| Ranger Barely Captures HMS Drake |

JOHN PAUL JONES & PORTSMOUTH, NH

JOHN PAUL JONES & PORTSMOUTH, NH

Despite a mutinous Piscataqua crew, Paul Jones pulled off America's first major sea battle. The first successful American naval "raid" is all the more amazing, considering the odds against its success. Jones was fighting an enemy spirit within his own ranks from men more interested in plunder than democracy.

I got an email the other day from a man in France claiming that his ancestor had purchased HMS DRAKE from John Paul Jones. He still had the receipt from 1779. Jones' daring capture of the British warship Drake in its home waters by the RANGER, built here in Portsmouth Harbor, is among this nation's very few maritime victories from the American Revolution. And it was the reaction on shore by English citizens that helped turn the tide of war. The terrifying attack shocked English citizens into a new understanding of the American cause. But it is the battle on board the Ranger between the Scotsman Jones and his Piscataqua region crew that reveals the mood of the reluctant Continental Navy.

The truth is that Jones' New England crew had no stomach for battle. Most were not Yankee patriots, as they were later portrayed, fighting for liberty and democracy. They were privateers. Jones enticed local men aboard Ranger using handbills and a news article in the NH Gazette promising a quick profitable trip to Europe and back. They lacked their captain's passion for a glorious battle at sea. Whatever goods they could plunder with the least risk were fine with them. Grabbing a British merchant ship in familiar Atlantic waters was one thing, but taking on a fully-armored English warship 3,000 miles from home was, to their minds, lunacy.

Crew on the Edge of Mutiny

His own crew, not the enemy, foiled Jones' first two attempts to take the Drake. When the feisty captain proposed surprising the 20-gun Drake in broad daylight while she lay docked in Carrickfergus in Ireland, his sailors, speaking through Portsmouth lieutenant Thomas Simpson, simply refused to go. When Jones revised the plan into a nighttime assault, a drunken mate missed his command and botched the guerilla mission. Instead of grappling the two ships together for the surprise attack as planned, the Ranger missed its mark and anchored 100 feet from its quarry. A sudden shift in weather forced Jones to sail back out of the harbor, leaving the Drake still unaware and resting calmly in port.

His own crew, not the enemy, foiled Jones' first two attempts to take the Drake. When the feisty captain proposed surprising the 20-gun Drake in broad daylight while she lay docked in Carrickfergus in Ireland, his sailors, speaking through Portsmouth lieutenant Thomas Simpson, simply refused to go. When Jones revised the plan into a nighttime assault, a drunken mate missed his command and botched the guerilla mission. Instead of grappling the two ships together for the surprise attack as planned, the Ranger missed its mark and anchored 100 feet from its quarry. A sudden shift in weather forced Jones to sail back out of the harbor, leaving the Drake still unaware and resting calmly in port.

John Paul Jones' vision was three-fold. No British warship had ever been taken at home by Americans, so the Drake's crew might be exchanged for American prisoners of war held in British prisons. The prized ship could be sold to pacify the crew's desire for plunder. And the show of force might shock the British public into taking the American Revolution seriously. While other American captains were scarcely able to defend their own harbors, Jones was thinking outside the box.

Within hours of the Drake fiasco at Carrickfergus, Jones convinced his reluctant crew to stage a raid across the waters on the nearby port of Whitehaven, England, a town he knew well from his youth. They planned to kidnap the Earl of Selkirk there and hold him for ransom. The Earl, however, was not home and the raid inflicted little damage on the port. Still the "pirate" Jones became an instant celebrity for his bravado alone. His crew, unaware they were making history, conspired to sail off leaving Jones ashore. One man even alerted locals that the Americans were in town.

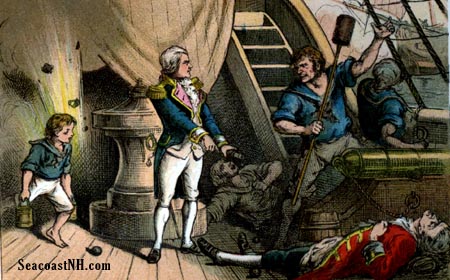

Things might have gone even worse. Piscataqua crewmen were so enraged by their rash, glory-seeking Captain that they mumbled about tossing Jones from the Ranger into the sea and returning to Portsmouth. Jones later wrote that he was nearly forced to shoot some of his mutinous men. Both sides backed down.

Our First Major Naval Victory

Back at Carrickfergus harbor after the Whitehaven raid Jones openly drew attention to the Ranger, still disguised as a British merchant ship. When Drake sent a small boat to investigate the suspicious ship, Jones welcomed the party aboard and captured them. This trickery apparently appeased the Piscataqua crew who helped their captain lure the Drake into open water, a cat-and-mouse chase that took an entire day. Then in the waning minutes of daylight, the Ranger attacked.

An hour and five minutes later, the battle was over. The enemy captain and his first lieutenant were mortally wounded. The Ranger boarding party had to step over the body of a British sailor. Blood mixed on deck with the burst contents of a barrel of port, brought on deck in anticipation of the Drake's victory party. Jones' wild plan and brilliant maneuvering won him the favor of his Yankee crew -- but not for long.

Word spread quickly and British ships were soon hot on the trail of Ranger. Towing the captured Drake with its 200 British prisoners, Jones eluded his pursuers by sailing north, then west around Ireland. Heading back to the safety of France, the Ranger spotted small prize ships en route. But when the Drake, under Captain Simpson, was cut loose so that Ranger could grab more prizes, the American captain disappeared in the fog and slipped away in the Drake.

Bad Times Back in France

The discord flared again. When the Drake arrived in France, Jones had Simpson confined to quarters, then held in a French prison ship and eventually in a French jail for disobeying orders. Simpson, a brother-in-law of Ranger owner John Langdon, explained that he had misunderstood Jones’ orders shouted from Ranger to Drake. Jones explained to his superiors that, anticipating trouble, he had given Simpson written orders to stick close by Ranger, no matter what happened.

While Jones partied in Paris, the Ranger crew languished aboard ship for three months. A majority of the Ranger’s "Jovial Tars" signed a protest letter, praising their fatherly leader Simpson, and damning Jones. The Scottish captain, they complained, had threatened to shoot crew members whom "in sallies of passion he chooses to call ignorant or disobedient". Simpson, it appears, even managed to turn French officers against Paul Jones by disseminating his view of the Drake battle in which he himself was the hero and not the traitor.

Jones, to his credit, was determined to stay "on message" and to return to worry the British with his guerilla – biographer Evan Thomas falls just short of using the word "terrorist" -- naval tactics. French ambassadors Benjamin Franklin and John Adams convinced Jones to let the Ranger return home to Portsmouth under Lieutenant Simpson. Following a disappointing year of inactivity, Jones finally took the revamped BONHOMME RICHARD back to Britain for its bloody victory against HMA SERAPIS. Jones proved that he could command a second major sea victory with a different ship and a different crew, and carved himself a top spot in American naval history. Simpson, who stayed on as commander of Ranger, later lost the ship to the British in South Carolina.

Despite their behavior, Jones sympathized with the Jovial Tars, blaming their actions on Simpson’s influence. Jones worked overtime to get them their reward for the captured prizes. When the impoverished American Congress did not come up with payments to the Ranger crew, Jones had to mortgage his captured prizes just to pay for their food. The Drake brought in only a small portion of its value and a year later was in the hands of a wealthy French merchant at the port of Nantes.

But the Piscataqua crew – angry, ill-equipped, and unpaid -- had already taken their small revenge. The Drake, Jones discovered, had been plundered. Even the uniforms of its British prisoners had been stolen by crewmen or sold. Jones’ personal effects stored aboard ship were tossed out and trashed. Jones biographer Lincoln Lorenz suggests that the "craven and disloyal" Piscataqua men formed the worst crew Jones commanded in his military career. Happy to see the last of Jones who stayed in France, the Jovial Tars quickly turned their protest against Thomas Simpson during the long voyage home.

Copyright © 2004 by J. Dennis Robinson. All rights reserved.

READ ALSO: Ranger Raids Britian

Sources: Jones biographies by Lincoln Lorenz (1943), Samuel Eliot Morison (1951), William Gilkerson (1976) and Evan Thomas (2003) and "John Paul Jones and the Ranger" editor by Joseph Sawtelle (1994).

Images from SeacoastNH Library: (top) Jones with Piscataqua crew from 1855 Harper's New Minthly Magazine, Dell conic panel from 1959 film, Jones aboard captured ship from Paul Jones by J. Ward, prior to 1891, (bottom) 1905 illustration by Helen Tilton.