| The Shot Not Heard Round the World |

230 YEARS AGO THIS MONTH

Did the American Revolution really start at Fort William and Mary in New Hampshire? Local historians like to think so. Historian J. Dennis Robinson takes one more shot at the story that just misses the major history texts, but looms large in the life of the Seacoast.

READ: More on Fort Constitution Raid

Four months before "the shot heard round the world" in 1775, Portsmouth held its own little Revolution. On December 14, 1774, four hundred local citizens surrounded the king’s military base at nearby New Castle, overpowered the soldiers there, hauled down the British colors, shouted "huzzah" and made off with nearly 100 kegs of gunpowder. The following day hundreds more locals returned to steal muskets and disable the cannons. New Hampshire’s royal governor John Wentworth, his wife Frances and their son were later forced to flee the Port City for Canada.

Why the raid on Fort William and Mary does not echo through the halls of American history still mystifies locals. The brazen attack and overthrow of the British military base here was a key link in the chain of the American Revolution. King George of England, according to one 19th century scholar, was so embittered by the Portsmouth attack that it made war with the Colonies inevitable. But the raid was apparently not bloody or violent enough for the textbooks. Nor did it take place in Massachusetts, Virginia or Philadelphia where tradition tells us, the nation was born. Tradition, perhaps, but the facts say otherwise.

Why the raid on Fort William and Mary does not echo through the halls of American history still mystifies locals. The brazen attack and overthrow of the British military base here was a key link in the chain of the American Revolution. King George of England, according to one 19th century scholar, was so embittered by the Portsmouth attack that it made war with the Colonies inevitable. But the raid was apparently not bloody or violent enough for the textbooks. Nor did it take place in Massachusetts, Virginia or Philadelphia where tradition tells us, the nation was born. Tradition, perhaps, but the facts say otherwise.

It certainly was not the first overt act of the Revolution. Colonists in each province, angry over the Stamp Act and other taxes had been scuffling with British forces for a decade by this time. Portsmouth’s official stamp tax collector George Meserve, for example, had been burned in effigy and forced to resign back in 1765. The Liberty Pole still standing across from Strawbery Banke Museum is a testament to that insurrection. Rhode Islanders seized a number of boats from the King’s navy and peacefully removed supplies from a fort there prior to the raid at William and Mary.

The famous Boston Tea Party had taken place one full year earlier, although the event was more political theater, and much quieter, than history implies. In a copycat response to the hated British tea tax, Portsmouth protesters took a stronger stand. Rather than disguise themselves as Indians and discreetly dispose of a shipment of tea, rebels here set ablaze one entire ship and its costly cargo.

The distinction of the Portsmouth raid on Fort William and Mary is that it was the first fully organized, large-scale, armed attack on the authority of the King himself, local historians argue. While Colonial militia at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts later defended themselves against British aggression, the citizens in seacoast New Hampshire were in open revolt. Paul Revere himself spurred the crowd to action after making an earlier, but much less famous, ride from Boston to Portsmouth. He told the local Committee of Safety about the recent insurrection in Rhode Island and warned that the British ship Scarborough was on its way with troops to fortify the king’s stronghold at New Castle. Colonials, according to a new law, would not be allowed access to munitions or buy weapons exported from England.

By leading this spontaneous little revolution, New Hampshire merchant John Langdon of Portsmouth and lawyer John Sullivan of Durham were committing treason, punishable by death. Governor John Wentworth, a native of Portsmouth, certainly knew who the leaders were. He mentioned Sullivan in his letters, but never revealed Langdon to the King. After the Revolution, both Langdon and Sullivan became governors of the state of New Hampshire.

By leading this spontaneous little revolution, New Hampshire merchant John Langdon of Portsmouth and lawyer John Sullivan of Durham were committing treason, punishable by death. Governor John Wentworth, a native of Portsmouth, certainly knew who the leaders were. He mentioned Sullivan in his letters, but never revealed Langdon to the King. After the Revolution, both Langdon and Sullivan became governors of the state of New Hampshire.

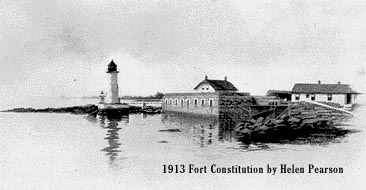

New Castle is an island of just one square mile. Today it is New Hampshire’s smallest town, but it looms large in Granite State history. In the 1600s "Great Island" was the provincial capital and the fort there was among the earliest British defenses in the New World. The brick structures standing there today, adjacent to New Hampshire’s only mainland lighthouse, date from the 1800s. Historians are not sure exactly how Fort William and Mary looked at the time of the raid in 1774. In Revolutionary days, the lighthouse was made of wood. Still it must have been a startling scene as hundreds of rag tag farmers, merchants and mariners arrived on the chilly shores in scores of small boats.

Shots were fired, but not loud enough to arouse the men who wrote the ballads and the histories of the American Revolution. Although Gov. Wentworth, aware of the rising passions of his citizenry, had requested additional troops from his superiors, only six men guarded the fort on December 14. Captain John Cochran, commander of the tiny group, recorded his version of the attack in a report to Gov. Wentworth.

I told them on their peril not to enter. They replied they would. I immediately ordered three four pounders to be fired on them, and then the small arms; and, before we could be ready to fire again, we were stormed on all quarters, and they immediately secured both me and my men, and kept us prisoners about one hour and a half, during which time they broke open the powder-house, and took all the powder away, except one barrel ; and having put it into boats and sent it off, they released me from confinement. To which I can only add, that I did all in my power to defend the fort, but all my efforts could not avail against so great a number.

Ironically, New Hampshire’s Governor Wentworth was much more sensitive to the patriot cause than were royal leaders in Massachusetts. Born in Portsmouth, a classmate of future president John Adams at Harvard, Wentworth was generally well-liked, and a critic of harsh British tariffs. He did raise eyebrows in town when he married his cousin Frances Atkinson just ten days after the death of her first husband.

But more than most Loyalists, Wentworth saw the handwriting on the wall. In his view, New Hampshire citizens did not want a rebellion. Portsmouth depended on trade with England. He lay the blame squarely on Paul Revere, who had alarmed the locals with false rumors of coming British troops, he said, and turned the citizenry into an armed mob. Although it was "a most unhappy affair", Wentworth guessed correctly that punishing the rebel leaders and military reprisals would only make matters worse.

A week after the raid, John Wentworth wrote this to a friend in England:

No jail would hold them long and no jury would find them guilty; for, by the false alarm that has been raised throughout the country, it is considered by the weak and ignorant, who have the rule in these times, an act of self preservation.

The British ship Scarborough with its British soldiers eventually did arrive as Paul Revere had warned to reclaim the New Castle fort. Gov. Wentworth and his family were forced to stay aboard the ship for safety. Eventually he was appointed governor of Nova Scotia at Halifax where his mansion is still in use by the latest British minister to the region.

Legend says that the gunpowder stolen from Fort William and Mary made its way to Breed's and Bunker Hill, where more New Hampshire men served than militia from any other state -- another fact all but lost to history. Renamed Fort Constitution, the structure was renovated for the war of 1812 and again in the Civil War. The bloodiest day in New Castle occurred at the fort, strangely, on the Fourth of July in 1809. While preparing for an Independence Day celebration, soldiers planning a patriotic cannon salute left damp ammunition drying in the sun. Set off by an errant spark, the explosion killed nine men. A severed limb reportedly crashed through the window of a home nearby.

The fort was abandoned in 1890 and is minimally maintained by the state of New Hampshire today. There are no exhibits and no tour guides to tell the story of the state’s most important military battle. Only a few signs remind us of the raid that so clearly told King George that the colonists in America were fighting back. Visitors are left to wander the 19th century ruins located near the New Castle Coast Guard station. John Wentworth’s wooden lighthouse, built to his instructions in 1771, has long since been rebuilt. The current lighthouse is a large cast iron cone, now painted white, that stands over the crumbling ruins. In 1775, the light from the New Castle tower was John Wentworth’s final view of his hometown as he sailed off beyond the Isles of Shoals, never to return.

Originally published May 22, 1999 by SeacoastNH.com. Revised and updated (c) 2005 by J. Dennis Robinson. All rights reserved.

MUCH MORE on the Fort at PortsmouthForts.com

SEE ALSO: New Castle Lighthouse Tour

CLICK Ahead to see supersized illustration of Fort William & Mary

UNDATED SKETCH OF FORT WILLIAM & MARY

The current Fort Constitution was rebuilt a number of times and little remains of the original "Castle William and Mary." This is an unknown artist's interpretation of the early fort and lighthouse which was rebuilt by British Gov. John Wentworth and raided by Seacoast, New Hampshire "patriots" following the first ride of Paul Revere in 1774. One expert says the lighthouse here is on the wrong side of the fort. This image was taken from a photo owned by the late Joe Copley who prepared a bicentennial booklet on the fort in 1974. He said the picture was discovered "behind a picture being reframed in 1894." The location of the original drawing is unknown.

(c) SeacoastNH.com