| Goody Cole Accused as NH Witch |

FAMOUS SEACOAST PEOPLE

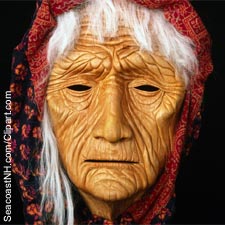

She will forever be the only New Hampshire woman ever convicted and jailed for witchcraft. The Hampton, NH story of Goody Cole is one we tell often, but not well. She was an elderly lady hounded out of her property by her fellow townspeople during New England’s shameful era of persecution. And when she died, legend says, the locals put a stake through her heart.

READ: First women executed in NH

SEE ALSO Witchcraft in NH

THE HEXPLOITATION OF GOODY COLE

Poor Goody Cole! Year after year we exhume her rotting legend just to sell a few more newspapers. It's not a pretty sight. We blood-sucking zombie journalists still stalk the grave of the only New Hampshire citizen convicted of witchcraft. Feeble, bent, starving and elderly - she was an easy victim in the late 1600s, and she remains an easy victim today.

We pick at her ancient bones symbolically, of course. That's because no one knows where Eunice "Goodwife" Cole is buried, or if she was buried at all. After being tried and condemned as the "witch of Hampton" in 1656, Goody Cole was confined in a bleak, cold Boston jail cell for much of her last twenty years. Her elderly husband William, just ten years older than William Shakespeare, died while she was in jail. Finally she returned to the colony of New Hampshire, then governed by the Puritans of Massachusetts Bay.

We pick at her ancient bones symbolically, of course. That's because no one knows where Eunice "Goodwife" Cole is buried, or if she was buried at all. After being tried and condemned as the "witch of Hampton" in 1656, Goody Cole was confined in a bleak, cold Boston jail cell for much of her last twenty years. Her elderly husband William, just ten years older than William Shakespeare, died while she was in jail. Finally she returned to the colony of New Hampshire, then governed by the Puritans of Massachusetts Bay.

She died alone in a small hut off Rand's Hill in the ancient center of Hampton. In her final days, the town government ordered that the "bewitched" woman be supported by the citizens who hated and feared her. Each week a different family was required to bring her food and fuel, or to pay the value of four shillings. One day, according to Joseph Dow's "History of Hampton," the smoke stopped coming from her chimney. The food stayed unclaimed at the door. In her 80s or 90s, disgraced and despised, Eunice Cole was dead, but her punishment was far from over.

One theory has it that the local citizens tossed her body in a nearby ditch. Another says they threw her off a cliff into the sea. A third says she was buried on the land that had once been her own 40-acre farm, the same property the town of Hampton took from Goody to pay the cost of confining her in that lonely Boston cell.

In all versions of the legend the fair citizens of colonial Hampton discovered the body of the "witch" and drove a wooden stake into her heart. Then, to protect themselves from her ghostly retribution, the impalers hung a horseshoe on the stake. It's all speculation, of course, ideas pieced together from European folklore and copycat tales of witchery in nearby Salem, Massachusetts.

So what are we to make of such wonderfully lurid stuff? It's all speculation, but the more we tell it -- the more we believe something wicked was afoot. The story of Goody Cole hunkers in the breakdown lane of Seacoast history like a gruesome traffic accident. We cannot look away.

No history of the region fails to mention Goodwife Cole, but as always it was John Greenleaf Whittier who took her story to the bestseller charts in 1864 with his poems "The Changeling" and "Wreck of the Rivermouth." Here Goody is linked to the demonic transformation of a baby and to an actual shipwreck of eight Hampton residents in 1657. Victorian folklorists like Samuel Adams Drake picked up on the story. Eva Speare included the Hampton witch in her popular 20th century books of New Hampshire lore, and the hex-ploitation continues. A few years back Channel 11 Public Television re-enacted the legend, right down to the colorful stake-pounding scene and replete with spooky music and sound effects. Indeed, it has become impossible to talk about Goody Cole in any other context.

There have been attempts to stop the Goody-bashing. In 1938 a Hampton group formed for the sole purpose of redressing the wrongs done to her. The group was called "The Society in Hampton for the Apprehension of Those Falsely Accusing Eunice 'Goody' Cole of Having Had Familiarity With the Devil." The long name was a publicity stunt. It worked.

THE HEXPLOITATION OF GOODY COLE continued

THE HEXPLOITATION OF EUNICE COLE (continued)

Copies of Cole's 17th century court records were ceremoniously burned and placed in an urn with soil from her supposed home and grave sites. The contrite citizens of Hampton promised to erect a stone monument and bury the ashes beneath it. The pardon was so successful, it made newspapers around the world.

It's ironic, says Hampton historian Bill Teschek, that the once-hated Eunice Cole has become the town's most famous citizen. School kids now swarm the Lane Library, devouring the scattered tidbits of fact and fable. Teschek has put everything he can find about Goody on the library's website, including Dow's detailed history.

Dow suggests that Goody was less than likable, unable to attract the affection of her neighbors. Hamptonians then described her as "ill-natured and ugly, artful and aggravating, malicious and revengeful," Dow writes.

Dow says that two elements converged to convict Cole based on hearsay and circumstantial evidence. She was, he says, a victim of the times, when witch-hunts were part of an American hysteria and superstition reigned. Goody received the concentrated "odium" of the people of Hampton, and her imprisonment soothed their angst. Secondly, he implies, Goody was itching for a fight.

She was condemned by the ancestors of Seacoast families, some still living here - Marston and Phibrick, Moulton and Drake. Goody was prone, it appears, to curse out her neighbors. One threat, a neighbor testified in Norfolk Court, led to the death of two of his cattle. When she told another citizen that she wished his calves would eat poisonous grass and die, the calves were never seen again. Goody said she knew there was a witch in town, that she knew of a bewitched person who had turned a man into an ape, and the ape looked like the Marston's child.

Not smart Goody Cole, in an era when a woman could be stripped and lashed in the public square for arguing with a town official. The crime of Eunice Cole was that she simply would not shut up. Like the cackling crone in the film "Wizard of Oz," Cole has been depicted as almost unsympathetic. She stood up for her rights in an era when she had none.

She was sent to jail three separate times on the scantiest of charges. Once she was convicted for trying to lure a girl into her hut by speaking through a dog, a cat and an eagle. In another court deposition, two citizens say they heard a scraping sound whenever they mentioned Goody Cole's name. It was on that kind of evidence she languished in prison through much of her golden years.

Harold Fernald has another theory, and he has earned the right to express it. Recently retired, Fernald taught New Hampshire History and Field Archeology for 41 years, most of that at Hampton's Winnacunnett School. He sees Goody Cole as the pawn in a political game at a time when religious patriarchs in towns like Hampton and Exeter exercised godlike powers.

William and Eunice Cole, Fernald notes, first came to Exeter as indentured servants of their London master. They were part of the upstart new colony at Exeter under Rev. John Wheelwright, who fled from the Puritan group at Plymouth Colony. For some reason, in 1640, the Cole's decided to move to the settlement at nearby Hampton two years after arriving in America. That parish was run by Rev. Stephen Bachiler, who was later kicked out of town for reportedly having an affair with a young female parishioner while he was in his 80s. (Bachiller moved to Portsmouth, unsuccessfully surd the people of Hampton, and died in England at age 100.) Wheelwright moved from Exeter to Wells, Maine, but was ousted from there and made a bid for control of Hampton. That left the Cole's back under the jurisdiction of the leader they had previously abandoned. They had a little land at the center "Ring" of town that others wanted. They were poor, elderly, and Eunice was a woman who spoke her mind. Do the math.

For the record, Harold Fernald played Rev. Wheelwright in the eerie television docu-drama. He's the one who impaled local actress Priscilla Triggs Weeks with the wooden stake on the beach. In fact, the two amateur thespians have been acting out the Goody Cole story for decades, to the horrible delight of school children across New Hampshire.

Fernald remembers attending the 1938 ceremony to exonerate Eunice Cole. He was about seven at the time. He says the ceremony was followed months later by one of the most devastating hurricanes to hit the seacoast. In all the commotion, the town fathers forgot to honor their promises to Goody Cole. No monument was raised and the ashes from the burned documents were never buried.

After 1938 there were many sightings of a mysterious old woman wandering the streets of Hampton, Fernald says as if he has told the story many times before. One was even reported by a part-time Hampton cop, whose name, for the record, was Harold Fernald. In 1963 Fernald talked the city into erecting a large erosion stone outside the Tuck Museum, which sits on the presumed site of Goody and William Cole's farm. He did it, he says, to allow Goody's soul to find peace and quiet. Three hundred years of mocking disrespect and exploitation was enough for any woman. The Tuck Museum now houses an exhibit telling the story of Goody Cole.

But there's an epilogue here. Harold Fernald admits that the urn of ashes never did get buried under that rock as promised. He plumb forgot, and it's still on display at the Tuck Museum. As much as he wants Goody's ghost to find eternal rest, Fernald admits, he's grown awfully fond of her, fond of telling her sad story. Things just wouldn't be the same around Hampton without Goody Cole to kick around.

Copyright © 1997 by J. Dennis Robinson/ SeacoastNH.com. Updated 2006. All rights reserved.