|

FRESH STUFF DAILY |

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

SEE ALL SIGNED BOOKS by J. Dennis Robinson click here |

||

The plan was to revive the crumbling Portsmouth, NH waterfront into a vibrant Maritime Village. The year was 1935. A famous architect and naval historian made a valiant attempt with a clever project – too clever, unfortunately, for Uncle Sam

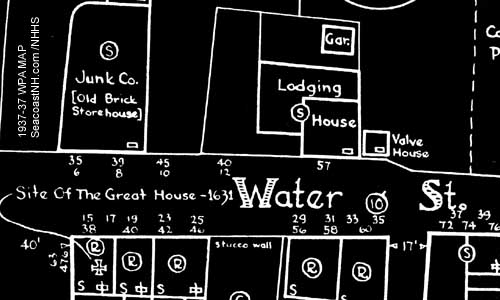

READ ALSO: Who Started Strawbery Banke? The idea to turn the Portsmouth waterfront into an outdoor history museum did not start in 1957 with the founding of Strawbery Banke. Few people know that two decades earlier the federal government seriously considered converting the South End into a National Park. A recently rediscovered 1936 WPA blueprint shows detailed plans for a massive restoration project in what was then an ancient and dilapidated neighborhood along Marcy Street. The original plan, designed to create jobs during the Great Depression, called for restoring 175 old Portsmouth houses and moving or demolishing 75 "ugly new buildings".

The Portsmouth Maritime Village was the brainchild of two Kittery Point summer residents, architect John Mead Howells and naval historian Stephen Decatur. Both men came from famous families. Born in Portsmouth in 1886, Stephen Decatur IV was descended from a Revolutionary War hero whose son Stephen Decatur Jr. defeated the dreaded Barbary Pirates only to be killed by another naval officer in a duel. John Mean Howells was the son of William Dean Howells, an influential editor and writer and close friend of Mark Twain. The two influential men pitched their idea to the mayor of Portsmouth in 1934, but with little reaction. They then presented it to the National Park Service in 1935. Parks pitched it to the Works Progress Administration (WPA) under Franklin Roosevelt, the "New Deal" President.. Federal officials quickly agreed that Portsmouth was among the ten best sites in America for an outdoor history park. When Congress passed the Historic Sites Act in 1935, hope for the Howells-Decatur proposal blossomed. The Act summed up the very essence of the Portsmouth Project when it promised "to provide for the preservation of historic American sites, buildings, objects, and antiquities of national significance . . . for the inspiration and benefit of the American people." No other city in the nation, Decatur and Howells told the National Parks Department, could offer an intact waterfront neighborhood with buildings dating to 1695. First settled in 1631, Portsmouth’s Puddle Dock area could claim to be one of the oldest neighborhoods in America. But its peak as a major world shipping port ended in the early 1800s and the area had been in decline ever since. Howells and Decatur proposed to restore the entire waterfront area to the way it looked in 1800 when Portsmouth was in its heyday. Rather than tear down or modernize the decayed wharves and warehouses that still stood along the water, Decatur and Howells wanted to repair them. They also proposed to dredge out the Puddle Dock tidal inlet. (It was filled in early in the 20th century and is now a flat open area inside Strawbery Banke Museum.) When restored, the "Cove" would look as it had when the first Piscataqua settlers arrived from Europe. Local boat builders would then be hired, at government expense, to build four wooden boats, including a "barcantine" and a flat-bottomed gundalow, that would be docked in the restored cove. CONTINUE with WPA NATIONAL PARK

The Portsmouth economy was stagnant in the 1930s. Jobs were hard to come by and, according to a WPA survey, a large portion of the families living in Puddle Dock were on government relief. Up to 1.5 million motorcars passed through the center of town each summer and over the new Memorial Bridge leading to Maine. But few cars stopped. The Maritime Village plan cleverly diverted all that traffic through the restored waterfront with its colonial homes and tall ships. The goal was to lure tourists out of their cars and into Portsmouth shops, restaurants and historic house museums. Tourists could buy a "strip ticket" allowing them to see any of the museums in "Old Portsmouth" for one price.

The proposal called for the entire portion of the town to be taken by eminent domain. All 63 property owners are listed in the WPA proposal with a plan for compensating them. An estimated 250 families lived in the Restoration Area during the Great Depression, an area that extended beyond Puddle Dock down Marcy Street as far as Pleasant Street. Many of the families were renters, newly arrived immigrants living on subsistence incomes. Howells and Decatur hoped to move those families to clustered housing developments nearby that included gardens, parks and playgrounds. They also planned to draw their work force from the same unemployed people living in the area. Puddle Dockers, therefore, would be paid by the government to restore their own neighborhood, which the planners felt would improve their sense of community pride. But to make this happen, the neighborhood had to be officially declared a "slum" by the federal government. The dilapidated houses, a series of junkyards, the ethnic diversity and low income of its residents all contributed to the government classification. Although the local "red light" district on Water Street had been largely cleaned up since 1912, the reputation clearly influenced the official classification of the region as a "blighted" zone. For historian Decatur, the best part of the plan was that it kept history alive. By restoring old homes and building old boats in the area, a host of fading maritime trades could be recaptured and passed on to future generations. As in the 18th century, the Portsmouth waterfront would again be home to blockmakers, sailmakers, joiners, blacksmiths and the like, employed to reconstruct historic tall ships for the maritime tourism industry. Artisans would also be able to restore and purchase dilapidated homes in the area with government assistance, thus allowing poor renters to become homeowners. A key member of the National Park Service visited Portsmouth in 1935 and reported enthusiastically to his director. "I am convinced that such a development would rival Williamsburgh in popularity," he wrote. Portsmouth was frequently compared to the recently opened outdoor museum in Virginia. Ten years later in 1944, still pushing the Portsmouth maritime village idea in a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, John Mead Howells trumpeted the waterfront project as even "greater than Williamsburgh". Portsmouth was more authentic than other "recreated" museums like Sturbirdge Village, he argued, since all the original colonial houses, taverns, mills, wharves and warehouses already existed.

Even though he continued to promote the project for years, John Mead Howells quickly suspected that the Interior Department did not have pockets deep enough to rehabilitate an entire city sector. Appealing to the financially strapped New Hampshire seaport was simply wasted energy. "In Portsmouth there is nothing," he wrote to a friend in 1935, "the last of the aristocracy is falling – it is a town of tradespeople and politicians without interest in old houses." But the rollercoaster ride had just begun. The National Parks agency was intrigued and by 1936 Portsmouth was among the top three sites in the nation slated for investigation along with Annapolis, Maryland and Nachez Mississippi. "It seemed for just a fleeting moment," according to architectural historian Charles B. Hosmer, Jr., "that the plan would work – that the National Park Service could get the money and the personnel to go into Portsmouth with a restoration program." But the ambitious Decatur-Howells proposal was ahead of its time. Even though the $2.5 million estimate was one-tenth of the cost of Williamsburg, the Roosevelt Administration passed on Portsmouth. Howells must have been especially frustrated when he learned that on April 10, 1940, while making a pre-war tour of the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, President Franklin Roosevelt passed right by the proposed maritime village site. In his third and final visit to Portsmouth, Roosevelt road in an open car up Daniel Street and across the Memorial Bridge just 100 yards from Puddle Dock. The Decatur-Howells plan lost momentum during World War II and, despite attempts at revive it, faded in history. Only a few Portsmouth residents ever knew it existed. Howells did have a Plan B. He attempted to contact John D. Rockefeller, who paid for much of the Williamsburg renovations, but without success. He reached out to automaker Henry Ford who donated millions to his own historic village reconstruction in Michigan. But Ford too was uninterested in the sleepy Portsmouth waterfront. "I suppose we can hardly blame him," Howells responded on learning of Ford’s polite refusal. "We will have to carry on some other way." That way did not come for two decades when in 1954 the federal government again focused its attention on the Puddle Dock area. This time, however, the plan was to bulldoze every building in the neighborhood to make way for a housing complex of "garden apartments". In 1958, following a public surge of interest in historic preservation, Strawbery Banke Inc. was created, although the museum did not open to the public for another seven years. Twenty-seven historic buildings were saved from the bulldozers of urban renewal, but scores of Puddle Dockers were displaced. John Mead Howells died soon after the Strawbery Banke project was begun. Stephen Decatur lived just long enough to see the project come alive, but it was not the Maritime Village they had envisioned – funded by millions of National Park dollars and bustling with costumed ship builders on restored wooden wharves and cobblestone streets. The days of Portsmouth’s great China Trade had ended long before, and would never come again. Copyright © 2006 by J. Dennis Robinson, All rights reserved. This article is adapted from Dennis Robinson’s upcoming book that chronicles the 400-year history of the Puddle Dock area. The book is scheduled for publication in fall 2007. Robinson is editor and owner of SeacoastNH.com, a popular local web site covering Seacoast history, travel and culture. Please visit these SeacoastNH.com ad partners.

News about Portsmouth from Fosters.com |

| Friday, April 26, 2024 |

|

Copyright ® 1996-2020 SeacoastNH.com. All rights reserved. Privacy Statement

Site maintained by ad-cetera graphics

HISTORY

HISTORY

And there was more. An updated 1936-7 version of the proposal called for a bridge leading to the city-owned Peirce Island, site of the nation’s only intact earthwork fort, dubbed Fort Washington during the American Revolution. (The site has since become a sewer treatment plant, and its historic value destroyed.) The planned Restoration Area also included the William Pitt Tavern, then nearly in ruins, Point of Graves colonial cemetery, a revamped tidal mill, the restored "swing bridge" and the historic Liberty Pole, as well as the site of the 1631 Great House. The plan also called for the restoration of Portsmouth’s original colonial statehouse that once stood in the middle of Market Square. Although a small piece of the building had survived, Howells and Decatur hoped to rebuilt it into a grand welcoming center for the hordes of tourists that were sure to come.

And there was more. An updated 1936-7 version of the proposal called for a bridge leading to the city-owned Peirce Island, site of the nation’s only intact earthwork fort, dubbed Fort Washington during the American Revolution. (The site has since become a sewer treatment plant, and its historic value destroyed.) The planned Restoration Area also included the William Pitt Tavern, then nearly in ruins, Point of Graves colonial cemetery, a revamped tidal mill, the restored "swing bridge" and the historic Liberty Pole, as well as the site of the 1631 Great House. The plan also called for the restoration of Portsmouth’s original colonial statehouse that once stood in the middle of Market Square. Although a small piece of the building had survived, Howells and Decatur hoped to rebuilt it into a grand welcoming center for the hordes of tourists that were sure to come.