| Frederick Douglass Comes to Town |

SEACOAST BLACK HISTORY

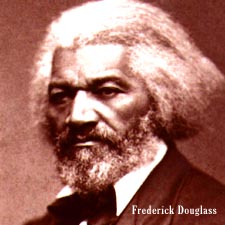

Born a slave, he became the most famous Black man in America and advisor to Abraham Lincoln. Even as the Civil War raged Frederick Douglass visited Portsmouth and lectured on the future of black Americans. His two sons were soldiers. And he remembered his first inhopistable visit to the Granite State too.

VISIT our NH Black History section

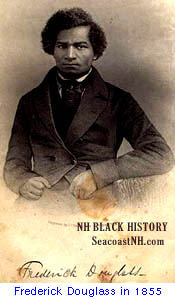

In the final version of his autobiography, published not long before his death in 1895, Frederick Douglass recalled an early visit to New Hampshire. This story takes place in 1842 when Douglass was just 25 years old. Twenty-one of those years had been spent as a slave. He bore on his back the marks of the lash, he likely told his white audience in Pittsfield, NH, during his fiery abolitionist lectures. They did not want to know the horrible details of slavery, he would say, and then he would tell them details all the same.

"I’m afraid you do not understand the awful character of these lashes" Douglass said politely. Then he proceeded to explain how an enslaved man could be stripped naked, tied to a tree or post and lashed with a knotted whip almost to the bone for the smallest of infractions. He recited chapter and verse from American laws that allowed slaves to be lashed for riding a horse without permission, for selling goods without permission, for gathering in groups of more than seven without permission, for walking off the main roads. Slaves, by law, could have an ear removed or be branded with the initials of the "man-stealer" who owned them.

"I’m afraid you do not understand the awful character of these lashes" Douglass said politely. Then he proceeded to explain how an enslaved man could be stripped naked, tied to a tree or post and lashed with a knotted whip almost to the bone for the smallest of infractions. He recited chapter and verse from American laws that allowed slaves to be lashed for riding a horse without permission, for selling goods without permission, for gathering in groups of more than seven without permission, for walking off the main roads. Slaves, by law, could have an ear removed or be branded with the initials of the "man-stealer" who owned them.

Over 3,000,000 slaves in that era were forbidden to marry. As he spoke to the Pittsfield audience gathered at the local church in 1842, Douglass himself was, even then, still a fugitive and a slave. He had escaped his Maryland owner to marry a free black woman named Anne Murray. He often told of an enslaved couple who, with their children, were sold to separate farms. When the man asked to say farewell to his family, permission was denied. When he moved out of raw emotion to embrace them, he was beaten and killed in their presence. Another black man, Douglass related, who struck his owner in self defense was killed, decapitated and his head displayed as a warning to others. A woman who taught her child to read was hanged. There were 71 crimes for which a black could be executed, three for a white. This was the law of the nation where he lived.

Educated in "the school of slavery", Frederick Douglass carried these lessons to the little New Hampshire town, sent by the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society to teach the truth at their Sunday meeting.

His New Hampshire sponsors, the Hilles, greeted the dusty black traveler coolly, Douglass reported. The master of the house, oddly, was unable to attend dinner with his guest. The next morning, when Mr. Hilles picked up his wife in their carriage, he did not offer the empty seat to Frederick Douglass who walked the two miles to the church alone, then lectured to those assembled. Mr. Hille was unable to attend. During a break in the service, no one spoke to Douglass. At lunch, again, no one spoke to him or offered him lunch. When he found a small hotel nearby, the invited lecturer was told "they did not entertain niggers there." Cold, hungry and despondent, Douglass says, he went and sat in a small cemetery. Death, he said, seemed to be the only barrier to discrimination. New Hampshire’s image of itself as an early open-minded northern haven for blacks is largely wishful thinking. New Hampshire’s only native-born President, Franklin Pierce, signed the Fugitive Slave Act into law, then extended the bounds of US slavery Westward.

We can only hope Douglass met with a warmer reception two years later in 1844 when he first lectured in Portsmouth. There is no mention of the visit in local newspapers, just a notation in the orator's extensive travel logs. A year later Douglass' first explosive autobiography was in print. In it, he named his Maryland owner, thus targeting himself as a fugitive. In 1846 he fled to the United Kingdom where he lectured continuously, shedding light on the true nature of what he called "American Slavery."

" The slaveholders want total darkness on the subject," he told enthusiastic British audiences. " Expose slavery and it dies. Light is to slavery as to what the heat of the sun is to the root of the tree."

Douglass devoted his life to exposing slavery and agitating for equality for blacks, through his lectures, his books and as editor of two abolitionist newspapers. Mockery, harassment, threats of death did not slow his mission.

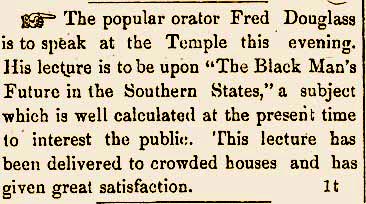

America was in the thick of its gruesome Civil War when Douglass returned to Portsmouth on March 15, 1862. Like so many abolitionists before, white and black, Douglass spoke this time at the 1,000 seat Portsmouth Lyceum, known as "The Temple" on the site of today’s Portsmouth Music Hall. By now Douglass was a freed man, well known for fiery impassioned rhetoric and as publisher of the North Star. He was a confidant of President Abraham Lincoln, who often wavered on his convictions toward emancipation, fearing the impact of civil rights on the wounded nation.

Douglass advocated the use of black soldiers in the war. A year after his Portsmouth appearance, he became a recruiter for the now-famous 54th Massachusetts Regiment for blacks, while two of his own sons served in the bloody conflict.

This time the local papers trumpeted Douglass’ arrival. A display ad in the Portsmouth Daily Morning Chronicle announced the evening lecture by "The Eloquent Champion of Freedom". In order that everyone could attend, the admission fee was lowered to ten cents. A special notice elsewhere in the paper urged all citizens to attend this very important lecture and predicted a full house.

We have no report of exactly what Douglass said in Portsmouth, only the rambling and disquieting reactions of Morning Chronicle columnist "Uncle Toby". In the March 17 edition, "U.T." quotes scripture to suggest that the Bible was written by God for white readers only. The bible continually relates whiteness and light to piety and perfection, he says, and darkness to evil. "The way of the wicked is as darkness" Uncle Toby quotes, making a literal connection between skin color and the human soul.

Uncle Toby, actually a local minister and newspaper owner, reminds us that even northern churches were divided over issues of slavery and the future of black Americans after the Civil War. The North Church, for example, tottered back and forth on the issue, depending upon the whims of the preacher. Churches across the nation split into factions and Douglass did not shrink from verbal attacks on those Christians who sympathized with southern slave holders.

Elsewhere in the Chronicle, the editor points out that Uncle Toby’s comments were "written mainly for a joke" with no offense intended, and that the columnist "don’t fear a black future for anybody."

Joke or not, this 1862 discussion flirts with the very heart and soul of what Douglass called American Slavery, an immoral and flawed economic policy that evolved into the deep-seated racism that still afflicts the country today. Slavery, like indentured servitude, Douglass reminded his audiences, was initially about cheap labor. Many nations and races have practiced slavery. But in America, as the nation evolved, successful businessmen became increasingly addicted to slavery. They could not stay powerful and wealthy without it, they thought, and the nation’s laws -- though advocating freedom for all -- allowed even the trafficking of slaves, largely Africans, just as the country was being formed. As the prosperity and the nation grew, the addiction spread. Seacoast, New Hampshire, where great fortunes were made in the Triangle Trade and later in the cotton industry, was hooked as well. As the American image of slavery melted into images of the black race, our great national shame was forged.

The fact that many of these powerful businessmen were also the founders of our nation added a haunting legitimacy to slavery. Washington and Jefferson who owned a total of 500 men, women and children between them, wrestled with the problem. Washington freed all his slaves on his death. Jefferson, however, rationalized his position by searching for flaws within the black race itself. They were, he wrote, like children in need of protective parents. Like "Uncle Toby" hiding behind his Bible in Portsmouth, Jefferson needed a rationale for his racism. Like abusive partners, these otherwise kind and intelligent white men searched for reasons to explain their behavior within the character of their victims.

Jefferson freed only eight of his slaves and died deeply in debt, after which most of his "children" were separated and sold as human property to satisfy his creditors.

Frederick Douglass was the nemesis of these apologists and anathema to all their reasoning. He was clearly not in need of protection or guidance by whites. He was intellectual, cultured, religious, a former slave, yet financially stable and powerfully influential. The son of an unknown white father and an enslaved black mother, Douglass was able to walk a complex path in a white universe without abandoning his African heritage. It was a highwire act that demanded respect from people who saw and heard him. And so, Douglass spent most of his adult life allowing people, black and white, male and female, to see and to hear him. He traveled extensively in a world that often barred him from riding in public vehicles or appearing in public places. He worked with dignity among people who supported Negro rights, but would not dine with them. He could converse with abolitionists John Brown and Harriet Tubman, debate a southern slave-holder, address black prisoners in Washington, DC or captivate a British audience at tea.

A century after the Civil War, workers at Pease Air Force Base were still being offered housing off a separate list from the one shown to whites. The nearby Rockingham Hotel, just 10 feet from the Portsmouth Music Hall site where Douglass had spoken, offered segregated dining until 1948. A Portsmouth barber in the 1950s still told African American customers that he did not have "the right tools" to cut black hair. In the year 2000, that barber was still joking openly about the way he had turned away black customers. Old racism dies hard, even here in the liberal North. It gets into the DNA of a society, hides there, sometimes skipping a generation, waiting for the right set of conditions in which to reappear.

Douglass went on to hold a number of federal posts including US Marshall to the District of Columbia and a US emissary to Haiti and Santa Domingo. His large comfortable home in Anacostia, DC is today a national shrine. His visit to The Temple in Portsmouth in 1862, along with lectures there by other black abolitionists, has earned the site an honored place on the evolving Portsmouth Black History Trail. This is a place where a great man stood, the trail guide tells us, and where a bright light shone on the roots of racism. This is a place worth remembering.

Copyright © 2002 by J. Dennis Robinson. Updated 2005. All rights reserved. For more information read BLACK PORTSMOUTH, by Mark Sammons and Valerie Cunningham.