| Peace Corps Letter from Senegal |

EDITOR AT LARGE

Rebecca Perkins was born and raised in Seacoast, New Hampshire so there was nothing familiar about life in West Africa. Or was there? Rebecca reports on the lessons she taught as a Peace Corps business consultant in Dakar – and the lessons she learned. An exclusive online letter from Senegal to SeacoastNH.com.

RELATED LINK: Seacoast Nh Black History

A Long Way From Home

A Stratham, NH Woman Finds Her Way in West Africa

By Rebecca Perkins

SeacoastNH.com Exclusive

Wait, what am I teaching again?

Wait, what am I teaching again?

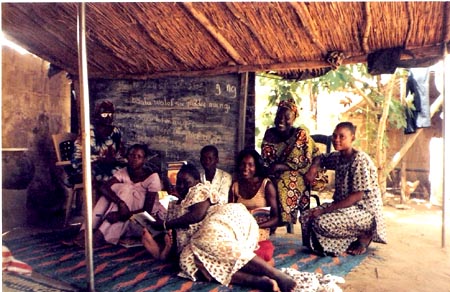

This phrase keeps running through my head on a hot morning as I stand beneath a thatch roof in a dusty compound. Glancing at the sheep chewing in the background, I hold up a red bill from our training game and ask, "Bi, naata la?" This bill, how much is this one?

I am met with blank faces, some guesses. "Dix mille!" Ten dollars.

Sigh. "Deetdeet. Naata la? Keenen?" Nope. Nobody knows? Anyone?

I turn and write on the chalkboard, one that is so old and weathered that the black surface resembles peeling paint. I scratch out a "20" and turn back around. Another question:

"Benefice ci chapeau, naata la?" How much is the profit, then? I hold up the same bill. A bunch of faces stare at me hopefully, but nobody says anything. I point obviously and make goofy faces at a young girl in the front row, encouraging her.

"Vingt mille!" She says, giggling at the white person trying to speak her language.

"Voilà!" I say, smiling and turning back to the chalkboard. I let my face fall for a minute, my mind racing. This is going to be a long day.

It was never obvious I was going to end up in the Peace Corps. I spent most of my life right here in New Hampshire. I grew up, worked in my mom’s restaurant, went to college. I love the small towns of New England, the windy country roads and the fall foliage. My family and friends, however, didn’t seem surprised when I called them shortly after graduating from college.

It was never obvious I was going to end up in the Peace Corps. I spent most of my life right here in New Hampshire. I grew up, worked in my mom’s restaurant, went to college. I love the small towns of New England, the windy country roads and the fall foliage. My family and friends, however, didn’t seem surprised when I called them shortly after graduating from college.

"I’m going to Africa!" I said. My mind turning with images of dark desert expanses and women in bright tunics. "I’m going to be a Small Business Volunteer in West Africa for two years!" I said the phrase as if I knew what any of it meant. Maybe grass huts? Lots of insects? Some terrifying disease that would send me home?

"We all knew you’d find some way to save the world, Becca." The well-known parody of my career. Maybe it was obvious.

I graduated from Dartmouth in June 2004 with a major in Comparative Politics and a minor in International Economics. As graduation drew nearer, I was trying to find the best way to start my career…without knowing exactly what that career was. Saving my tiny slice of the world came somewhere close. Late in May, I was accepted into a few different grad school programs and the Peace Corps. Great choices, ones I still felt overwhelmingly lucky to have.

I sat down with one of the administrators at my college who had been in the Peace Corps in 1994. "What do I do?", I asked.

I’ll always remember the clarity of his response. "It’s a no-brainer. You will never get another opportunity like the Peace Corps. To live at that level, live inside of another culture like that- it’s amazing. And Peace Corps is the only program like it. But it’s your choice."

As the Peace Corps says- "Life is calling. How far will you go?"

So I went. Packed up my bags with what I thought I’d need in Africa for two years, which included few clothes or electric appliances. Lots of medicine, and a big journal. I flew down to Philadelphia for three days of prep, and met the people I’d be spending two years with. Then they bussed us up to JFK, and one Wednesday night we took off for Africa.

CONTINUE to read Letter from SENEGAL

NH Peace Corps Worker in Dakar (consinued)

My first memory of Senegal was seeing the coastline of Dakar outlined suddenly against the Atlantic. Orange street lamps and charcoal fires pierced the early morning dark. As our training group took their first ride through the capital city, all of the things I had read floated through my head. Dakar is a dense capital city of two million people in a country of 10 million. There is urbanization and there are squalid living conditions, a lack of clean drinking water, sewage in the streets. My eyes burned from exhaustion and pollution and all I could think was -- I’m so glad I came.

That bus ride will forever stay in my mind – and stomach. I had traveled some in college, but I rarely saw an inner city of America, much less the poverty that now struck me. But then we passed through the city and out, into the surprising green of the late rainy season. Here the disparities of Senegal struck me, and they run deep. There are supermarkets in Dakar and BMW dealers and flat screen TV stores. But 15 minutes from my house in the north are villages unchanged by time. Women bring water from the river and search for wood for their cooking fires. Senegal is just below the Sahara on the west coast of Africa. The desert is to the northwest and the rainforest to the South. There are over 10 different clans and languages, 11 administrative regions and three religions. But the country is predominantly Muslim, village-based, and proud to be Senegalese. A sense of optimism still springs from the recent election, in which the opposition won for the first time since independence. With this, Senegal became a "real democracy" in the shaky landscape of African democracy. We have little trouble with corrupt officials, roadblocks, or lack of transparency.

The economy is as disparate as the geography. Our group is formally known as Small Enterprise Development Volunteers. We are assigned to transfer our skills and knowledge to the Senegalese. It is a dauntingly vague job description, but it has given us the freedom to really address the various needs on the ground here. Our official program goals fall under four objectives: (1) training entrepreneurs to "grow" their businesses; (2) creating information and market links; (3) helping youth and women enter the workforce; and (4) promoting ecotourism as part of Senegal’s development.

It is hard to define the focus of a SED volunteer. The variety of our work is remarkable. We are not usually assigned to any specific person or project; though there are exceptions; we are just sent out into our cities to find work, supervised by the Ministry of Family. Volunteers may work with artisans and bakeries, for example, teaching business classes, then staying behind the scenes to provide gentle guidance. Some assist groups of women to with money, teaching them how to make soap or form a savings club. Others consult with Mayor’s offices on city development. We teach the benefits of a having a simple accounting system. Some work in French, with educated entrepreneurs; others in local, African languages with less sophisticated groups. We get two months training in language and culture before spending two years at our selected site. It’s a tough job.

And that’s how I ended up under a thatch roof in Africa watching a sheep and writing on the blackboard far from the snows of New Hampshire.

We were playing a game as part of my training session on Marketing. That’s a concept as familiar as the air we breathe at home, but here it is a mysterious foray into low-price competition and a dizzying variety of products. In this game in just four days, participants explore an imaginary month in business. They buy material and sell "hats," made from little pieces of paper they design. Players get a loan at the beginning of the month and they must pay it back at the end. They have to divide their money between investment in their business (buying more material), saving money in the bank, and providing for their family. The focus of the game is to cement the concepts of financial planning and investment in their businesses. The player who makes the most hats always wins. The capitalism we grew up with in America, hasn’t arrived here yet. My job is to bring it.

My class was a women’s group that makes juice, tye-dyed clothing, incense, and other things. They seemed motivated, traveling over an hour from where they lived the first time to find my house. The group already had its movers and shakers. We consulted. They checked me out. I got to know their business- for about five months before we picked out dates for the training session. By then, I felt I understood – a little. Their boutique was on a back alley in a remote quarter. We set up our four-day session in early May, playing a game for two days and spending two days on what products to sell, at what price, where, and how to tell the world about them.

As soon as the workshop started I felt like I was the student. I quickly learned that these women’s minds worked in vastly different ways from mine. I also discovered that they were, for the most part, letter and image illiterate. I’m not sure why that surprised me so much: I knew that a lot of women here couldn’t write, and had been told that illiteracy often includes image illiteracy. Amazingly, I was trying to increase their business capacity -- for buying and selling and for complicated operations - and they couldn’t even add. They couldn’t read numbers. How, I wondered, had they gotten this far?

That question started me down the right path. Just because these women couldn’t do math or read didn’t mean that they couldn’t analyze or learn to sell things better. But how?

CONTINUE to read Letter from SENEGAL

NH Peace Corps Worker in Dakar (consinued)

The first day of our Marketing game was a minor disaster. I was expecting questions shooting from every direction as everyone followed my instructions. Instead the women wanted to bargain with me for the price of things. They wanted to resell the things they bought to provide for their families. They wanted to put all of their money in the bank. They wanted to buy lots of sodas in case guests came over. I asked if, perhaps, it wasn’t better to buy rice? They wanted to change the rules. By the end of the first session, I was exhausted, fascinated, and uncertain how to proceed.

I started the discussion after the game, arguably the most important part. We started by paying back the loan. Then we calculated the profits of each group and counted how many hats they had made. I put them up on the board, and asked if they noticed anything. Silence.

So I went through each column and said, "This team made how many hats? … Good. How much profit did they make?"

One group was unable to repay their loan. They joked about buying too much soda and being sent to the Gendarmerie (police). But something was starting to whirl.

"She couldn’t pay her loan back because she didn’t put her money in her business," one woman said.

"Good, why is that?" Silence.

"Do you make profit on putting money in the bank?", I asked.

More women this time. "No. And you don’t make money on soda either." A jibe, but a good observation.

"Right. What did the winning team do? How many hats did they make?"

"They made the most hats. They spent their money on their business. They made a profit. Then they could pay their loan back. You have to spend money there first."

As the conversation became more and more participatory, my smile grew. All the smarts were there. There were just a few skills missing. I went home and slept on it. The puzzle was unraveling.

For the next two days we went over the jargon of Marketing. The discussions were engaged for the most part, though there were some concepts that just didn’t stick. I could tell I was putting some new ideas on the radar screen, but I wasn’t sure my ladies were going to walk out of here and suddenly start slashing prices and printing flyers. In fact I didn’t know what to expect out of my first Peace Corp training, but that’s what made the last day all the more rewarding.

We came together on that fourth morning, everyone tired but glad it was the last day. I set the game up. After the discussion, I told them, we would hand out diplomas. This time they were engaged. I sensed a distinct desire to play the game and to apply their new skills.

This time I had some new instructions to add into the game. First we went over the money. I held up each bill, one by one, and asked the women how much that bill was. We reviewed, then I asked about the rules of the market. Can you resell? Can you change how you design the hats? Very slowly we went through the rules and how to figure profits for each week. We did the math for buying materials and for selling finished products, and for calculating the difference. Lots of women participated, and then helped those who weren’t getting the right answers. They were encouraged by being included and shown. I stood at the board and asked – "What should I write down to calculate the profit between 180 and 120?" They told me. It wasn’t macro-economics. It was not in my job description. This was just simple subtraction. But it was something important. Now I understood. I knew why I was here.

The Peace Corps has not been easy. I get to see my family and friends for about three weeks out of 26 months. I had to leave everything and everyone I knew behind to spend months struggling with every minute of every day learning a new job and two new languages. When you agree to the Peace Corps odyssey, you don’t know where you’ll be living or what, exactly, you’ll be doing -- but as I have come to find out, that is certainly the gem of the experience. Before leaving New Hampshire I was mystified by all the other parts of the globe. It is fair to say I was idealistic and naïve. Arriving in Africa I was, at first, dangling from an open drawbridge over a cultural abyss. Nothing I had read or learned about the political and economic systems of the world had really prepared me for the world itself.

Now I’m different. I’ve learned an African language. I’ve become part of a family that looks nothing like me. I am the first sister my five Senegalese brothers ever had; I am the first professional woman most women and girls here have met. I eat out of a bowl with eleven other hands sitting on the floor. We talk. We learn. We trust one another. We share our dreams. In an age of clashing cultures and anger, I can’t think of a more powerful tool than personal contact or a better system than the Peace Corps.

Copyright (c) 2006 Rebecca Perkins and SeacaostNH.com. All rights reserved.