|

FRESH STUFF DAILY |

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

SEE ALL SIGNED BOOKS by J. Dennis Robinson click here |

||

Page 1 of 2

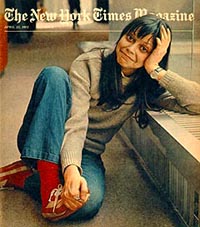

Brilliant and hard-drinking UNH literature professor Max Maynard never achieved the fame he craved. His daughter Joyce, however, landed on the cover of the New York Times Magazine at age 18. In 1973, as one family career shot skyward, the other fell like a stone.

The first time I saw New York Times writer Joyce Maynard, she was bouncing on her bed. I saw her through a second-story window. It wasn't my fault. I was painting her family’s house.

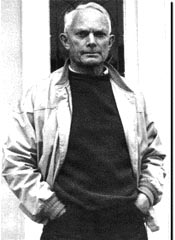

Max was an amazing and tortured man. He was short and often grim. His face and body seemed chiseled from stone and he walked erect like a Roman statue set loose from its pedestal. When he smiled it was more of a grimace. His face squeezed together like Edward G. Robinson, he squinted, and his lower lip, pink and wet, curled downward. He did not look pleased then, but he was. Max’s lectures on literature, to my mind, were raptures on the past, a past he seemed to know intimately. When he spoke of Cicero or Samuel Johnson, it was as if he had just returned from lunch with him. He drew masterful sketches on the chalkboard as he spoke and erased them. Max was a phenomenal teacher and an avowed heavy drinker. When I painted his house in the summer of my junior year, he would greet me in the garden, half in the bag, a glass of vodka in each hand. We drank and talked and talked and drank. He never got beyond the rank of assistant professor. If you asked Max what he loved, he said he was really a painter. His house was filled with unsold landscapes. Born in India in 1903, he had lived and painted in Canada before World War II and was an associate of Emily Carr who is beloved in Victoria and British Columbia. Commercial fame eluded him. His Cubist-style images, drawn from his Calvinist heritage, won him few accolades outside of western Canada. My life, he told me wistfully, was just unfolding. His was nearly over.

I graduated from college the following year and when Max learned that I was taking summer courses at Oxford in England, he gave me his address. He too was escaping to England. He was 70. His teaching career was over. His marriage was over too. His wife Fredelle, a successful magazine editor at Redbook and 20 years his junior had finally thrown in the towel. She was also publishing a new book. Their daughter Joyce was publishing her first bestseller that year. Max, who craved fame almost as much as vodka, was in hell, but he stood like a statue as we spoke, curled his lower lip and shook my hand farewell. When my Oxford course ended, I had two weeks to spare before returning to New Hampshire. I took a bus to Max's place in East Grinstead, England. Again the warm handshake and the curled lip. He was staying in a large rented country house with a garden and chicken pen. We drank vodka and he told me about his days as a cowboy, his childhood in Western Canada, his painting. We compared lives – his seven decades and my two. We drank more. Finally, he talked of his daughter Joyce, now tabloid-famous for her relationship with Salinger. Max was morose, fearful for his daughter amid instant fame, lost in his own lifelong quest for recognition. He was painting again and his paintings filled the rented house. "We were meant to work our way up slowly," he told me referring again to Joyce, "Not that fast." He searched in the sink for two clean plates among the piles of dirty dishware. We ate vegetables fresh from the English garden. He made an omelet from the eggs we found in the borrowed hen house. He refreshed our drinks. He led me out to a wooded area behind the house and pointed out the "Pooh tree" where writer A. A. Milne’s son Christopher used to play. "I want to visit her," he said at last, "but she won't have me. I would give up everything, even my painting, and fly back there in a minute. I'd move in and simply tutor her, help her take all this success slowly." Just before Max fell, he took my hand in his. He had confessed, moments before, that he loved Joyce. "I don't want to see her fall from grace," he said. "I don't want to see her hurt." CONTINUE "The Day Max Fell"

Please visit these SeacoastNH.com ad partners.

News about Portsmouth from Fosters.com |

| Friday, April 19, 2024 |

|

Copyright ® 1996-2020 SeacoastNH.com. All rights reserved. Privacy Statement

Site maintained by ad-cetera graphics

HISTORY

HISTORY

Stop me if you think I'm on thin ice here, but this story has been eating at

me for more than 30 years. It isn't about Joyce, really, but about her father

Max Maynard who was my professor at the University of New Hampshire.

Stop me if you think I'm on thin ice here, but this story has been eating at

me for more than 30 years. It isn't about Joyce, really, but about her father

Max Maynard who was my professor at the University of New Hampshire.  Joyce must have been back from her first and only year at Yale when I saw her

accidentally through her bedroom window in 1972. At age 18 she looked 12. A couple

of months earlier she had blown us all away with a cover story in the New York

Times Magazine. She was the sudden darling of the post-Boomer generation. Even

reclusive JD Salinger, the New Hampshire author of "Catcher in the Rye" wrote

to praise her. Months later, Joyce moved in with the 53-year old novelist. Her

father was enraged, broken hearted and even a bit jealous. Salinger was the same

age he had been when Joyce was born.

Joyce must have been back from her first and only year at Yale when I saw her

accidentally through her bedroom window in 1972. At age 18 she looked 12. A couple

of months earlier she had blown us all away with a cover story in the New York

Times Magazine. She was the sudden darling of the post-Boomer generation. Even

reclusive JD Salinger, the New Hampshire author of "Catcher in the Rye" wrote

to praise her. Months later, Joyce moved in with the 53-year old novelist. Her

father was enraged, broken hearted and even a bit jealous. Salinger was the same

age he had been when Joyce was born.