| Why John Smith Never Returned |

THE LOST NEW ENGLAND COLONY

After Jamestown and Pocahontas, Captain John Smith traveled along the American East Coast and coined the phrase "New England". He planned and almost pulled off a colony here. New Hampshire historians like to believe that Smith was headed back to the Piscataqua region or nearby when his colonial plans fell to pieces. Here is the story as we know it so far.

SEE: Photo History of Smith Monument in NH

John Smith tried to start a colony here

In history as in horseshoes "close" doesn't count. Still, now and then, someone tries so terribly hard to change the world, that it seems he should win an honorable mention. Take, for example, Captain John Smith, the man who gave New England its name. Long before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth, Smith vowed he would start a colony here and he almost pulled it off. But failures, history insists, are doomed to a Purgatory of scholarly footnotes. Here is what happened to Smith's failed New England colony:

Our story – the New England colony that failed – begins as Smith leaves Jamestown. In 1610, wounded and half-dead, Captain John Smith lay huddled below decks of a ship bound from Jamestown Colony back to England. After three years in the New World, his short term as "president" of America's first permanent settlement was already over. He would never see Virginia again, but by 1610 Smith had already carved one future notch in US history textbooks.

He had already saved the fledgling colony, explored the Potomac River, and had his famous encounter with Native American "princess" Pocahontas. While in Virginia, always prone to speaking his mind despite the consequences, Smith was thrown into prison, sentenced to death by Jamestown leaders and nearly killed in multiple Indian attacks.

He had already saved the fledgling colony, explored the Potomac River, and had his famous encounter with Native American "princess" Pocahontas. While in Virginia, always prone to speaking his mind despite the consequences, Smith was thrown into prison, sentenced to death by Jamestown leaders and nearly killed in multiple Indian attacks.

Even before Virginia, John Smith had been a soldier of fortune in the Mediterranean, then fought in a "holy" Christian crusade in Transylvania. There, according to his autobiography, he killed three Turkish warriors in single combat, lopping off their heads, which he displayed on pikes. Smith was wounded, captured, sold into slavery, freed by Princess Charatza Tragabigzanda, then was tossed into another prison by her brother. This time he escaped by murdering his captor with a cudgel and traveling, penniless and on foot through Russia and Poland, where he was wounded, to finally rejoin his troops.

After his bloody Crusade, Smith returned to England via Africa, got bored, signed on for Virginia and made his mark on American history. That brings us right back to 1610 when we find Smith, at the ripe old age of 29, still battling the severe burns he received in an explosion at Jamestown. He had been done in, not by a ferocious enemy, but by the spark from a comrade's tobacco pipe that ignited Smith's gunpowder bag as he slept. Impoverished again, unable even to walk Smith languished two months at sea, then lay months longer in a cheap London room, depressed, seeing no one but the doctor who came each day to dress his wounds.

CONTINUE to read the CAPTAIN JOHN SMITH

The Failed New England Colony (continued)

A hard man to kill, Smith recovered. His book "A True Relation" about the first years of Jamestown made him the toast of literary London. His honesty and radical ideas, however, frustrated the rich and famous who were investing heavily in the New World experiment. The corporate "money men" were looking to get rich quick. Like the Spanish in South America, they wanted gold. Smith had searched hard, found no gold, and said so. Smith advocated a slower return on investment through farming and trading with the Natives. Investors saw the independent-minded military man as a threat and tried to sabotage the publication of his second book, "The Proceedings of the English Colony in Virginia." Smith got the book out, and it rocketed up the bestseller charts.

Despite his fame, dressed in fox fur and armor, Smith was out of place in civilized London. He was dying for another adventure, and to prove that his ideas on colonization were the best. In his absence, Jamestown had all but fallen to bits when about 500 colonists died of starvation, some even turned to cannibalism. Radical or not, Smith's ideas were starting to make sense.

Despite his fame, dressed in fox fur and armor, Smith was out of place in civilized London. He was dying for another adventure, and to prove that his ideas on colonization were the best. In his absence, Jamestown had all but fallen to bits when about 500 colonists died of starvation, some even turned to cannibalism. Radical or not, Smith's ideas were starting to make sense.

Here Smith turned his sights on uncharted "Northern Virginia" which at that time stretched into modern day Canada. His strategy was simple. Though he promised investors he would search for gold and jewels, Smith quietly equipped his two ships, The Frances and The Queen Anne, with fishing and whaling gear. With a hand-picked low-budget skeleton crew, Smith was off to America and back within six short months, but the impact of his trip continues to this day.

Although Smith found no gold, he brought back a motherlode of furs, dried fish and fish oil. Investors were jubilant. In one short trip they were able to buy both ships, pay off the small crew, give Smith a tidy sum and still they had 8,000 British pounds in profit. While his men had been fishing the cod rich banks of "New England" as he named the area, Smith had sailed from Nova Scotia to Rhode Island in a small portable boat. His sketch became the first accurate map of New England - the map that would ultimately lead Europeans in droves to a brave new world.

Now comes the point in this tale where history makes less sense than what almost happened. Captain John Smith was suddenly the hottest investment in London, and Smith wanted to return to New England to found a permanent colony. Unlike in Virginia, Smith's New England colonists would be tough, skilled and quickly self-supporting. They would not waste their time hunting for gold, but would fish, hunt whales, trap for fur and cut the abundant timber. They would work with, not against the native tribes. This was a long term, low-risk proposition, Smith explained. Smith had scouted a number of ideal spots including Monhegan Island in Maine, others near modern day Boston and Plymouth, Massachusetts, and an area now called Portsmouth, New Hampshire near the Isles of Shoals, which he named "Smith Isles" after himself.

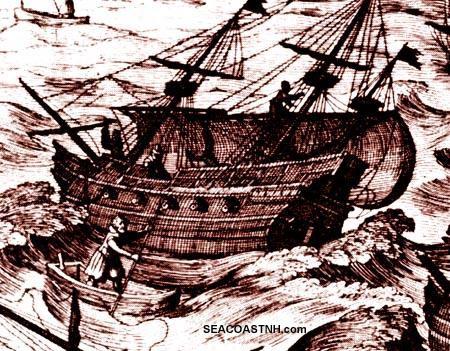

In 1615 Smith set sail, fully equipped, with his team of supercolonists, determined to start the first permanent colony in New England. It was over in days. Within 400 miles of England the two ships were ravaged by a killer storm, and by the time they limped back to London, they were only good for salvage.

CONTINUE to read the CAPTAIN JOHN SMITH

The Failed New England Colony (continued)

A hard man to kill, Smith decided to make another fishing run to build back his cash and investor confidence. Disaster struck again. Still in 1615, just days out of port, his small ship was approached by pirates. Amazingly, Smith knew the captain from his days as a soldier of fortune, and convinced the enemy ship to join him on a profitable fishing run to New England. But Smith never arrived. Both ships were now captured by French pirates who were feeding off European traders in the increasingly trafficked route to the Americas. Although his two ships escaped, Smith was held captive aboard the French ship for months. Trapped, frustrated, Smith used the time to write another book.

John Smith got away, of course, because as we all know by now, he was a very hard man to kill. Reportedly sheltering his precious manuscript, he stole a dory and slipped away when the French pirates were caught in a storm near their own homeland. Afraid of being hanged as a pirate, Smith turned himself in to the French authorities, even managing to get a goodly reward for fingering the actual pirates.

But it was the last sunset for John Smith the colonist. Despite the success of his next chart-topping book, "A Description of New England," the man with the best plan in London couldn't raise tuppence from his former investors. Smith reportedly did meet with a group of strange religious fanatics known as Separatists who were heading to Virginia, but found their way instead to one of Smith's favorite New England sites at "New Plymouth" in 1620. A few years later, in 1623, Smith's former close friend and supporter Sir Ferdinando Gorges helped pay to establish settlements on the Piscataqua River, another one of Smith's target colony sites, near what would become Dover and Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Captain Smith died in 1631, about the time a small group of colonists were settling in at Strawbery Banke in New Hampshire. He was 51. In his final years Smith wrote many more books, books including the story of "The Starving Time" in Jamestown Colony and about his adventures with the princess Pocahontas, who died while living not far from Smith in England.

For 400 years now, John Smith's reputation has risen and fallen on the relentlessly fickle seas of history. He's been lampooned on the Elizabethan stage, skewered by critics as a braggart and a liar, cast in bronze on the shores of the James River, cut into stained glass in St. Sepulcher's Church in England where he's buried, and portrayed by the voice of Mel Gibson in a Walt Disney's Pocahontas cartoon. Smith's reputation, it seems, is as hard to murder as the old soldier himself.

New England, above all, was going to be his monument. That was the plan anyway – to build a practical, industrious, profitable community. All Smith wanted, for the rest of his life, was one more crack at the game, one last chance to prove that he was right and everybody else was wrong. His victory was so close, Smith could taste it. But his scorecard just didn't tally. Sometimes History, to paraphrase Ronald Regan, can be an evil umpire.

READ about Nh explorers MARTIN PRING and DAVID THOMSON

Key Sources: Noel B. Gerson, The Glorious Scoundrel, Dodd, Mead & Co, NY, 1978 and Philip L. Barbour, The Three Worlds of Captain John Smith, Houghton, Mifflin, Boston, 1964.

Copyright © 2005 by J. Dennis Robinson. All rights reserved. Originally published here in 1999. Pictures include an early postcard from Virginia, an and two early illustrations of Smith's adventures from printed version in the SeacoastNH Image Library.