|

FRESH STUFF DAILY |

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

SEE ALL SIGNED BOOKS by J. Dennis Robinson click here |

||

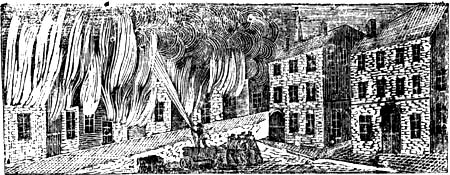

READ: Poem about 1813 Fire On Wednesday morning December 24, 1806, the second great downtown fire moved in from the Bow Street area, up Market Street and back toward the barely recovered square. On Wednesday December 22, 1813, the third and worst fire took out 300 buildings along State Street, flattening the city like a bomb blast -- from where the stone Unitarian Church stands today all the way to the Piscataqua River and out to the tip of the pier there. Blizzards, Yellow Fever, trade embargoes and the British War of 1812 combined with the three crippling fires were almost more than the city could bear. Merchants who had been burned out of Market Street and moved to the thriving State Street area were burned out there too. Many quit their professions, while others quit the city. Among them, the promising young NH attorney Daniel Webster, who lost his Portsmouth house to the fire of 1813, relocated to nearby Massachusetts.

Fire feasts on wood, and until that time Market Square was a maze of one and two-story timber-frame buildings linked by dirt roads half the width we know them today. People kept barns, stored hay, used candles and oil lamps, burned wood, cooked in their greasy fireplaces up creosote-choked chimneys. The threat of fire was constantly with them in ways we can only imagine. We have extensive records of earlier fires – a home torched by Indians here, a barn lost from a stray cinder there – but it wasn’t until the population began to grow and settle and shop in a central congested area, that such catastrophe was possible. And it wasn’t until the city had gone to ashes three times that influential (read "wealthy") townsmen were able to bring about the "brick laws" that forbade the building of tall wooden structures downtown. In this way, revolutionary and colonial Portsmouth changed into its industrial-strength red brick era. So our "ancient" town is relatively new – all the tall brick buildings we know downtown are from 1813 or later. Even the three main church buildings are newer and the brick St. John’s Chapel by the river is a replacement for the wooden one burned in Christmas 1806. Only wisps of the city that burned remain, and for that reason we have lost touch with the architecture of the poor and common people. Mostly, the distant homes of the rich remain with their wide protective lawns. But tear off that awful marquee above the former Eagle Photo building and you will see one of the oldest surviving wooden buildings downtown. The little alley between it and the rebuilt North Church would have been a main thoroughfare when Paul Revere stopped by in 1774. Multiply that little building all over town, remove the brick, the lights, throw in hay carts and muddy streets and you begin to see old Portsmouth before the great Christmas fires. City fire "fighting" was a different battle then. Despite expensive "pumpers", leather bucket brigades and the ultra-modern Portsmouth aqueduct, these three winter infernos were unbeatable. From the mid-1700s, those who could afford to, were members of Portsmouth "fire societies" at least two of which survive today in symbolic social groups. Surprisingly, the main task of early volunteers was not to battle Nature as much as to recoup their member’s worldly goods. Society members carried "bed keys" used to dissemble the valuable family bed for hasty removal. They wore black bags to carry off dishes and silver which they would protect from vandals. They carried mops, presumably to clean up afterwards. Despite the odds, they fought. An early newspaper report marveled at how the women of Portsmouth did not flee in the face of the 1802 fire, but pitched in and worked on the bucket brigades until they dropped from sheer exhaustion. Volunteers from nearby towns were instrumental in spelling the spent firefighters and in guarding valuables from the dozens of reported looters who many locals believed were themselves the arsonists or "incendiaries" as they were called back then.

There are stories of charity. After the 1802 fire contributions came from around the country for those who had lost their homes and shops. A reproduction of the account book is in the files of the Portsmouth Athenaeum. All told, their gifts, combined with local donations came to $45,410.43. Damage was estimated then at $200,000 for the loss of nearly 200 buildings. Large sums were donated in 1806 and 1813 as well. There are stories of treachery. One philanthropist, who rushed to contribute $2,000 had his pocket cut away and his money stolen by thieves on his way to the donation site. Newspapers played on the theme of arson and one local poem even prayed, in rhyme, that those villains -- not punished by law -- would by punished by God. There are stories of valor too. In 1813 volunteers from Newburyport, Dover, Exeter, Durham and surrounding towns saw the city in flames and came running, some bringing their own "engines". Commander Isaac Hull, formerly commander of "Old Ironsides" and newly installed at the Navy Yard, sent his shipyard firemen. According to Nathaniel Adams’ "Annals" a group of 40 men arrived all the way from Salem, having traveled 48 miles in six hours to relieve the fatigued locals. One man from Newburyport rushed into a burning building and rescued a crying child. But in all the tales of the Portsmouth Christmas fires, in article after article and account after account, in three destructive days over more than a decade -- with over 500 buildings destroyed – we could find no record of a single death. Not one, and that is the true miracle of the three Portsmouth Christmas fires. READ: More Portsmouth Fires, 1846

TOP PHOTO: Detail from photograph by Aaron Rohde Originally published (c) 1999. Revised 2005 by J. Dennis Robinson. All rights reserved. Click for Update Sidebar

Portsmouth historian Joyce Volk tells us that fear of theft, not fire, appears to have been the driving force behind the creation of Portsmouth’s early fire societies. Wealthy citizens like Wyseman Claggett and James Stoodley lost items in a 1761 fire, the same year the first fire society was founded here. As many as six groups were formed with up to 25 men in each. Numbers were kept small because members of each group were shown where their comrades kept their most valuable items. Members of the Federal Society, for example, knew a secret password that allowed them inside member houses to salvage valuable items when fire threatened. Others stood guard over items once removed from the house. "It seems to me pretty clear that this was their motivating force, "Volk says. "Some people were decent., others were not. These were 25 men who trusted each other." Volk has researched the formation of the Portsmouth fire societies and published her findings in two history periodicals available at the Portsmouth Public Library. The creation of private fire clubs began well before the three famous fires that struck the city in the early 1800s. Homes were required to have numbered leather fire buckets that could be used by volunteers to carry water. Two of those 18th century buckets, Volk says, were sold a few years ago at auction for $45,000 each. Two of the early societies, the Federal and Mechanics group, still exist, Volk says, as social clubs. --- JDR Please visit these SeacoastNH.com ad partners.

News about Portsmouth from Fosters.com |

| Tuesday, April 23, 2024 |

|

Copyright ® 1996-2020 SeacoastNH.com. All rights reserved. Privacy Statement

Site maintained by ad-cetera graphics

HISTORY

HISTORY