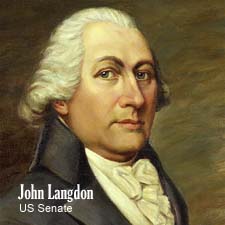

| Governor John Langdon |

FRAMERS OF FREEDOM

A historian once said that the history of New Hampshire from the beginning of the Revolutionary War until the beginning of the nineteenth century was little more than the history of John Langdon. While that is an overstatement, few other men were as influential in both state and national politics as was Langdon. As a member of the Continental Congress, he has also earned his place in history of the nation.

On December 14, 1774, John Langdon became one of the first prominent Americans to risk hanging when he led the raid on Fort William and Mary. From that day until 1812 when he retired from public life, Langdon remained a dominant political figure.

Sea Captain To Privateer

John Langdon was born on June 26, 1741, on the Langdon family farm near the head of the Sagamore Creek in Portsmouth. He was a fourth generation American, a member of an old and established New Hampshire family. The only school he ever attended was the public grammar school of Portsmouth, but although he had little interest in scholarship, he possessed a keen mind and a remarkable memory. Soon after he left school he went from the farm to the counting rooms of Portsmouth, following the example of his older brother, Woodbury Langdon.

With the help and guidance of his brother and a prominent merchant named Daniel Rindge, John Langdon's career moved rapidly. He was a sea captain by the time he was 22, sailing Rindge's sloops and brigantines over the Atlantic trade routes. John Langdon enjoyed the dashing life of a sea captain and being alert and ambitious, he did a little speculating of his own along with his regular duties. He was developing a good business mind and a start on his own fortune.

Just as John Langdon's career as a merchant was beginning, British trade restrictions dealt American commerce some painful blows. The American Revenue Act of 1764 and the Stamp Act of 1765 slowed commercial activity in Portsmouth. Langdon fell victim to British trade regulations when a ship on which he had a cargo of sugar and rum was seized and condemned by an admiralty judge. Langdon felt the seizure was due to "private pique" and appealed the judge's decision, but he lost his appeal and his cargo.

The Tea Act of 1773 brought a rumble of dissent from the colonies and pushed John Langdon into politics. On December 16, 1773, Boston had its Tea Party. The same day Portsmouth held a town meeting and passed a tea resolve designed to prevent the landing of any tea. The citizens of Portsmouth appointed Langdon to a committee designed to assure compliance with the resolve and to a Committee of Correspondence which was to maintain communications with the other colonies.

On October 19, 1774, King George III issued a royal order banning the export of powder and arms to America. This was supposed to be a sccret, but word got out and reached Portsmouth along with rumors that British troops were on the way from Boston to seize the powder at Fort William and Mary in New Castle. In order to insure a supply of powder and arms with which to defend New Hampshire, John Langdon led 400 men against the fort. The Americans quickly subdued the six man guard force, hauled down the Union Jack, broke open the powder magazine, and departed with 100 barrels of powder.

CONTINUE Life of John Langdon

LANGDON IN THE REVOLUTION (Continued)

Of Politics And Wealth

In 1775 John Langdon was elected as one of New Hampshire's representatives to the Second Continental Congress. At that time Portsmouth was suffering from the lack of trade and the people needed work, so when Congress voted to build 13 frigates, John Langdon managed to have one assigned to Portsmouth. He returned to Portsmouth early in 1776 to oversee the building of the vessel.

After building the "Raleigh", Langdon won contracts for two ships, "Ranger" and "America". Langdon recommended John Paul Jones as captain of the "Ranger", but the two men remained at odds over the building and outfitting of both ships.

In March of 1776, the Continental Congress legalized privateering as a means of attacking Britain's economic backbone, its merchant marine. John Langdon resigned from Congress to accept the lucrative position of agent of prizes for the colony of New Hampshire. He took charge of the sale of all prizes brought into Portsmouth and amassed a fortune on the side by outfitting several privateers of his own.

In March of 1776, the Continental Congress legalized privateering as a means of attacking Britain's economic backbone, its merchant marine. John Langdon resigned from Congress to accept the lucrative position of agent of prizes for the colony of New Hampshire. He took charge of the sale of all prizes brought into Portsmouth and amassed a fortune on the side by outfitting several privateers of his own.

Langdon was elected speaker of the New Hampshire House in December, 1776 and he held that position until 1782. As speaker he displayed great ability in guiding the passage of legislation during the critical war years. During these years he also presided over various state conventions called to deal specifically with such matters as currency and a new state constitution.

Politically, Langdon was often at odds with Weare, Bartlett and their associates. The legislature was dominated by the small rural towns, and their aims for the new state were not necessarily the same as those of mercantile Portsmouth. Langdon was quick to support his fellow townspeople, especially, his critics believed, when it seemed to be financially advantageous to do so.

He used all his influence to be named continental agent, but had to resign from the Continental Congress to accept the lucrative position. As agent and as the owner of seven privateers, he became wealthy while many others who were involved in the civil government placed public service ahead of personal finances. Langdon also promoted the political career of his brother, Woodbury, whose loyalties were questioned by many. All these factors made Langdon a controversial person in state government. While he retained his house speakership, it is significant that he was never appointed to the powerful Committee of Safety. Langdon might well be contrasted with William Whipple. Also a Portsmouth merchant, Whipple was appointed to the Committee of Safety and while friendly with Langdon, he was politically associated with Weare and Bartlett and certainly above reproach in his public service.

Perhaps Langdon's greatest contribution in the legislature was to pressure the state toward fiscal responsibility. He was an early advocate of taxation, price controls and the use of silver and gold instead of paper currency. He also led the opposition to a stiff confiscation act against Loyalists who had fled the state. He reasoned that the taking of property would result in embezzlement and that the British might take similar action against Americans with property in England.

Like many other men of this period, Langdon also had military aspirations, although he complained in a letter to Bartlett that since he and other merchants of the Piscataqua had been passed over in favor of others, he wouldn't accept a commission from the legislature if one were to be offered. Nevertheless, as a colonel, he did lead a voluntary company to Saratoga, where he witnessed the surrender of Burgoyne, and in the summer of 1778, he was in command of 46 men as part of John Sullivan's army in Rhode Island. It is doubtful that he saw any action at either time.

When Ticonderoga fell to the British under Gen. Burgoyne in July, 1777, there was a general fear in New Hampshire that the british would soon cross the Connecticut. The state legislature desperately needed to raise an army to protect the western frontier, but New Hampshire had no money. At the moment of despair, legend has it, John Langdon, then speaker of the house, rose before the legislature and said, "I have three thousand dollars in hard money. I will pledge the plate in my house for three thousand more, and I have 70 hogsheads of Tobago rum which shall be disposed of for what it will bring. These and the avails of these are at the service of the state. If we defend our homes and our firesides, I may get my pay; if we do not defend them, the property will be of no value to me." It is not clear whether thc story is true, or whether Langdon donated personal funds to the cause, but the legislature managed to provide backing for troops.

CONTINUE Life of John Langdon

LANGDON AFTER THE REVOLUTION (Continued)

NH Gov And 1st Senator

New Hampshire's Gen. John Stark organized the men and led them into Vermont. The army met Burgoyne's advance guard at Bennington and won a decisive victory, sparing New Hampshire from any British aggression. The end of the war found John Langdon in the thick of New Hampshire politics. Elected to the Continental Congress in 1783 and '84 he declined to serve, choosing instead to remain in New Hampshire. In 1784 he was a state senator from Rockingham County and in 1785 was elected president of New Hampshire.

By 1786 the infant United States was in trouble because the federal government was not strong enough to regulate the country. John Langdon favored a strong federal government, and when a constitutional convention was called to restructure the government, he was elected as a delegate. He worked on the Constitution in Philadelphia and then went to New York as a delegate to the Continental Congress and helped win approval for the new document. He returned to New Hampshire late in 1787 and turned all his ability and influence to the task of getting the ratification convention to approvc the Constitution. This it did on June 21, 1788, as New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify, making the Constitution law. Langdon's satisfaction in the matter is very evident in a letter he wrote to George Washington on the same day, in which he said: "I have the great pleasure of informing your Excellency that this State has this day adopted the Federal Constitution, 57 years 46 days-there by placing the Key Stone in the great arch. "

In November of 1788 the New Hampshire Legislature elected John Langdon as a senator and early in 1789 he traveled to the capital in New York City to attend the first meeting of the United States Senate. The Senate elected him its president and in this role he counted the votes of the electoral college in the first national election. To Langdon fell the honor of informing George Washington that he had been elected president, and on April 30, 1789, he administered the oath of office to the nation's first chief executive.

John Langdon served New Hampshire as senator until March of 1801 and was influential in forming the 3 policies of the United States in its early years. Then he returned to New Hampshire and served as state senator, as speaker of the house, and as governor for six terms. In 1812 he turned down the Republican nomination for vice president of the United States and retired from public life. In 1813 his wife died and part of his great spirit died with her. Langdon devoted his remaining years to religious matters and on September 18, 1819, he died in his mansion on Pleasant Street in Portsmouth, ending an era in the state's history.

By Steve Adams. Originally published in "NH: Years of Revolution," Profiles Publications and the NH Bicentennial Commision, 1976. Reprinted by permission of the publisher. This article first appeared online here in 1997.

About the Langdon Portrait at the top of the page: It was painted by Hattie Elizabeth Burdette (1872 - 1955) for the US Senate in 1916 after an earlier portrait by James Sharples. Langdon was the first president pro tempore of the Senate and this portrait is among 70 paintings owned by the Seanate including an image of John Paul Jones.