| The Day Lincoln Died for Me |

Abraham Lincoln has a number of ties to Seacoast, NH. But Lincoln has ties to everywhere. Sometimes you just have to go to where history happened. No historic site in America, none is more powerful than the bedroom in the Peterson House in Washington DC. In April 1865 Lincoln was carried here from Ford’s Theater across the street. Today, it looks exactly the same.

For all our pretensions to being an historic region, when push comes to shove, our Seacoast still plays in the minor leagues. There's never been a textbook battle here, no truly famous son or daughter, no world-renowned natural disaster, no earth-shattering discovery. We've had our fair share of tragedy and triumph -- shipwrecks, fires, colonial uprisings, homecomings and celebrity visits. Ben Franklin installed a lightning rod. Paul Revere delivered a message. Washington slept here. We repeat these familiar local stories like a sacred mantra.

Don't get me wrong; that's not a bad thing. Our relative obscurity has acted as a sort of preservative, coating the region with what passes for an historic varnish that is centuries thick. Our collective memory is strong, and each generation paints another thin protective coating. That's the main reason people visit here today. Compared to most historic destinations, this place is practically untarnished.

Who cares if none of the three world leaders actually showed up for the Treaty of Portsmouth in 1905? Who's counting when 400 local men defeated an army of only six British soldiers at Fort William and Mary? So what if the most famous guest at Wentworth-by-the-Sea was President Eisenhower's brother Milton? It's our history, durn it, and that's all that matters.

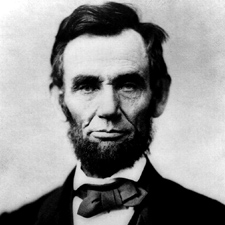

Abraham Lincoln died in mid April, and this was going to be a column about Abraham Lincoln's connections to the Seacoast, and unlikely as it may seem, there are plenty. I'm not just talking about Lucy Hale of Dover again, fiancé to John Wilkes Booth who assassinated the President. There was also Lincoln's campaign trips to the Seacoast, the ones some say built his New England popularity that eventually won him the election. He used the trips as an excuse to see his son Robert Todd, who was then a student at Phillips Exeter Academy here.

I might have written pages about the Isles of Shoals link to Wilkes' brother actor Edwin Booth, but I didn’t. Edwin Booth, according to Ripley, once saved Robert Todd Lincoln from stepping in front of a speeding train. I was going to tell you about the Lincoln saddle in a glass case on the third floor of the Woodman Institute in Dover, or the Lincoln House were Todd visited with his dad in Exeter.

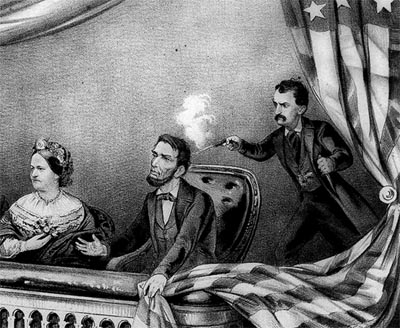

No, sometimes even a diehard cowboy has to get out of Dodge to take his bearings, and so not too long ago I found myself standing at the foot of the bed where Abraham Lincoln died. You probably toured the famous Peterson House in Washington, DC with your fourth grade class. I was sick and missed that field trip by about forty years. But I know the story like my own name. I know that the first doctor on the scene did not know why Lincoln lay slumped and silent in his rocking chair at Ford’s Theater until his finger slipped into the tiny bullet hole at the back of the President’s head. I’ve read book after book on the assassination, so that it plays out in my mind like a long slow motion film. I can see Lincoln being carried across the street from the theater to this 10-by-15 foot boardinghouse room, the assassin's .44 caliber bullet still lodged in his brain just above the eye.

Continue with LINCOLN ASSASSINATION

Continue Abraham Lincoln Assassination

It took nine hours for the powerful frame of the President to give up its battle, the final battle of the long horrific Civil War. Doctors worked to remove blood clots from the wound and the medical debate about whether Lincoln could have been saved rages on uselessly to this day. Booth's derringer is in the basement museum of Ford's Theater across the street. The hunting knife is there too, the one Booth used to slice open the arm of Major Rathbone who just happened to be sitting with the President and his wife in the balcony box on April 14, 1865. The bullet, some hair, and a fragment of the poor president's skull, I understand, along with the doctor's blood-stained shirt cuffs are on display at Walter Reed Army Medical Center just down the road in Washington, DC.

Tourists still file into the Peterson House from the street in an endless parade as they have from the first hours after the body was removed. Back then they were less orderly. Julius Elke, a boarder at Peterson's took a fuzzy photograph of the bloody bed where the president had lain, placed diagonally to accommodate his lengthy frame. Then the souvenir hunters swarmed in, grabbing up everything in sight - clothes, bedding, furniture, even shredding bits of wallpaper and carpeting.

Today visitors still climb a few steps and turn into a dark hallway of the Peterson House where a young US National Park ranger with a walkie-talkie smiles and directs the flow of traffic to the left, through the parlor where Mary Todd Lincoln screamed and cried uncontrollably at the news of her husband's death. Visitors file through another small room which, for a few short moments, served as the seat of the US Government as the mantel of leadership passed on. Booth had intended to cripple the North by assassinating the vice president and secretary of state as well, but his rag-tag troupe of conspirators failed by inches.

Had I been in fourth grade like the 21st century kids who pushed past me in line, shoving their way from the boring old parlor and into the death bed room, things might have been different for me. "Where's the blood?" one wanted to know. "Are those his real boots?" another asked. But maybe nothing changes. They stopped, like I did, mouths hanging just a little open and there was a silence in that room. It hung forever, like the sound of a coward's derringer held inches from a great man's skull. It ended in a second, like it must a thousand times a day there at the Peterson House.

Like everyone, I snapped the obligatory photos of an empty wood-poster bed. It looks for all the world like the one in Julius Elke's picture - same spread, same striped wallpaper. There are at least three famous paintings of the deathbed scene I know, and in each the room grows larger. Like history, the room expanded to accommodate all the lesser known faces that mingled aimlessly at the edge of importance.

I know it isn't the real pillow, but I touched it just the same. Don't ask me why. I wasn't in that room a full minute before the clot of pilgrims washed me out the door, down a stairway, along a long hall and back into the street. To the left a life-sized cardboard figure of George W. Bush smiled from the doorway of the Souvenir Factory. Past T-shirt booths to my right (3 for $10) the red neon sign of the Lincoln House Bar and Grille popped my catatonia. I was back in America.

Unlike most tourists, I did Ford's Theatre second, snapped my obligatory picture of the assassination scene and gaped even further at the relics in the basement. They have the door in a glass case there, the one Booth rigged with a peep hole and a stick, so that he could enter silently unseen. Booth was a great actor remember, and knew Ford's Theatre well, better even than history buffs like me. There was, as I had long hoped, the carte d' vise of Lucy Hale, the pictures of her and four other women Booth had in his pocket when he was shot in the spine at Garrison's barn twelve days later. I saw the authentic white hoods worn by the conspirators when they were hung months later in an explosion of anger following the war and the death of their newly sainted President.

From Ford's I hopped a trolley to the Lincoln Memorial. After seeing Lincoln so mortal, I needed that giant statue there to pump his memory back to its impossible proportions. I watched for half an hour as one tiny person after another stood, staring up at the Colossus of Illinois, the barefoot boy from the log cabin who became a minor god. It was impossible not to be moved. It was impossible not to compare the greatness of one president to the mediocrity of so many others.

Portsmouth has no such holy place, where someone so towering was laid so low. We offer a kinder gentler perspective on American history. We can sense it daily in small doses just walking through the city streets. But sometimes you have to stand where it all happened. We need to measure our lives against such national deities. And I did. I stood at the edge of Lincoln’s bed like a bug-eyed fourth grader. I heard, for myself, the total silence that followed the president’s final breath and passed through the empty air where greatness disappeared.

Copyright © 2006 by J. Dennis Robinson. All rights reserved.