| Governor John Wentworth |

LAST OF THE NH ROYALS

Born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire’s last British leader did his best to keep peace, but John and Frances Wentworth had to flee. Royal Governor at the breaking point of the Revolution, Wentworth was in the wrong place at the wrong time. Despite his friendship with his citizens, Wentworth and his family were driven out of Portsmouth in 1775, never to see his homeland again.

READ: The Other Lady Wentworth

In 1778 as war raged in America, John Adams was in France attempting to obtain military and material aid for the infant United States. One May evening he left his box at a Paris theater. Suddenly, as he later wrote, "a Gentleman seized me by the hand. I looked at him.--Governor Wentworth, Sir, said the Gentleman.-- At first I was somewhat embarrassed, and knew not how to behave towards him. As my Classmate and Friend at College and ever since I could have pressed him to my Bosom, with the most cordial Affection. But we now belonged to two different Nations..at War with each other and consequently We were Enemies."

Adams, aware that the French police were watching their every move and unsure of how to respond, was visibly relieved when Wentworth took the initiative and made small talk inquiring after his father and friends whom he had left behind in America. He then asked Adams about the health of Dr. Franklin and said he must come out to Passy to pay his respects. After Wentworth's visit several days later, Adams seemed pleased to be able to say of his old friend, "Not an indelicate expression to Us or our Country or our Ally escaped him. His whole behavior was that of an accomplished Gentleman."

Adams, aware that the French police were watching their every move and unsure of how to respond, was visibly relieved when Wentworth took the initiative and made small talk inquiring after his father and friends whom he had left behind in America. He then asked Adams about the health of Dr. Franklin and said he must come out to Passy to pay his respects. After Wentworth's visit several days later, Adams seemed pleased to be able to say of his old friend, "Not an indelicate expression to Us or our Country or our Ally escaped him. His whole behavior was that of an accomplished Gentleman."

John Adams was a man of volatile passions and maintained a bitter resentment against those Americans who had remained loyal to England. Yet here, in 1778, with the United States in the depths of a struggle for survival, Adams had kind words and an obvious warm feeling for exiled Governor John Wentworth of New Hampshire. Adams' reaction was not unusual, for John Wentworth engendered less ill-will among Americans than almost any other highly placed British official in the colonies. Yet, in spite of favorable sentiment, Wentworth could not avoid the decree of history and became one of the tragic figures of the American Revolution.

Among Portsmouth Royalty

Born in Portsmouth in 1737, John Wentworth came from New Hampshire's most politically prominent and powerful family. In 1751 at the age of fourteen John entered Harvard College, where he first met John Adams. Each class was ranked according to family social standing. Of twenty five members of the class of 1755, Wentworth was placed fifth; Adams, the son of a Braintree farmer, was fourteenth. Wentworth seemed to have little affection for Harvard and could not even generate enthusiasm for commencement, one of the few great regional holidays in New England. As his college days neared an end he wrote to a friend, "I shall promise myself the pleasure of your company to see me perform a number of ridiculous Ceremonies, which custom has rendered necessary if we intend to keep on good Terms with the World, & you know that is very necessary." With graduation out of the way, John returned to Portsmouth to work in the business of his father, Mark Hunking Wentworth, merchant, mast contractor and one of the wealthiest men in New Hampshire.

John Wentworth spent the next eight years establishing himself in Portsmouth's mercantile aristocracy. He had done so well by 1763 that when circumstances demanded the presence of someone in England to protect Wentworth family interests, he was chosen to go. John welcomed the opportunity, for it also provided a chance to round out his education. A trip to England was for young Colonial gentlemen the equivalent of the European "grand tour" enjoyed by sons of the English aristocracy.

In England, it was not long before John Wentworth made the acquaintance of Charles Watson-Wentworth, the second marquis of Rockingham, reportedly while betting on the noble man's horses at the racetrack. The two, who were distantly related, got along well and John soon became a frequent visitor at Wentworth-Wood house, Rockingham's country estate in Yorkshire.

As time went on, this friendship became increasingly important, not only for John but for the entire Wentworth family. When it became apparent that his aging uncle, Governor Benning Wentworth, was in trouble with the English government and about to be removed from office, John wrote a defense of his uncle's actions for Rockingham. As a result, the old governor was allowed to resign in dignity instead of being ignominiously dismissed.

CONTINUE the life of JOHN WENTWORTH

LAST OF THE NH ROYALS (Continued)

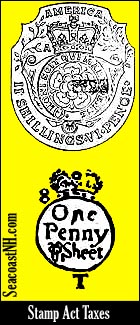

The "Totally Obnoxious" Stamp Act

In the summer of 1765 Rockingham was placed at the head of the British ministry. Faced almost immediately with an explosive situation in the American colonies precipitated by the Stamp Act, he turned for advice to John Wentworth. In a long and detailed description of the colonies, Wentworth explained to Rockingham the hardships imposed on the Colonial economy by the Stamp Act and advocated its repeal for the good of all British trade. More directly, John wrote to Daniel Rindge in Portsmouth that the Stamp Act was "totally obnoxious" and clearly showed the previous administration's "ignorance of the Colonies." It is difficult to say how much influence Wentworth's opinion carried, but in the spring of 1766 the controversial act was repealed. And in the summer of that same year, before he went out of office, Rockingham saw to it that John Wentworth, at the age of twenty-nine, was appointed governor of New Hampshire to replace his departing uncle.

Despite some resentment that had built up against the Wentworths during their long control of New Hampshire politics, John Wentworth was extremely popular when he took office in 1767 and he remained well liked through most of his governorship. He bore none of the haughtiness often associated with his uncle Benning, and always seemed to maintain the common touch. He was small in stature but uncommonly handsome and consistently affable. On one of his many expeditions into the interior, a backwoods settler unabashedly told him he was "getting leetler and leetler." The governor just grinned.

Despite some resentment that had built up against the Wentworths during their long control of New Hampshire politics, John Wentworth was extremely popular when he took office in 1767 and he remained well liked through most of his governorship. He bore none of the haughtiness often associated with his uncle Benning, and always seemed to maintain the common touch. He was small in stature but uncommonly handsome and consistently affable. On one of his many expeditions into the interior, a backwoods settler unabashedly told him he was "getting leetler and leetler." The governor just grinned.

In 1769 when he married his cousin, Frances Atkinson, just ten days after her first husband's funeral, this seeming breach of social decorum barely caused a stir. In a rather defensive letter written a year later to Rockingham, Wentworth explained his action as the result of pressure from his parents and uncle to get married.

As governor, John Wentworth accomplished much for the province and its people. Always interested in the development of New Hampshire's interior, he made the terms of land acquisition as easy as possible. In another matter, he sided with the House of Representatives against the Portsmouth merchant aristocracy that dominated the Council. Wentworth wanted to divide the province into five counties, thus sparing those living on the frontier the hardship of long trips to Portsmouth to conduct all their legal business. Wentworth eventually won. He was also among those responsible for the establishment of Dartmouth College in what was still the wilderness of the upper Connecticut River valley.

John Wentworth, of course, also had some enemies. If they had been able to form an organized opposition, they would have had a good chance to unseat him in 1772-73 when a disgruntled councilor, Peter Livius, brought charges in England against the governor for alleged misconduct. When both parties were ordered to produce evidence, Wentworth amassed an impressive pile of favorable depositions, including one from John Sullivan, who in a very short time would be one of the leaders against royal authority in New Hampshire. Livius also got depositions against the governor, but Wentworth was eventually exonerated.

The years of John Wentworth's governorship coincided with the period of rising conflict between England and her American colonies over colonial rights within the British Empire. As with the Stamp Act, Wentworth was distressed by what he considered stupid British policy, but he would not argue against it on constitutional grounds. Wentworth felt it was the British government's prerogative to pass any acts, right or wrong, concerning the colonies, and he told the provincial Assembly it was their duty to declare "their Obedience to the Authority of Parliament in all Cases." As governor, his job was to uphold that authority. In this, Wentworth was lucky, for there was little ferment in New Hampshire. There were no Patrick Henrys or Sam Adamses and little discussion of great political principles in this small northern colony. Thus Wentworth was able to maintain his authority for a relatively long time.

Escape to Halifax, Nova Scotia

But New Hampshire was one of the continental colonies and it could not avoid the onrushing events that eventually engulfed them all. John Wentworth was caught in the middle. He could not continue to uphold British authority and still retain the confidence of the people. When he tried to do both, he was caught. In October, 1774, he secretly hired New Hampshire carpenters, not telling them where they were going, to help Gen. Gage build barracks for his troops in Boston. When this uncharacteristic act of duplicity was discovered, John Wentworth's credibility was lost. In December, when he learned of an imminent attack on Fort William and Mary, he could find no one even willing to go and warn the small garrison stationed there. In the spring he attempted to "pack" the Assembly with friends, and as a result found a cannon aimed at his front door. In the night of June 13, 1775, he gathered up his wife and their five-month old son and fled to the fort in New Castle under the protective guns of H. M. S. Scarborough. In August when the Scarborough readied to sail for Boston, Governor Wentworth had no choice but to board and sail with her.

John Wentworth spent the war years in exile, waiting for the restoration of order and authority in New Hampshire. After the battle at Yorktown, however, he realized that he could never go back to his native province. He gave up his home, his position and all of his property for the royal cause, and for the rest of his life he remained a loyal servant of the king. In 1783 he returned to North America as surveyor general of the woods in Canada, and in 1792 received appointment as governor of Nova Scotia. When Wentworth retired in 1808 at the age of seventy-one, he and his wife returned to England to live out their days on a meager pension. Yet one last tragedy awaited him.

In 1812 creditors hounded him for payment of debts incurred in his official capacity in Nova Scotia. To avoid prison, Wentworth, at the age of seventy-five and with his wife ill, was forced to flee at night under an assumed name. From Liverpool he embarked for Halifax where he could sell some property to meet his debts. Sadly, Frances Wentworth died during his absence. With no reason to go back, John Wentworth remained in Halifax until he died in 1820.

SEE MORE: Framers of Freedom

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Paul Wilderson holds a Ph.D. in early American history from the University of New Hampshire. His book, Governor John Wentworth and the American Revolution: The English Connection, is available from the University Press of New England.

Originally published in "NH: Years of Revolution," Profiles Publications and the NH Bicentennial Commission, 1976. Reprinted by permission of the publisher. First published online at SeacaostNH.com in 1997.