as its "melting pot" of immigrant arrivals. In the 1950s this neighborhood was officially designated as "blighted" by a federal study and slated to be completely torn down. Instead, for the first time in American history, urban renewal combined with historic preservation Continue with WHO STARTED STRAWEBRY BANKE?

Portsmouth Practices Preservation The saving of 27 houses and the start of Strawbery Banke was the culmination of a series of events that came to a head in 1958. But it was not the first time that local citizens had come together to preserve its unique architectural heritage. The city’s first pocket guide to historic houses was published in 1869. A tourist boom after the Civil War drew national attention to the faded colonial seaport. The process began one house at a time. The local trend toward individual house museums began in 1908 with the opening of the Thomas Bailey Aldrich House on Court Street, now part of Strawbery Banke. The Wentworth-Gardner house (1760) and the John Paul Jones House (1758) opened to the public in the 1920s, followed by the Warner House (1713) a decade later. The Moffatt-Ladd (1763), Jackson (1664), Langdon (1784), Lear (1740), Wentworth-Coolidge (1753) and Rundlett-May houses (1807) followed. But no one thought to preserve an entire neighborhood. The waterfront saw a massive change when Charles Prescott died in 1932 leaving a $3 million fortune to his two sisters Josie and Mary. They used the money to buy up and destroy all but two buildings on the water side of the street to create a public park across from what would later become Strawbery Banke Museum. The idea of turning the waterfront into a tourist Mecca actually dates to the 1930s. Architect John Mead Howells, a Kittery summer resident, conceived a plan to create an historic maritime village. With naval historian Stephen Decatur he hoped to preserve the buildings and rebuild a replica of Portsmouth in its heyday, complete with tall ships. The National Park Service took an interest in the Howells/Decatur plan and listed the Portsmouth waterfront among its top ten potential projects. A government-sponsored survey examined over 200 buildings in the Puddledock area. But the National Park Service took a pass on Portsmouth. In 1935. The idea was not financially feasible. Howells and Decatur tried shopping their Maritime Village idea to other backers, but no funding was found. In 1940, Capt. Chester Mayo of the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard spearheaded a plan to survey and restore the waterfront neighborhood. Librarian Dorothy Vaughan was among the volunteers. But Mayo was transferred out of town, war intervened and the plan lapsed. Continue with WHO STARTED STRAWEBRY BANKE?

How Everything Changed It was not a single speech that awakened the city to the concept of a community-owned museum at Strawbery Banke. It came from many speeches and a lot of political wrangling. By 1955 the Puddledock area was being considered for a federal urban renewal project that would flatten more than 200 buildings and build garden-style apartments for rent. The "blighted" neighborhood between Marcy and Washington streets was on its way to becoming an official "slum" in the eyes of the Federal Housing Authority. While that study was going on, other factors were kicking up interest in Portsmouth preservation.

By March 1958 the cards were on the table. Federal interest in the urban renewal of the Puddledock region was waning. Government estimates showed that tearing down the buildings to install garden apartments was not financially viable. The $835,000 of federal money allocated for urban development in Portsmouth was about to disappear. The "Colonial Portsmouth Committee" suggested marrying the Colonial Village idea with the existing Urban Renewal project since there were no private funs available. It was a tricky marriage from the start. In order to save the historic region, Puddledock residents were displaced to new low-income housing. Houses were taken by eminent domain. Many were razed. Some were saved. In the end, the laws of New Hampshire had to be rewritten to allow the project to move ahead. But the idea had reached critical velocity. In May 1958, following a public hearing, the city authorized a $200,000 bond. City council members approved the plan and it passed through a public hearing. In November 374 incorporators signed the papers to create a nonprofit organization offering shares at $10 each. Strawbery Banke Inc. was born. The museum opened in 1965. It has changed enormously since its founding days – but that is another legend. Copyright © 2006 by J. Dennis Robinson. All rights reserved. Robinson is currently writing a book about the history of Strawbery Banke and invites all readers with unique information to contact him via this web site at SeacoastNH.com before October 2006. This article from the book STRAWBERY BANKE:

Please visit these SeacoastNH.com ad partners.

News about Portsmouth from Fosters.com |

| Sunday, April 28, 2024 |

|

Copyright ® 1996-2020 SeacoastNH.com. All rights reserved. Privacy Statement

Site maintained by ad-cetera graphics

HISTORY

HISTORY

According to legend, Portsmouth librarian Dorothy Vaughan started Strawbery Banke Museum. She gave a rousing speech to the Portsmouth Rotary in 1957. She warned the business community that the Old Town by the Sea was crumbling. Portsmouth was selling its soul in the name of progress. Bowling alleys, honkytonks and stores with plate glass windows and neon signs were taking the place of grand colonial homes. Pretty soon, she said, Portsmouth would look like Main Street, USA.

According to legend, Portsmouth librarian Dorothy Vaughan started Strawbery Banke Museum. She gave a rousing speech to the Portsmouth Rotary in 1957. She warned the business community that the Old Town by the Sea was crumbling. Portsmouth was selling its soul in the name of progress. Bowling alleys, honkytonks and stores with plate glass windows and neon signs were taking the place of grand colonial homes. Pretty soon, she said, Portsmouth would look like Main Street, USA.