| My Brother Bob |

BREWSTER’S RAMBLES #139

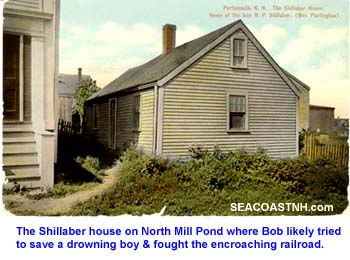

In this rare guest essay, BP Shillaber tells the story of his brother who lived by the North Mill Pond. Brave, simple, hardworking, brother Bob never lied, but often cursed. He risked his life to save a drowning boy, never struck his children, and sued the railroad when it crossed his land.

BREWSTER's RAMBLES #139

EDITOR'S NOTE: BP Shillaber was brought up on the NOrth Mill Pond are of Portsmouth. Shillaber went on to fame in Boston, and this reminiscence was printed in the Portsmouth Journal by editor CW Brewster. This article includes his opinions and may not reflect current research or current values. From Brewster’s Rambles About Portsmouth, 1869 exclusively on SeacoastNH.com. – JDR

THE genuine truthfulness of the following story, from the genial pen of our old townsman, B. P. Shillaber, Esq., as well as its lively account of no less a character than Commodore Mifflin or Toppin Maxwell, induces us to give it as one of the Rambles. Like the two above named, "My Brother Bob" had his home on the South shore of the North Mill Pond. – CW BRewster

READ MORE on BP Shillaber

It was the remark of a distinguished orator who once discoursed about the Father of his Country, that "G. Washington was not a loud boy." I may, with some propriety, apply the same remark to my brother Bob. He is not a "loud boy," in the sense wherein the term loud might be supposed to apply. He does not stand at the street corners and brawl, to the disturbance of neighborhoods; he has no particular fancy for the boisterous; but he is a quiet man, full of good sense, practical to a fault, honest, plain spoken, industrious, prudent. He possesses very little of the ornate or ornamental, and yet he attracts by qualities the opposite of those which usually control. A hardy, gnarled, rough man, yet he is respected more for his integrity of character, and the qualities enumerated, than hundreds who wear far better clothes and make more pretension to refinement. Bob is not an Adonis, for personal grace is not a quality much to be vaunted of in our family, compensation being found in those excellences which the best people discern.

It was the remark of a distinguished orator who once discoursed about the Father of his Country, that "G. Washington was not a loud boy." I may, with some propriety, apply the same remark to my brother Bob. He is not a "loud boy," in the sense wherein the term loud might be supposed to apply. He does not stand at the street corners and brawl, to the disturbance of neighborhoods; he has no particular fancy for the boisterous; but he is a quiet man, full of good sense, practical to a fault, honest, plain spoken, industrious, prudent. He possesses very little of the ornate or ornamental, and yet he attracts by qualities the opposite of those which usually control. A hardy, gnarled, rough man, yet he is respected more for his integrity of character, and the qualities enumerated, than hundreds who wear far better clothes and make more pretension to refinement. Bob is not an Adonis, for personal grace is not a quality much to be vaunted of in our family, compensation being found in those excellences which the best people discern.

An Odd Character and a Hero

My brother Bob is a character, and from the point to which my memory recurs, he has maintained the same position in the estimation of the people as now. It will not do to call him an old man yet; and though years have severely tussled with him, and taken a little away from his elasticity, it has added to his wisdom, and less mpulsiveness characterizes his speech and actions. For instance, he would scarcely now do as he did years ago, when the little boy was drowned in the pond near which he lived: -- throw his clothes off piece by piece as he ran to the rescue, and almost naked venture among the

crackling and brittle ice, breaking beneath his every moment, in his humane endeavor. That half hour of fruitless effort, in the eyes of the assembled town, covered him with glory -- the only covering he had, until his clothes were brought him, and he had made his toilet on the hard-set ice, within a few yards from where the poor boy met his fate.

Neither would he do as he did at the time the boys got upset in the boat, when with no other means of rescue than a half-hogshead tub, he gallantly pushed from the shore to aid them. With a bold spirit, actuated by the warmest feelings, Bob had no thought of danger or reward, though he sometimes found compensation in shaking those whom he benefitted for the trouble they had caused him; and there were frequent opportunites.

He was always a favorite of the boys, and his boat on Wednesday and Saturday afternoons was an object of great competition, for he had a water privilege then on the pond, which a railroad many years since cut off, leaving Bob minus a small income, and a prospective suit against the corporation, in case they refuse to compensate. I can recall many instances of juvenile charter parties for navigation upon the North Mill Pond at such times, and Bob was as well pleased in their sport as though he were not to receive the dime, or less, in payment. Grave and busy men, often, in referring to those times, make mention of that dear delightful sail upon the little pond, then,however, larger considerably than the Atlantic, and speak of Bob in the kindliest spirit of remembrance, recalling him by some amusing anecdote that gave a zest to the good old time.

But there were times when he would swear like a tornado, if such expression may be employed, when juvenile depredators attempted to overreach him; and it has been said that in his earlier days there was more profanity in him to the square inch than in any one around. This, however, has changed for the subdued temper that years bring with them, and but moderate scope is allowed for passion.

CONTINUE with MY BROTHER BOB

CHARACTER SKETCH OF BOB SHILLABER (continued)

Stories About Bob

Speaking of this, I was wont to try him fearfully in the olden time, and well did I rue it in the lofty indignation that fired him; but now, a right philosophy that submits, murmurless, to destiny, governs his conduct to me. This must be the case, else would he denounce me for my failure to answer his letters, and the other indignities of neglect and silence. Even when he called upon me in town in the drive of business, and I begged him, for heaven's sake, to go till I was at leisure -- a rudeness which I repented of in dust and ashes -- he turned without a complaint, and I did not see him again for six months. In reply to an abject apology I made, he said it was all right; he knew me well enough to believe that I was actuated by right motives, and he had no cause to fret about it. I wish, for myself, that such understanding could more universally prevail; that, when in our honesty we use a friend in this manner, he might not imagine an offence and abuse us for the virtue of candor, which may be the only one we have.

Candor is a virtue which Bob especially possesses. He was entrusted for many years with the care of the Court House, in the town where he lives, and was intimate with those comprising the Bench and Bar; Pierce, Christie, Hackett, Marston, Hayes, Eastman, Harvey, by all of whom he was held in high regard -- one of them, who was after-President, having borrowed money of him, upon which he based a claim for an office under his administration, that he didn't get. He was, as I have intimated, not a very dressy person, therein proving an exception to a rule of our family, and strangers underrated him on account of it. A plain suit of clothes, perhaps a green baize jacket, his collar turned back, cravatless, revealing his stout neck, presented an appearance somewhat different from the beau monde, but it was tolerated by all those who were not more nice than wise. There was but one who ever attempted to meddle with him on this point, and he tried it but once.

Bob knew everything that had ever transpired in town. It was said of him by an admirer, somewhat irreverently, that he was next to Omniscience in penetrating human secrets. He had an intuition that was infallible, and could read men like a book. Concerning this one alluded to, Bob had obtained the fact that he was owing a large tailor's bill in town, about which there was some fear. As Bob entered the Court House one morning, there was an extra number of lawyers present, and the individual named among them.

"There, gentlemen," said he, pointing to the green jacket and the open shirt collar, "there is a dress in which to associate with gentlemen!" "True," replied Bob very quietly; "I don't dress very well, but if I had gone down to Snip's and run in debt for my clothes, I might have appeared as well as you do." This was a stunner, so to speak, and Bob was declared the winner by a full bench.

Both Witty & Wise

He was always ready with replies that had a salutary smart in them. Though an early and ardent Jackson man, in honor of whose inauguration he illumined his house from attic to cellar in 1829, and inheriting the Democratic chart in politics, he turned over to the free soil side of the question, for which he was abused by those with whom he had previously acted. About this time a movement was made against the banks of his State, and Bob, having a few shares of bank stock, took a decided stand in support of the banks, against his old associates. "Well, Bob," said one of these, "I hear you have gone over to the enemy. That's just the way; as soon as a man gets a dollar's worth of bank stock and a house to his back, off he goes among the aristocracy." Bob was all the time pursuing his work of grafting trees -- he is a famous grafter, and buds will grow if he but look at them -- and only stopped long enongh to to say: "Adze, if you paid less attention to politics and more to your business, you might pay off that mortgage on your house in a little while." Adze made no further remark.

Bob's idea of family discipline would hardly be adopted yet, though we are fast gaining on it. All great ideas have found the course slow before they are established. He has had a fine family of children, though they have become divided -- some here and there, and some yonder, beyond the reach of earthly care and sorrow. When they were young, he was asked the question if he ever flogged them. "Flogged them!" said he in a tone half indignant "no, that would be too cowardly, I am going to wait till they are big enough to strike me back, and then pitch in. It is mighty mean business to strike a child."

He has filled offices of trust and emolument, but has been more distinguished for those he didn't fill. He has been captain of an engine, fence-viewer, constable, and keeper of the court-house, the latter of which offices he now holds in connection with that of messenger to the Fire Department. He was invaluable on election days, before his town was divided into wards; and stationed by the polls, no man passed that he did not know -- that fact being regarded as prima facie and sufficient evidence that the unknown one had no right to vote. They might do away with the check list in the town and no inconvenience be experienced. How he does now, I don't know, but have no doubt that at the last election he exercised the same watchfulness over the ballot-box of his ward.

He is well posted in the news of the day, but living so far from Boston, he receives his paper but twice a week. Asking him how he liked this, he replied that he liked it very well, for he had found that news was like beef steak, much better after it had been kept a little while.

This little matter of personal biography may recall the individual to the memory of many. It is the story of a little life, rather than a large one, but it has been usefully and honorably spent. I know no stigma that attaches to his name. Odd, rough, abrupt, he proves in a thousand ways, that sterling stuff rests beneath the at times forbidding exterior of MY BROTHER BOB.

CONTINUE with MY BROTHER BOB

CHARACTER SKETCH OF BOB SHILLABER (continued)

Even More on Old Bob

When I published the first paper describing the peculiarities and idiosyncracies of My Brother Bob, there were those who said I had not given the world the best illustrations of his character--each one of them having some pet anecdote of his own that should have stood luminous in the foreground. There are indeed many such that might be told, and to present a few more features of a similar character I have been induced to venture this paper.

I believe I hinted in my previous sketch that Bob was meditating a suit against a railroad for damages in cutting off certain privileges. This he has actually commenced, and a vigorous fight he is making of it, with a certainty of winning if justice is at all regarded. The specifications in his claim are very funny. They are more savory than elegant, and I cannot use them here, but the close is a triumph of magnanimity and a number of other virtues. He says if the directors of the road will only come and endure for eighteen or twenty years what he has done--the villanous smells and noises and sights, the interrupted view by and the interrupted rest by night--and then refuse to him the modest amount he demands, he will pay it to them.

This, however, needs the choice strong words of Bob's vocabulary to give it due force. His rhetoric is unapproachable in its distinctness and point. While on the stand as a witness in this case, he was asked if there was not a mutual dislike betwixt him and some other party of the opposition. He said there was not. "Do you deny, sir," said the lawyer for the Road, "that there is a mutual dislike between you?" "I do," said Bob, "most decidedly; he has a dislike for me, but I hate him." I am sorry to record the fact, but the distinction is very nice, and I cannot omit the incident though it tell against him.

One of our most honored and respected naval officers asked me the other day if I was the brother of my Brother Bob, which was at once an introduction to a most delightful acquaintance. Bob had been his right hand man in beautifying and adorning his grounds, and if a plant by any chance didn't grow, it wasn't Bob's fault; Nature had to bear all the responsibility of the failure. But they rarely failed. There was such a thorough undestanding betwixt him and them that they seemed to make up their minds to flourish at once after he had looked at them. Like the housewife who was boiling soap and kept it from boiling over by the force of her will, saying it didn't dare to, so they didn't dare depart from the directions he gave them. There always seemed a trembling among the more sensitive of the vines when he went through them for fear that they had transgressed in some way. He is wonderful in grafting. Grapes from thorns and figs from thistle are no impossibilities with Bob.

At the commencement of the war when gold took its first start, Bob had some hundred dollars or so in gold pieces that he had put by for a rainy day. No one who knows him will accuse him of extravagant practices, and his economy has enabled him to secure a respectable pile, the gold being simply the dust that rolled off in the piling. He saw the rise one per cent.! two per cent.! three per cent.! "It must be down to-morrow," thought Bob, as he counted over the ingots, like the broker of Bogota. But no; the next day it was four, and Bob grew nervous. Then it was five--six--and, at seven, he could contain himself no longer, but put his yellow boys in the hands of Discount, the broker, who gave him seven dollars in green-backs on the hundred. The next day it leaped to ten and in a very short time it was up to fifty, at which time he told me the story of his want of shrewdness. There was one thing, however, to comfort him. As to every deep there is a lower deep, so if we but think that to every misery or disappointment there is a greater, we gain comfort and thank heaven it is no worse. So reckoned Bob. "Why," said he, with a tone of great satisfaction, "there were some ---- fools here that sold at four."

The idea of being outwitted pained him most. There is one man in his town whose shrewdness he holds in the highest respect. He marvels at the positive genius he shows in his operations. It is to ordinary shrewdness what the genius of Sherman is to common clodhoppers in the science of war. It was Bob's fortune to sell him some hay by the lot, at the shrewd man's own valuation, who a few days afterwards came to Bob with a long face, telling him that the hay fell short about one hundred pounds, and asked allowance for it. Bob told him he should make none. "Well," said the genius, "I will tell it, all round town, that you cheated me." "Do it," said Bob, "by all means; only let it get about that I was sharp enough to cheat you, and my fortune is made."

There is no man more loyal than my brother Bob. He has a bright eye on the conduct of the war, and criticises everything with the sharpest discrimination. No one is exempt from his strictures, were he a thousand times his friend. At a time of terrible inertness in the army, when active service seemed suspended forever, Bob was terribly exercised about it. He was engaged in his garden, and his spade went into the soil as if he were throwing up entrenchments. "Dead enough," said he, as he worked his spade by some obstacle; "dead enough; why, a defeat would be better than this." There were certain emphatic words interspersed that gave the sentence a gothic massiveness.

My Brother Bob comes to town but seldom, holding the city in but poor esteem. The sun rises here, as he avers, when he stops over long enough to prove it in the south west and sets he don't know where. He has never seen the great organ yet and says he don't want to, which is an offence not to be forgiven.His early musical education, however, was neglected, which may be submitted in palliation. When asked during a visit which he liked best, Boston or his own town, he replied gravely that he liked the latter best, because he could lie down there in the street and sleep with no danger of getting run over, while here he was in danger all the time with his eyes wide open.

I have written thus far and my pen cleaves to the subject, but I dare risk no more, at present. I received a letter from him yesterday, dated "Poverty Cottage, Highlands, Wibird's Hill" -- the location may be remembered by some--where Bob lives enjoying the otium cum dig., cultivating a potato patch and rendering himself useful for a consideration, taking care by a judicious advance in the value of his service to wake a depressed currency go as far as ever he did.

Text scanned courtesy of The Brewster Family Network

Copy of Rambles courtesy Peter E. Randall

History Hypertext project by SeacoastNH.com

This digital transcript © 1999 SeacoastNH.com