| First American Boy Books Born in NH |

BOYS WILL BE BOYS

Before Tom Sawyer there was Tom Bailey. The first American "boy book" was not only written here, but is deeply rooted in the history, landscape and lifestyle of Portsmouth, NH. So why don’t we celebrate that? Boys just wanna have fun too, and the "Return of the Sons" was a celebration of that fact.

MORE Seacoast Books

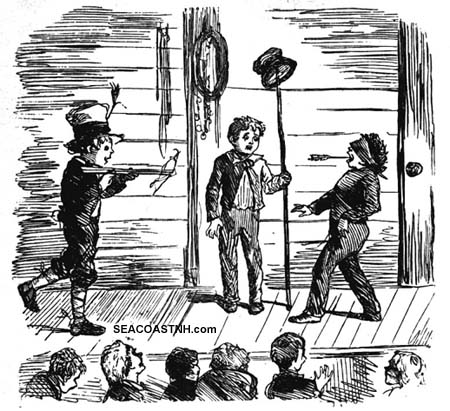

An entire literary genre started here. The "American boy" book was born in 1869 when Thomas Bailey Aldrich published the harrowing tale of his childhood on the streets of Portsmouth, New Hampshire. His "Story of a Bad Boy", a thinly disguised autobiography, broke new ground by recounting the real life of a mischievous 10-year old. In it, Tom Bailey runs away from home, sets fire to a stagecoach in Market Square, knocks himself unconscious with gunpowder, shoots a friend with an arrow and falls in love.

Writer and critic William Dean Howells immediately recognized that this book was something special. In the January 1870 issue of Atlantic Monthly Howells wrote:

Writer and critic William Dean Howells immediately recognized that this book was something special. In the January 1870 issue of Atlantic Monthly Howells wrote:

"Mr. Aldrich has done a new thing in American Literature…No one seems to have thought of telling the story of a boy’s life with so great desire to show what a boy’s life is, and so little purpose of telling what it should be."

Aldrich was just 32 when he revisited his grandfather’s house in Portsmouth and composed his most popular novel. He finished the novel late in 1868 and his twin sons were born the same week. Aldrich did not try to teach his readers how to be good little boys as was the common theme of books for boys in his time. Instead he recounted the dangers, thrills, triumphs and failures of his childhood days in classical terms. His account of a huge snowball fight between North and South End boys of Portsmouth reads like an epic battle from history, complete with battle strategy diagrams.

The book was a hit with young readers, parents and teachers and "The Story of a Bad Boy" was reprinted in dozens of editions and remains in print to this day – making it a classic of American literature. Mark Twain perfected the genre with his novels Tom Sawyer (1876) and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884). The two authors were friendly, and had it not been for Aldrich, Twain might have scrapped his book.

"I was just planning Tom Sawyer when he (Aldrich) was beginning the Story of a Bad boy," Twain told his biographer Albert Bigelow Paine. "When I heard that he was writing that I thought of giving up mine, buit Aldrich insisted that it would be a foolish thing to do. He thought my Missouri boy could not by any chance conflict with his boy of New England, and of course he was right."

CONTINUE with AMERICAN BOY BOOKS

LITERARY GENRE STARTS IN NH (continued)

But Portsmouth’s claim as the birthplace of the American boy novel does not end there. Both Twain and Aldrich were influenced by another writer who also grew up on the streets of Portsmouth. Benjamin Penhallow Shillaber was born in a tiny house on the North Mill Pond and moved to Boston at age 18 to seek his fortune in the printing business. Shillaber created the troublesome boy Ike Partington in the late 1840s as a comic partner to his popular character Mrs. Partington. The two country bumpkins appeared in close to a dozen books by Shillaber and were popular throughout the expanding nation.

Shillaber described Ike as a "human boy" and evolved a detailed theory about the developmental nature of boys at the onset of puberty. Boys at this age, he said, were distinct creatures that existed only to have fun. No matter how outrageous the "human boy" acted, Shillaber suggested, he should be allowed to go his own way, and no man should be judged by his actions as a youth.

"Ike was not a bad boy in the wicked sense of the word bad, "Shillaber wrote, "but he had a constant proclivity for tormenting every one that he came in contact with."

Clearly borrowing from BP Shillaber, Aldrich opened his groundbreaking novel by identifying himself as "a real human boy". He says:

This is the story of a bad boy. Well, not such a very bad, but a pretty bad boy; and I ought to know, for I am, or rather I was, that boy myself."

Mark Twain too was indebted to Shillaber’s "plaguy boy" Ike Partington. Shillaber was, ironically, the very first major national editor to publish the comic writing of the young Samuel Clemens, aka Mark Twain. As if in tribute, in his first edition of the novel Tom Sawyer, Twain included a sketch of Mrs. Partington on the final page.

The "American boy" genre lasted only a few decades. Authors Stephen Crane, Booth Tarkington and William Dean Howells all wrote their bad boy stories. Popular culture historians might argue that the "bad boy" genre did not die, but simply moved into movies and television. It shows up in early Little Rascals and Three Stooges through to Dennis the Menace, Beavis and Butthead, Dumb and Dumber, South Park and the MTV Wild Boyz and Jackass productions. While these characters may be descended from Tom Bailey and Tom Sawyer, they suffer from a Peter Pan syndrome in which men refuse to outgrow their boyhood ways.

CONTINUE with AMERICAN BOY BOOKS

LITERARY GENRE STARTS IN NH (continued)

But the American boy as invented by Aldrich, Shillaber and Twain was another thing. These 19th century boys acted young because they were young, usually between 10 and 12 years old. They lived in a time when many boys began their careers as early as 14 or 16. They were educated polite boys in their final wild years, not victims of arrested development like their modern counterparts.

In his book Being a Boy (1877) Charles Dudley Warner described boyhood as the ultimate condition, except that "just as you get used to being a boy, you have to be something else."

It is not by accident that the boy book was born here. Portsmouth tumbled into an economic decline at the turn of the 19th century, just as these future authors were growing up on the New Hampshire coast. Shillaber, Aldirch, publisher James T. Fields and others all left to make their fortunes elsewhere. Years later they attended a series of Portsmouth "homecoming" events during which these accomplished literary men shared nostalgic stories of their beloved home town. This nostalgia for the past was especially strong during the fast-paced, noisy, sooty Industrial Age. Portsmouth changed very little and so came to represent the happier and simpler "good old days".

BP Shillaber made this point in a few lines from a poem recited at the 1853 "Return of the Sons" celebration when he said:

And memories, like railroad trains

Come freighted full of Portsmouth Plains –

That greater field, in Boyhood’s view,

Than New Orleans, or Waterloo.

For Shillaber, tales of the Indian raids at "The Plains" in Portsmouth were more real to him than bigger events in history. Shillaber’s writing, like that of Aldrich and Fields and local historian Charles Brewster is thick with references to life in Portsmouth. Often their boyhood memories intersect, providing vivid pictures of early Portsmouth that should be studied and reprinted. Aldrich, for example, tells the story of Binny Wallace, a fictional boy who was swept out to sea by the fast Piscataqua tides. James T. Fields, who would become the most influential literary publisher in Boston, recalled that his entire Portsmouth class and their teacher were lost at sea during a Sunday picnic outing. Stories of snowball fights, club houses, sledding races and school thrashings appear again and again in these boy books, poems, speeches and letters. It is a rich untapped vein for local historians.

Portsmouth already has a boy book museum of sorts. The Thomas Bailey Aldrich Memorial on Court Street opened in 1908 and is now part of Strawbery Banke. Each room in the house has been carefully reconstructed to match the descriptions in "The Story of a Bad Boy". For a century these empty rooms have been a silent shrine to a book few now read and an author nobody knows. Yet Aldrich’s book still explodes with the sound of firecrackers and canon, shrieking adults, and laughing children. His depiction of "the human boy" is as relevant as ever, and Portsmouth’s place in literary history deserves to be celebrated, not entombed.

Perhaps this building could be re-born as the Bad Boy House, a hands-on museum that celebrates and explores the energetic life of the "human boy". Instead of empty rooms and old furniture, the Aldrich House might bring the history of the American boy to life. Tom Bailey could invite his friens Ike Partington, Huck Finn, Tom Sawyer and rascals to visit. Real boys and even girls could learn to tell their own stories. Teachers, psychologists, anthropologists, scientists and historians could debate how boys have or have not changed. Kids could just have fun while Portsmouth, at last, gets the credit it deserves.

Copyright © 2006 by J. Dennis Robinson. All rights reserved. This essay was abridged from the author’s recent address to the Portsmouth Historical Society entitled "Lively Boys! Lively Boys!" For further reading on this topic the author suggests the book Being a Boy Again: Autobiography and the American Boy Book by Marcia Jacobson, University of Alabama Press, 1994.