| Blood on the Snow in Portsmouth |

BOYS WILL BE BOYS

Every city has its turf wars. Young boys especially like to stake out their territory. Two winter battles, based in Portsmouth, have been immortalized in 19th century novels. One focuses on the bloody snowball fight on Slatter’s Hill. The second is about a death defying sled race down Mason’s Hill. Both speak volumes about being a boy.

Long before the winter Olympics, Portsmouth, New hampshire played host to a pair of cold weather games that still shiver in the annals of American literature. The famous snowball fight on Slatter’s Hill was perhaps more war than sport.

The fictionalized battle in The Story of a Bad Boy by Thomas Bailey Aldrich (1836-1907) is drawn from the author’s childhood experiences here in the early 1850s. The fight between the North Enders and the South Enders, Aldrich says, was based on a "mortal hatred" that had gone on between Portsmouth boys for centuries. The origin of the neighborhood rivalry was unknown, but traces of it still survive today among local natives.

The fictionalized battle in The Story of a Bad Boy by Thomas Bailey Aldrich (1836-1907) is drawn from the author’s childhood experiences here in the early 1850s. The fight between the North Enders and the South Enders, Aldrich says, was based on a "mortal hatred" that had gone on between Portsmouth boys for centuries. The origin of the neighborhood rivalry was unknown, but traces of it still survive today among local natives.

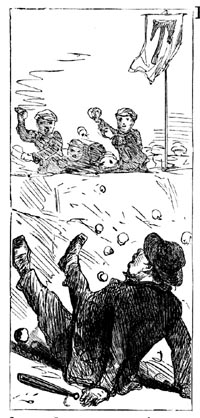

In his famous 1869 novel, Aldrich describes the battle with military precision and even includes a detailed sketch of the snow fort and its armory. One afternoon, the story goes, twenty or thirty North-enders took control of the fort on a rise of ground called No-Man’s Land. The walls were four feet high and twenty-two inches thick. Each gunner was equipped with a sizeable pyramid of perfectly-shaped snowballs. Projectiles containing rocks or made of ice had been banned by agreement of the opposing generals. A make-shift hospital was in place and a detention area set aside for captured prisoners. By 2 pm a force of fifty Puddledock boys or "River-Rats" were poised for the attack.

Continue BLOOD ON THE SNOW

BOYS BEHAVING BADLY (continued)

Aldrich’s novel, reprinted in scores of editions, is still in print today. That is not true of another Portsmouth winter boy battle. The adventures of The Double Runner Club by Benjamin Penhallow Shillaber (1814-1892) are now largely forgotten. Born in Portsmouth, Shillaber went on to become one of the best known American humorists of the nineteenth century. In 1848, two decades before Aldrich published his classic adventure book for boys, Shillaber invented Ike Partington, whose major function, initially, was to plague his aunt, Mrs. Ruth Partington, a comic character reportedly based on the author’s own aunt from Portsmouth. Shillaber left the Seacoast at age 18 to become a journalist and publisher in Boston, but always felt a deep connection to Portsmouth.

Over the next thirty years, Shillaber slowly developed the mischievous Ike in his newspaper columns that were collected into books. But Shillaber was in his sixties, nostalgic for his youthful days in Portsmouth, before he finally fleshed out young Ike Partington. His three adventure novels for boys, published between 1878 and 1882, are filled with intriguing memories of life along the Seacoast in the early 1800s.

Over the next thirty years, Shillaber slowly developed the mischievous Ike in his newspaper columns that were collected into books. But Shillaber was in his sixties, nostalgic for his youthful days in Portsmouth, before he finally fleshed out young Ike Partington. His three adventure novels for boys, published between 1878 and 1882, are filled with intriguing memories of life along the Seacoast in the early 1800s.

The Double Runner Club, last in the Ike Partington series, opens with a death-defying race down Mason’s Hill, the steepest slope in Rivertown, Shillaber’s fictional name for Portsmouth. (Aldrich typically refers to the city as "Rivermouth"). This time, it is the Corner Boys who are dead set against the Downtowners, but the historic rivalry is the same. But when a tough kid named Si Fairbanks arrives from Boston with a top-notch sled nicknamed "The Flyer", he easily defeats the local boys.

The only way to out race the big-city kid, Ike and his friends decide, is to build a double-runner sled. Raising a dollar, they convince Mr. Dennett, the carpenter, and Mr. Fernald, the blacksmith, to build the machine. Carrying six boys, the double-runner handily defeats Si and the Flyer, but hurtles toward the waters of the mill pond. Later Ike and his cronies accept a challenge from the boys of nearby Tatnic. They win again, but lose control of the massive double-runner and plow through the door of a local farm house, tearing up the threshold and the kitchen floor.

Tom Bailey and Ike Partington are bad little boys. Tom, Aldrich’s alter ego, manages to shoot an arrow into a friend’s mouth while playing William Tell. He sets a wooden carriage on fire in the middle of Market Square and knocks himself unconscious with a stash of stolen gunpowder. Ike frequently lies, occasionally steals, disrupts school and cruelly dispatches a cat.

Tom Bailey and Ike Partington are bad little boys. Tom, Aldrich’s alter ego, manages to shoot an arrow into a friend’s mouth while playing William Tell. He sets a wooden carriage on fire in the middle of Market Square and knocks himself unconscious with a stash of stolen gunpowder. Ike frequently lies, occasionally steals, disrupts school and cruelly dispatches a cat.

Shillaber, who earns a footnote in American literature as one of the nation’s earliest comic writers, never matched the fluid and exciting writing style of Aldrich’s Story of a Bad Boy. Critics note that Shillaber’s juvenile fiction often falls into the trap of describing events, rather than dramatizing them. But Shillaber biographer John Q. Reed suggests that BP deserves extra credit for promoting the renaissance in children’s adventure literature in the nineteenth century. His early contribution to the rise of "boy books" paved the way for Mark Twain’s adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. Twain acknowledged his debt to both Portsmouth authors.

Before BP Shillaber, American books for children were highly didactic and moralistic, populated by dull, squeaky-clean characters that exemplified perfect little boys and girls. The Peter Parley and Little Rollo series of the early 1800s taught children to be thrifty, polite, obedient, industrious, careful and well groomed. Shillaber despised these so-called "Sunday School" books and satirized them in his newspaper writing. Good parents, he chided, should whip their children regularly. Shilliber’s hero Ike Partington, who first appeared in print when Thomas Bailey Aldrich himself was only a boy, was a rebel with a distinct cause. By designing Ike as both devilish and unapologetic, Shillaber paved the way for adventure books that children could identify with and read with enthusiasm.

In fact, Shillaber developed his own theory of adolescent behavior that plays well even today. Ike Partington, Shillaber once wrote, was designed specifically as "an imitation of the universal human boy". Real boys, the author argued, naturally do bad things and should be allowed to experiment and work out their mischievous nature, rather than be molded too early into well-mannered adults. In the introduction to Lively Boys! Lively Boys!, first in the Ike Partington series, Shillaber expounds:

"The Boy must not be judged by the standard of Childhood or Manhood. He has a sphere of his own; and all of his mischief, frolic, and general deucedness, belongs to his own condition. The Boy has but little plan, purpose, or intention, in what he does, beyond having a good time. Boys that think, and have no interest in the doings of boyhood, may be delightful aids to a quiet home; but the life, spirit, energy, and health of the active Boy, comes with his activity."

The corollary of the "human boy" axiom, Shillaber implies, is that the adult male is no more responsible for his actions as a boy, than the butterfly is for the destructiveness of the caterpillar it once was. Boyhood, in essence, is a free pass with no strings attached. There are no juvenile delinquents in Shillaber’s world, just more boys.

Continue BLOOD ON THE SNOW

BOYS BEHAVING BADLY (continued)

There is, possibly, a message here for modern parents who tend to regulate their children’s lives with the precision of a railroad timetable. Boys, Shillaber implied, have a good heart and an inner virtue that will – or in some cases, will not – find its way to the surface, irregardless of the meddling of grown-ups. Shillaber critic John Reed says the Portsmouth-born writer believed "it is better for them to grow up free and naturally than to attempt to make them miniature adults".

Shillaber’s "human boy" is, of course, always in danger of not growing up at all. Later in The Double Runner Club, two Portsmouth urchins hijack a boat from the wharf for a joyride and, after losing an oar, are carried down the Piscataqua River and into the sea. They sail all-night and, arriving on a foreign shore, knock at the door of a lighthouse keeper. When a woman answers the door, the boys say they have come "From America" and ask if she speaks English. She does. They have landed at the Isles of Shoals, ten miles out. When the boy is returned to his parents in Rivertown the next day, the lighthouse keeper asks them if they were afraid their lost boy had drowned. Not likely, the boy’s parents say, "for one born to be hanged, couldn’t be drowned."

Meanwhile, back at Slatter’s Hill, Portsmouth’s North-Ender gang finally lost the fort after a week-long siege. To regain control from the dreaded Puddledockers, Aldrich’s bad boys were forced to use heavier ammunition – snowballs filled with buckshot, rocks and marbles, then dipped in water and frozen.

Matters grew worse and worse, Aldrich writes. With more and more injured boys, the selectmen of Rivermouth voted to stop the bloody battle and sent a posse of policemen. The attack of the adults forced the surviving boys from both neighborhoods into the fort where they became allies against a common enemy. The police charged again, but could not get within ten feet of the fort before they were repelled. When one adult managed to reach the fort, Aldrich writes, "he was seized by twenty pairs of hands, and dragged inside the breastwork, where fifteen boys sat down on him to keep him quiet."

In the end the adults won. They always do. Time is immutable. Boys grow up. But boys, as Shillaber and Aldrich knew, do not become men easily. The process is a messy one. it took all eight officers of the Portsmouth police force and a number of volunteers to take the fort which was then razed by order of the town council.

But the winter legends of Portsmouth live on, tenuously, in literature. To their dying day, Aldrich writes, the old boys of Portsmouth were heard to say -- "By golly! You ought to have been at the fights on Slatter's Hill!".

Copyright (c) 2004 by J. Dennis Robinson. All rights reserved.