|

FRESH STUFF DAILY |

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

SEE ALL SIGNED BOOKS by J. Dennis Robinson click here |

||

He was first to cross the English Channel in a hot air balloon. He was first to successfully parachute to the ground. But when he took his balloon aloft in Portsmouth, New Hampshire in 1796, a jealous local newspaper suggested his invention was only good for scaring cats.

On the cold afternoon of February 18, 1796, the winter calm that muffled the streets of Portsmouth was broken by the roll of drums and the piping of fifes. Instantly, a certain restlessness that had pervaded the seaport all morning was transformed into excitement. The martial music was a signal that this day would see the success or failure of French balloonists Jean-Pierre Blanchard’s "Aerostatic Experiment" – an exhibition of a sort that few New Hampshire citizens had ever witnessed, and that few would ever see again.

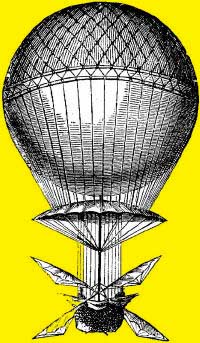

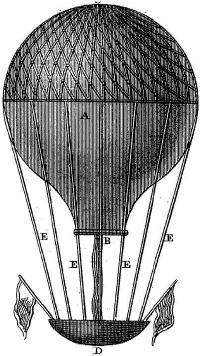

Beneath the great globe hung a large umbrella-like device decorated to resemble a red, white, and blue French liberty cap. This was the famous parachute, a new invention whose amazing ability to retard the fall of an airborne object had been conclusively demonstrated by the very aeronaut who was now in Portsmouth. Below the parachute swung the "car" of the balloon, a wicker basket destined to carry "several living quadrupeds"—probably recruited from Portsmouth’s back alleys—high into the ether.

But the experiment had not yet ended. As the aerostatic machine climbed higher, a slow fuse was burning above the parachute. Suddenly, as a seemingly immense altitude, a charge exploded. The balloon shot upward, freed of its burden, and the parachute and car dropped toward the earth. The parachute blossomed into a huge tri-colored umbrella, drifting slowly in the almost imperceptible breeze. No longer counterbalanced, the balloon overturned, spilled it "aerial fluid" and fell in a majestic parabolic curve. Descending lazily, the parachute safely returned the car and its living cargo to the earth. The New Hampshire Gazette, which had been favored with most of Blanchard’s advance advertising, estimated Blanchard’s audience at nearly 3,000 "who appeared very well satisfied at this sight, the first of the kind ever seen in this State." STORY CONTINUED ON NEXT PAGE JEAN-PIERRE BLANCHARD IN NEW HAMPSHIRE Not everyone was enthusiastic, however. Blanchard had not purchased much advertising in the Portsmouth Oracle, rival to the Gazette, and the Oracle reporter was disinclined to praise the enterprise that had enriched a competitor. He reported Blanchard’s audience at only "fifteen hundred" who appeared to be ----."

Blanchard’s Gallic temper only drew a taunting reply that described the aerial machine as a "----, I don’t know what it was, some call it a Balloon, others call it a Contrivance to kill Cats, or at least to frighten them to death." Realizing the futility of sparring with an anonymous opponent, Blanchard decamped angrily from Portsmouth. On April 9, 1796, he published in the Providence Gazette the advertisement for his balloon ascent, with an announcement of his intention to repeat the experiment for the inhabitants of Rhode Island. Soon afterward, Blanchard appears to have returned to Europe.

Having perfected the basic components of his apparatus, Blanchard commenced a series of aerial experiments that quickly established him as a leader in the new science of aerostation. On January 7, 1785, Blanchard and Dr. John Jeffries of Boston, Massachusetts, embarked on a trip that had never before been attempted, and that many regarded as impossible: a passage across the English Channel. During the perilous crossing, the balloon dipped dangerously close to the sea and the two passengers were forced to lighten the craft by throwing overboard everything they had in the car, including most of their clothing. The balloon finally gained altitude, soared over the French coast near Calais, to the accompaniment of a cannon salute from Fort Rouge, and alighted in the Forest of Guines. Instantly, Blanchard and Jeffries were famous throughout the world. Continuing his experiments, Blanchard set the world’s record for distance with a flight of some 300 miles in August, 1785. He began to investigate the reliability of his parachute, first dropping a dog safely from his balloon, and finally descending himself on a flight in England—though at the cost of a broken leg. These numerous trials of the parachute of course enabled the aeronaut to feel confident of the success of his Portsmouth demonstration. In the fall of 1792 Blanchard decided to try his fortune in a new country, and he embarked on a ship Ceres, bound for Philadelphia. Realizing he would have to live by his wits in his new home, Blanchard brought several balloons with him, together with the necessary chemicals and apparatus for generating hydrogen gas and several other inventions certain to draw generous patronage from the mechanically minded Americans. Before the performance in Portsmouth, he made a manned ascension in Philadelphia and in the same city experimented with sending animals aloft. In the fall of 1795, Blanchard proposed a tour of the northern cities, hoping to find unjaded Americans who "had as yet only heard of the brilliant triumph of aerostation," and who were "worthy of enjoying the sublime spectacle that it affords." Thus originated the Portsmouth flight of February, 1796, as well as ascensions in Boston and Salem.

Shortly after his New England tour, Blanchard appears to have returned to Europe. It is doubtful whether his American experience proved profitable; he may have lost money in many towns. The expense of generating hydrogen gas, then accomplished by adding sulphuric acid to iron filings in closed barrels, was considerable. Blanchard himself remarked that he had "brought with me from Europe only 4200 weight of vitriolic acid, the quantity to effect my own ascension, once." He estimated that a similar amount of acid, if it could be procured in America at all, "would cost at least 100 guineas" –the equivalent of more than $400. Whether or not Blanchard profited from his stay in the United States, the American people never forgot him. In February 1808, he had a heart attack while on a balloon flight over The Hague in the Netherlands. Blanchard fell more than 50 feet to the earth and died the following month. Even after he died on March 7, 1809, American newspapers continued to carry fascinating accounts of the exploits of his widow, herself an aeronaut with scores of flights to her credit. Finally, at the end of August, 1819, the New Hampshire Gazette carried one last, tragic dispatch from Paris. Madame Blanchard had attempted an illuminated nighttime ascension at Tivoli. The fireworks with which she lighted her flight had ignited the highly flammable hydrogen in the balloon, and she had plunged to a fiery death. Her tragic end wrote a final chapter to the saga of the Blanchards, a story that had thrilled Europeans and had once caused all of America to lift her eyes to the sky. This article first appeared in NH Profiles, June 1976 and is reprinted by permission of the author. A former curator at Strawbery Banke Museum, today James L. Garvin is the NH state architectural historian at the NH Division of Historical Resources. Please visit these SeacoastNH.com ad partners.

News about Portsmouth from Fosters.com |

| Thursday, April 25, 2024 |

|

Copyright ® 1996-2020 SeacoastNH.com. All rights reserved. Privacy Statement

Site maintained by ad-cetera graphics

Link Free or Die

Link Free or Die

As the town clock approached the hour of three, crowds began to gather at every vantage point. Already the balloon was being filled in the enclosed garden behind the Portsmouth Assembly House on Vaughan Street. Those who could afford a dollar each for tickets were admitted to the garden, where they could get a better view of the immense flying apparatus. The balloon, fabricated from some 150 yards of silk taffeta, had inflated to a height of 23 feet and a diameter of 17. It held 2573 cubic feet of a mysterious "aerial fluid" that caused it to tug at its tethers like a living thing.

As the town clock approached the hour of three, crowds began to gather at every vantage point. Already the balloon was being filled in the enclosed garden behind the Portsmouth Assembly House on Vaughan Street. Those who could afford a dollar each for tickets were admitted to the garden, where they could get a better view of the immense flying apparatus. The balloon, fabricated from some 150 yards of silk taffeta, had inflated to a height of 23 feet and a diameter of 17. It held 2573 cubic feet of a mysterious "aerial fluid" that caused it to tug at its tethers like a living thing. Soon a hushed multitude of thousands listened anxiously for the strike of the town clock in the North Church steeple. Many stood within the assembly house courtyard, but most crowded the streets or gazed from the roof scuttles of private homes, expectantly searching the skyline in the direction of Vaughan Street. Suddenly they saw it; a majestic sphere, as tall as the average house, rose swiftly, irresistibly and in perfect silence toward the heavens. As the great form cleared the rooftops, the fluted surface of the balloon, the partially folded parachute and the small basketwork car were all silhouetted against a clear sky. Gasps of awe and admiration escaped the crowd and delighted huzzas filled the crisp air.

Soon a hushed multitude of thousands listened anxiously for the strike of the town clock in the North Church steeple. Many stood within the assembly house courtyard, but most crowded the streets or gazed from the roof scuttles of private homes, expectantly searching the skyline in the direction of Vaughan Street. Suddenly they saw it; a majestic sphere, as tall as the average house, rose swiftly, irresistibly and in perfect silence toward the heavens. As the great form cleared the rooftops, the fluted surface of the balloon, the partially folded parachute and the small basketwork car were all silhouetted against a clear sky. Gasps of awe and admiration escaped the crowd and delighted huzzas filled the crisp air. This puzzling and slighting notice drew an immediate rejoinder from an enraged Blanchard. "As the Connoisseurs were satisfied with it," retorted the aeronaut, "pray get your correspondent to explain the meaning of the points (hyphens) in the last phrase of his paragraph, and tell him not to be ashamed to put his name to his production. This superb experiment has been admired by the wise of the old and the new world, and celebrated by the able poets of our age. . . If this which has excited the curiosity of all classes of people, both in Europe and America, appears so trivial in his eyes, do request him to be kind enough to teach me how to realize Monsieur Bergerac’s novel, which sends his hero to the moon; or else tell him to shut up his Ebenezer."

This puzzling and slighting notice drew an immediate rejoinder from an enraged Blanchard. "As the Connoisseurs were satisfied with it," retorted the aeronaut, "pray get your correspondent to explain the meaning of the points (hyphens) in the last phrase of his paragraph, and tell him not to be ashamed to put his name to his production. This superb experiment has been admired by the wise of the old and the new world, and celebrated by the able poets of our age. . . If this which has excited the curiosity of all classes of people, both in Europe and America, appears so trivial in his eyes, do request him to be kind enough to teach me how to realize Monsieur Bergerac’s novel, which sends his hero to the moon; or else tell him to shut up his Ebenezer." Blanchard had good reason to resent his treatment in the columns of the Oracle. The French émigré was one of the true pioneers of "aerostation" as balloon flight was then called. Born at Les Andelys, near Rouen, in 1753, Blanchard had demonstrated a precocious mechanical inventiveness and had always been fascinated with the possibility of human flight. Following the revolutionary hot-air balloon experiments of the Montgolfier brothers in 1783, Blanchard became a dedicated balloonist, quickly adopting the principle of filling his aerostat with "inflammable air" or hydrogen instead of the quickly exhausted "rarefied" (heated) air used by the Montgolfiers. Blanchard performed his first aerial voyage in March, 1784. His balloon was 27 feet in diameter and had a parachute suspended beneath it as a precaution in case it burst.

Blanchard had good reason to resent his treatment in the columns of the Oracle. The French émigré was one of the true pioneers of "aerostation" as balloon flight was then called. Born at Les Andelys, near Rouen, in 1753, Blanchard had demonstrated a precocious mechanical inventiveness and had always been fascinated with the possibility of human flight. Following the revolutionary hot-air balloon experiments of the Montgolfier brothers in 1783, Blanchard became a dedicated balloonist, quickly adopting the principle of filling his aerostat with "inflammable air" or hydrogen instead of the quickly exhausted "rarefied" (heated) air used by the Montgolfiers. Blanchard performed his first aerial voyage in March, 1784. His balloon was 27 feet in diameter and had a parachute suspended beneath it as a precaution in case it burst.