| Sam Walter Foss was NH Poet Laureate for the Common Man |

Sam Walter Foss penned his first verses at Portsmouth High School here in NH. He went on to gain popular fame for his comic and philosophic writing. His poem "The House by the Side of the Road" was among the best loved in the nation. His fame has faded, but unlike many poets of his era – his works are still readable and relevant.

Sam Walter Foss penned his first verses at Portsmouth High School here in NH. He went on to gain popular fame for his comic and philosophic writing. His poem "The House by the Side of the Road" was among the best loved in the nation. His fame has faded, but unlike many poets of his era – his works are still readable and relevant.

POEMS by Sam Foss and others

With two American poet laureates in a row coming from New Hampshire -- Donald Hall and now Charles Simic -- maybe something literary is literally alliterating in our water. Great poets blossom here, and none, for my money, was greater than Sam Walter Foss. He is known today, almost exclusively, for a bit of verse entitled "The House by the Side of the Road." The poem urges everyone to stop being cynical and scornful to their neighbors and "be a friend to man." It is sentimental, honest, proactive and optimistic – essential Foss -- but it is far from his best work. I know because I have a degree in English Literature, which is little more than a license to read books. I know, too, because Foss published five volumes of poetry, and I’ve read them all. This guy rocks.

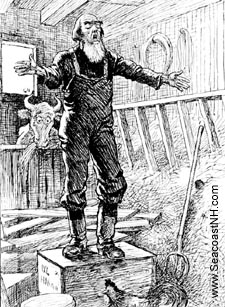

Foss was more philosopher than poet. His moral compass was dead on. He carried a healthy distrust for authority. He had no patience for lazy, pretentious or quarrelsome people. A humanist of the highest order, Foss believed entirely in the goodness of "the average man" and wrote entirely for a popular audience that he hoped to inspire with his "homespun" verse. It was his dedication to popular topics and clear writing, one literary critic has suggested, that doomed Sam Walter Foss to obscurity. He refused to write with the "imagist obliqueness" employed by "major" poets of his era. In other words, when Foss wrote, you knew what he was saying.

Foss was more philosopher than poet. His moral compass was dead on. He carried a healthy distrust for authority. He had no patience for lazy, pretentious or quarrelsome people. A humanist of the highest order, Foss believed entirely in the goodness of "the average man" and wrote entirely for a popular audience that he hoped to inspire with his "homespun" verse. It was his dedication to popular topics and clear writing, one literary critic has suggested, that doomed Sam Walter Foss to obscurity. He refused to write with the "imagist obliqueness" employed by "major" poets of his era. In other words, when Foss wrote, you knew what he was saying.

The world, for Foss, was an incredibly fascinating comic opera. The more powerful and rich men became, he continually points out, the sillier men become. If he wrote about a boy "who was dumber than snowbirds in summer," the boy was likely to grow up to be president. Foss was fascinated by careless commuters who consistently showed up at the railroad station "jest in time to miss the train." His hero is often a humble farmer, artisan or shopkeeper who comes up against local power brokers. He doesn’t always win, but he does the best he can.

In "The Logic of the Gun," a farmer posts 200 signs banning hunting on his property, then spots a man carrying a rifle. The farmer points to the sign. "You may have the rights," the hunter says, "but I have got the gun." In another poem, Foss plays the part of a storeowner who tries to join the local church, because he knows that is the best way to attract customers. Unwilling to have him as a member, the church elders stall the merchant by telling him to go off and talk to God. But the merchant returns a few weeks later and tells the shocked elders that he has, indeed, talked to God about joining their church. What did the Lord say? – they ask. The shopkeeper repeats the conversation:

"I’m trying to git in," sez I, "to the church of Elder Ford,

An they won’t let me in at all." "Don’t worry," sez the Lord.

"You’re not the only one," sez He, "they’ve laid upon the shelf.

I’ve tried ten years without success to git in there myself,"

CONTINUE SAM WALTER FOSS

Born in Candia, NH in 1858, Foss moved with this family to Portsmouth when he was a young teen and attended the local high school. Then, like so many of his Industrial Age generation, foss abandoned the family farm for the urban landscape. You can take the boy out of the country, as they say, but you can’t take the country out of the boy. Foss, like many poets of his era, spent the rest of his life living in the city and writing about the joys of rural life. But unlike most of his contemporaries, the poems of Sam Foss are still fresh and funny and poignant today.

The problem with poetry, as most modern poets know, is that almost nobody reads it, unless the poem is buried in a song lyric, turned into a jingle or rammed down one’s throat in school. That was not true in the 19th century when reading and writing poetry was a national pastime. Like many writers, Sam Walter Foss came to poetry through journalism, After graduating from Brown University, he tried to run his own newspaper in Lynn, MA. When a freelance humor writer failed to turn in his column, Foss took a hand at writing comic pieces. His readers loved them. Foss later wrote columns for humor magazines, The New York Sun, The Boston Globe and the Christian Science Monitor. Four hundred of his poems appeared in five popular collections

But Foss never made enough money writing poetry to quit his day job. In 1898 he accepted the position as city librarian in Somerville, MA, one of the most densely populated cities in America. True to his philosophy, Foss used every method available to put books in the hands of average readers. He promoted the revolutionary practice of allowing patrons to take books directly off shelves, without the help of a librarian. He pioneered the use of travelling book collections in public schools, factories, prisons and nursing homes. During his tenure, the Somerville Library was among the most-trafficked library in the nation. Foss held the library position until his death of a liver ailment in 1911. He married the one love of his life, had two children, and died before he was able to write longer, more serious verse. Many of his poems were knocked off for the daily and weekly columns he wrote for local newspapers.

Sam Walter Foss has no biographer. His books are long out of print. But thanks to a high school chum, E. Scott Owen, we have a rare snapshot of the artist as a young man. Foss lived with his family in a small farm by Goseling Road by what is now the Newington Mall. He walked two and a half miles each way, each day, to attend school in the ancient brick building near the modern post office on Daniel Street. He was stocky, deeply tanned, slightly stooped, and wore his curly hair "brushed smooth. Although Foss was witty and likeable, he was neither a scholar nor a leader. He seemed to have no interest in girls, and it would not have mattered if he did. The minute school ended each day a 1:30 pm, Foss hiked up his unfashionably "high tide trousers" and trudged home to the family farm. His school chum remembers only seeing him angry once, when another boy swore at him. He was distinguished, not by his features or deeds, but by his total honesty and dogged determination to go to college.

E. Scott Owen recalls an essay on that Foss wrote for the high school Natural History Society that met during the last hour of class every Wednesday. It really had nothing to do with Natural History, Owen writes in an unpublished memoir, but was a sort of literary forum. Foss wrote and read aloud little humorous poems to the delight of his classmates. One mocked the school "Growlers," who spent so much time complaining about others, that they accomplished nothing themselves. It was a theme Foss often returned to in his later poetry. But when selected to pen "something poetical" for commencement, Foss wrote a bland and serious farewell ode. His friend E. Scott Owen wrote the music. A frail broadside copy of the document still survives. The final somber stanza reads:

So when we close our education,

In the world’s great school of strife,

May our second graduation,

Fit us for a higher life.

Foss, of course, is talking about death here, but in fact, he did have a second graduation, and a third. Only two of the 19 Portsmouth High graduates from 1877 went on to advanced schooling. At that time, public schools were not adequate preparation for college. Foss got his Latin and Greek the next year at a prep school in Tilton, NH, before going on to Brown, where he worked his way through and was again, likeable, but unremarkable. When he consistently came up with "C" level work, his Portsmouth teacher reportedly said, "My boy, you know you want to be on good terms with both ends of the class." He was the ultimate common man.

But for Sam Walter Foss, being average was something to be proud of. Average men and women were uncorrupted, hard working, good-humored and resilient. The poet’s job, Foss believed, was to speak in an authentic voice that everyone could understand. His mission was not to use language to confuse or impress, but to use it like a bullhorn to call common people to step out of the crowd and perform great deeds. Foss ends his poem ‘The Man from the Crowd" this way:

We are waiting for you there --- for you are the man!

Come up from the jostle as soon as you can;

Come of from the crowd there, for you are the man –

The man who comes up from the crowd!

Copyright © 2007 by J. Dennis Robinson. All rights reserved.