| Save the Seal, Keep the Ship |

NH Legislators should study up

before trashing Seacoast history

There is a move afoot in Concord to alter the state seal and to erase New Hampshire's revolutionary history and its seacoast origins. A proposed bill threatens to remove the image of a tall ship from the seal and replace it with the profile of the former Old Man in the Mountains.

It is a nice sentiment, but a bad idea. We all miss the craggy Old Man who tumbled to his death in Franconia Notch last year. Perhaps we took him too much for granite. But to now deface the historic state seal in memory of an optical illusion would be to forget how the Granite State really came to be.

New Hampshire was born, not in the majestic White Mountains, but at the sea. An outpost of coastal fishermen, fur traders and timber merchants evolved into one of the nation's first important shipbuilding centers. New Hampshire was already 150 years old in 1775 when Portsmouth citizens drove British governor John Wentworth out of town. That very year, six months before the appearance of the Declaration of Independence, independent New Hampshire adopted an official seal. That seal -- honoring the origins of the state -- showed a fish, a tree and a quiver of arrows. Five arrows represented the early seacoast settlements along the Piscataqua. A Latin phrase printed around the outside of the seal read "In Unity There is Strength".

The state seal has seen only one major change since. In 1784, capitalizing on the state’s growing shipbuilding trade, the NH legislators adapted the seal to show, instead, a wooden ship under construction or "on the stocks" and a rising sun. Over the next century and a half engravers interpreted the design. A pair of "unofficial" human figures and tiny wooden barrels – some say rum barrels -- appeared, disappeared, and reappeared in versions of the seal. The flag on the ship shifted and seemed to change direction in the wind. In 1909 the seal was added to the design of the New Hampshire state flag.

The state seal has seen only one major change since. In 1784, capitalizing on the state’s growing shipbuilding trade, the NH legislators adapted the seal to show, instead, a wooden ship under construction or "on the stocks" and a rising sun. Over the next century and a half engravers interpreted the design. A pair of "unofficial" human figures and tiny wooden barrels – some say rum barrels -- appeared, disappeared, and reappeared in versions of the seal. The flag on the ship shifted and seemed to change direction in the wind. In 1909 the seal was added to the design of the New Hampshire state flag.

In 1931 Governor John Winant, a former St. Paul's School teacher, appointed a special commission to crack down on unauthorized imagery. The committee understood its mission well. "We early came to the conclusion," they reported, "that no material change in the device of the seal was expected or would be desirable." Instead of re-inventing history, the group drew up a detailed standardized description of the official seal, including the angle of the ship, the direction of the fluttering flags and the percentage of sun on the horizon. Loose barrels and random human figures were banned, but one item was added. The seal now included "a granite boulder on the dexter side" of the ship. The boulder was to symbolize the solidity of the Granite State and the solidarity of its citizens. So in one small sense, the Old Man of the Mountain is already depicted – in spirit anyway.

In 1931 Governor John Winant, a former St. Paul's School teacher, appointed a special commission to crack down on unauthorized imagery. The committee understood its mission well. "We early came to the conclusion," they reported, "that no material change in the device of the seal was expected or would be desirable." Instead of re-inventing history, the group drew up a detailed standardized description of the official seal, including the angle of the ship, the direction of the fluttering flags and the percentage of sun on the horizon. Loose barrels and random human figures were banned, but one item was added. The seal now included "a granite boulder on the dexter side" of the ship. The boulder was to symbolize the solidity of the Granite State and the solidarity of its citizens. So in one small sense, the Old Man of the Mountain is already depicted – in spirit anyway.

Now for the first time the generic tall ship got a name. The image was to officially represent the Frigate Raleigh, built at Portsmouth in 1776. It may be just a coincidence that the USS Constitution or "Old Ironsides", the most famous surviving ship in American history, visited Portsmouth in 1931. Ironsides had spent almost two decades in Portsmouth Harbor in the late 1800s, but was returned to its home port of Charleston, Massachusetts. New Hampshire had no ship as famous as Ironsides, but it had a ship that was built much earlier.

Looking for a famous Portsmouth-built ship from the Revolution, according to state records, a researcher noted mention of the Raleigh in a 1917 copy of National Geographic. According to the article, the Raleigh was the first ship to carry the new American flag into battle at sea. Historians dispute the claim, and ironically, John Paul Jones is largely credited today with taking the first "stars and stripes" to Europe in another Portsmouth ship, the Ranger.

Rally Round the Raleigh

Historians know a lot about the Raleigh. Thomas Thompson, the ship's first captain, kept a scrupulous log. We know that most of the men aboard for the maiden voyage to France were, like Thompson, from Portsmouth. We know what the ship carried for stores and armor. We know almost exactly what the Raleigh looked like too because it was later captured by the British during the Revolution and the British took very accurate measurements of their prize. These records became the guidelines for the artwork on the 1931 seal.

The Raleigh was among the very first ships built for the tiny Continental Navy. Even during its production the builders in the six coastal colonies raced to see which could get its ship into the water first. Amazingly, the skilled New Hampshire craftsmen built the large man-of-war in just 60 days. The New Hampshire Gazette was on hand to cover the spectacular moment in 1776.

On Tuesday the 21 st (of May) the Continental frigate of 32 guns built at this place under the direction of John Langdon, Esq., was launched amidst the acclaim of many thousand spectators. She is estimated by all those that are judges that have seen her to be one of the complesatest ships every built in America. …this noble fabrick was completely to her anchors in the main channel, in less than six minutes from the time she run, without the least hurt; and what is truly remarkable, not a single person met with the least accident in launching, tho’ nearly five hundred men were employed in and around her when run off..

Building the ship was one thing. Finding arms and a willing crew proved much more difficult. It was August 12, 1777 before Thompson could get his cannon delivered from Connecticut and finally get underway. His mission, along with the ship Alfred (made famous earlier by John Paul Jones ), was to pick up military supplies at France. Thompson captured a few small prizes along the way, but here the Raleigh story begins to darken.

Returning from France, the Alfred and the Raleigh spotted a British convoy. They teased out a small ship for the kill and then battled a British man of war. But when the Alfred was cornered, rather than fight on, Thompson chose to get his valuable military supplies back to the Colonies. Criticized severely for this decision, Thompson lost his ship to John Barry, considered by many to be the true "Father of the American Navy" over John Paul Jones. But only two days out of Boston in 1778, Barry lost the Raleigh to two very powerful British ships off Wooden Ball Island in Maine. Barry escaped. Two dozen men were killed. The Raleigh, which Barry had hoped to destroy, was seized by the enemy.

The British loved their new prize. The Raleigh, built by innovative Yankee hands, was a high-tech ship compared to the lumbering vessels in the Royal Navy. Ironically, as the American Revolution raged, the Raleigh was used to capture another Portsmouth-built ship – the one New Hampshire ship that certainly has earned more fame than its sister. Off Charleston, South Carolina, the British-manned Raleigh captured the Ranger. John Paul Jones had just recently captained the Ranger from Portsmouth in a hugely successful one-ship raid on the British coast. Ranger was, in essence, a smaller, sleeker version of the Raleigh itself, designed on the same lines by the same Portsmouth workers. After being used to carry American prisoners of war, the Raleigh was decommissioned in July 1781 at, amazingly, Portsmouth, England.

Candy is Dandy, but Liquor is Quicker

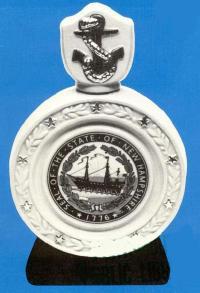

The decision to designate the ship on the state seal as the Raleigh was scarcely known in the 1930s. The results of the governor’s special commission were forgotten as the state turned its attention to the Great Depression. It wasn’t until the Revolutionary Bicentennial celebrations of 1976 that the report became public. Someone suggested that the colorful state seal would make a classy souvenir when turned into a liquor decanter.

Costas Tentas, Chairman of the state Liquor Commission agreed. So did NH Governor Meldrim Thompson, Jr.. Thompson was especially pleased, he wrote Tentas in 1975, to learn that the history of "our handsome State Seal" was to be distributed in pamphlet form to school children in the Granite State. The pamphlet, prominently showing a photograph of the liquor decanter on its cover, was paid for by Mr. Boston Distillers. The state government proudly shipped off copies to teachers, children and libraries around the state. It is from that pamphlet, written by state legislative historian Leon Anderson, that much of this information is drawn. Anderson created similar booklets for commemorative liquor decanters of the Cog Railway, General John Stark and Hannah Dustin, heroine of 1697 massacre of Indian captors. It was through the sale of alcohol that New Hampshire passed its heritage on to its children.

Old Ship or Old Man?

In his detailed history of the NH seal, historian Anderson went to great length to demonstrate the importance of the frigate Ranger. One of its crewmen, Hopley Yeaton, was a founder of the Coast Guard, he says. Thomas Thompson’s house still stands in Portsmouth next to the mansion of John Langdon, who got one of the first lucrative ship building contracts from the Continental Congress, on which he also served. The two men are still neighbors in the historic Portsmouth North Cemetery.

But that’s not really the point. The ship on the bottle of booze is not actually the Raleigh. It could represent the Ranger. It could represent any number of sturdy sailing ships built along the Piscataqua around the time of the Revolution. History suggests that New Hampshire was building important ships here as early as 1690. We have built sleek schooners, stunning clippers, grand whalers, sturdy gundalows, atomic submarines, great side-wheelers, steamships, yachts, dories, frigates, sloops, ketches, yawls – you name it. New Hampshire and Maine workers built the Kearsage, the Congress, the Portsmouth and the America.

We did not build the Old Man of the Mountains. First recognized by Native Americans, the Old Man was not officially "discovered" by white men until 1805 when the Granite State was nearly 200 years old. Until it fell, the Old Stone Face represented the immutability of Nature. Nature, it turns out, is not immutable. So what will the Old Man symbolize to future children who never saw it?

And then there is the tradition of the state seals themselves. All the seals of the 13 original colonies tell stories of the nation’s founding and the Revolution. All that is, except Maine, that did not become a state until 1820. Many show symbols of our early economy or European origins. None of the seals have been replaced in modern times. Vermont, after updating its seal, changed back to its original design in 1937. A state seal is about how we got started,

If it ain’t broken, as we Yankees say, don’t fix it. The question is not how to memorialize the Old Man. We can do that on commemorative quarters and T-shirts and pennants and tablecloths and postcards galore. The real question is -- Why can’t we remember how America got started? The story – for now – is right there on the seal. This nation – and this state -- started at sea level, and then worked its way up.