| Two Men Who Tore Down Portsmouth |

HOW HISTORY HAPPENS

HOW HISTORY HAPPENS

One was a New Hampshire governor. The other ran a house of ill repute. Together they pushed the pendulum too far one way. People got angry. The pendulum swung back – and the Portsmouth preservation movement was born. But two historic houses were lost forever.

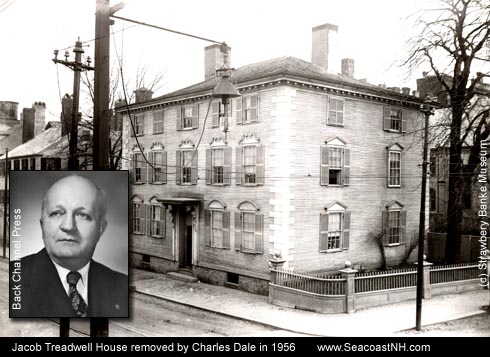

TREADWELL AND WENTWORTH MANSIONS LOST

Nothing fires the blood of preservationists like acts of wanton destruction. Despite the modern perception that Portsmouth is rich with historic houses, the fact is, most of the city’s great colonial mansions and first-period houses are gone. Only a precious few examples survive, and they survive, in part, because two men, both named Charles, roused the largely apathetic city to such anger that a few citizens finally took action. One was a Portsmouth mayor and New Hampshire governor. The other owned a whorehouse.

Charles H. "Cappy" Stewart and Charles M. Dale hailed from very different worlds, but among the many Portsmouth buildings they demolished in the name of profit and progress, two stand out. Stewart purchased the 1695-era home of Lt. Gov. John Wentworth for $3,500, sold off parts of it in 1926 and demolished the rest. Dale owned the Jacob Treadwell mansion, a sister to the stately Moffatt-Ladd House. After razing the historic building to the ground in 1957, he replaced it with a squat, flat-topped, modern bowling alley, now a restaurant and office suites at 1 Middle Street. Because both men and both buildings were well known, the loss of these two structures helped local historians rally support for a movement that saved dozens more buildings from the wrecking ball beginning in the 1950s. Had these two men not pushed the panic button, Portsmouth might not be the city it is today.

Cappy Stewart is best known as the owner of one of more of the "houses of ill repute" that lined Water Street (now Marcy). Little is know about the sex trade in Portsmouth at the turn of the century because few arrests were made under the protective eye of the local police. Most operated on the surface as legitimate hotels, dance halls, oyster bars, even an ice cream shop. By the turn of the 20th century, visiting "liberty parties" of as many as fifteen hundred sailors from military and merchant ships in Portsmouth Harbor appeared on the Portsmouth shore in a single evening. Before the construction of the Memorial Bridge from Kittery in 1923, most young men, some as young as fourteen, took the ferry from Kittery to the landing at the base of State Street. Their first sight, after as much as a year aboard a cramped all-male ship, was the glitzy bordello called The Gloucester House run by Mary Baker at the corner of State and Water streets. One Portsmouth resident, who saw the place as a child, says the bordello had mirrored ceilings, red velvet curtains, paintings of naked women and lots of little "cubby holes" around a grand ballroom.

After as many as a dozen bordellos were closed by the city in 1912, Cappy Stewart went from selling young girls to selling old houses and antiques. He kept a waterfront shop in the old Shaw and Sheafe warehouse buildings now in Prescott Park, back when this was a rough and tumble seaport. Stewart discovered he could turn a tidy profit by selling off carved panels, doors and other architectural details of stately Piscataqua homes. Built in the 1700s by wealthy merchants, Portsmouth’s old mansions were slowly deteriorating. In the 1920s, to preserve architectural traditions, The Metropolitan Museum in New York City was looking for classic examples of early architectural details to display in its American Wing. The "Met" considered buying portions of the Wentworth-Gardner House in the South End and what is now the John Paul Jones House on State Street. Both, however, were saved by preservationists. The John Wentworth House was not so lucky. The Metropolitan purchased an exquisite paneled room and the staircase from Cappy Stewart and other portions went to the Winterthur Museum in Delaware. Photographs from 1926 show one of the city’s important early structures being disassembled beam by beam. The house, once situated on Puddle Dock, was the birthplace of Benning Wentworth, one of the last royal governors of New Hampshire before the American Revolution.

Locals reacted in 1926 with a confused mix of pride and sadness. Although proud that a house from Portsmouth was considered valuable enough to include in an important museum, this sturdy building had long been an key landmark in local history. Suddenly it was gone forever.

More significant colonial buildings fell as the 20th century continued – the Jaffrey, Manning, Atkinson, Meserve, Storer, Boyd, Haven and Woodbury Langdon homes, just to name a few. Then for reasons not fully known, former Portsmouth mayor Charles Dale elected to destroy the Jacob Treadwell mansion (also called the Cutter-Langdon house) and replace it with a strip mall and bowling alley. Congress Street, the main road leading into the heart of the city, was still known as King Street when Charles and Mary Treadwell built the imposing structure for their son Jacob around 1765. Standing at the very top of Middle Street, it marked the turning point for every arriving visitor, from George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette to the Russian and Japanese delegates who negotiated the Treaty of Portsmouth in 1905. Encircled by an elegant wooden fence, filled with exquisitely designed rooms, the Treadwell was a fixture of the city until the spring of 1956 when workmen began tearing it down by Dale’s decree.

Charles Dale was not a Portsmouth local by birth. He was raised in Minnesota and North Dakota. Although already a lawyer, Dale enlisted in the US Army Coast Artillery Corps in World War I and was stationed at Portsmouth. He married Marion Marvin, the mayor’s daughter and was himself mayor by 1926. He reportedly earned a million dollar fee as attorney for the Prescott sisters, Josephine and Mary, who used their inherited money to buy up and tear down most of the "blighted" buildings in the former waterfront combat zone – creating Prescott Park. Dale went on to be a three-term New Hampshire governor from 1944 to 1949.

Although he did help preserve a few buildings, Dale’s "progressive" approach led him to favor new structures over old. He was strongly opposed to the Strawbery Banke preservation project in Puddle Dock and did his best to quash the creation of the museum there. Saving 27 old buildings in Puddle Dock, Dale said in 1958, was "a pig in a poke". Restoring so many structures to museum quality, he warned, would cost more than Portsmouth locals could afford to spend. Yet, ironically, it was the destruction of the Treadwell Mansion late in 1956 that convinced Portsmouth locals to rally together to create a preservation organization in 1958. Hundreds of residents gathered at the Rockingham Hotel, just a block from the flattened Treadwell House and listened to speakers protest the ruination of a once-great seaport. Without its grand historic homes, historians warned, Portsmouth was on its way to becoming "Anytown, USA".

The destruction of architecturally significant structures in Portsmouth did not stop after the creation of Strawbery Banke Inc. on November 18, 1957. But with the city more attentive to historic preservation, it became increasingly difficult for redevelopers to destroy old buildings without attracting public attention.

"In past days," editor Ray Brighton wrote on the front page of the Portsmouth Herald in November 1961, "if a business needed room to expand, it simply bought adjacent properties, regardless of their history, and brought in the wreckers to remove the old structures. But that’s not the rule here anymore."

The preservation movement had begun. In the 1970s, under Portsmouth City Planner Robert Thoresen, Portsmouth’s Market Square got a make-over, designed specifically to recapture the historic character and attract outside visitors. Re-animated historic buildings on the waterfront and downtown and in the West End helped draw a wave of young artists, musicians, restaurateurs, performers and entrepreneurs who helped turn the city into a cultural center that today attracts millions of tourists. Tourism, in turn, has become the key economic driver in the city and in the state of New Hampshire. And to be honest, we owe it all, in a strange way, to two men who pushed just hard enough to spark a revolution.

Photo sources: Treadwell Mansion and Cappy Stewart courtesy Strawbery Banke Museum. Lt. Gov John Wentworth House courtesy Richard Candee. Gov. Charles Dale courtesy of Back Channel Press.

Copyright © 2007 by J. Dennis Robinson. All rights reserved. Portsmouth of this article are excerpted from Robinson’s upcoming book on the history of Strawbery Banke Museum to be published late in the year by Peter E. Randall.