| Deceased Man Boosts Maine Economy |

SOUTH BERWICK HISTORY

SOUTH BERWICK HISTORY

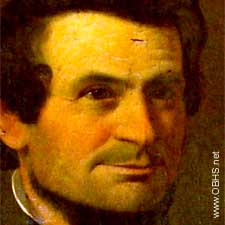

Why spend $5,000 to restore this old painting? South Berwick historians have a very good reason. Preserving John Lord Hayes (seen here) actually helps preserve Maine. New studies show that communities that care about their culture – about the arts and history -- are better off than communities that don’t. Read more.

WHO WAS John Lord Hayes?

John Lord Hayes is safe. His deteriorating portrait will be repaired by the Old Berwick Historical Society (OBHS). The Counting House Museum in Maine has received a grant of $2,500 to restore one of the only surviving portraits of a 19th century South Berwick citizen. Hayes is one of the lucky ones. His preserved portrait will go on public display.

Maine Secretary of State Matthew Dunlap says a recent report to the Maine Legislature indicated that many of Maine’s historical collections are deteriorating.

Dunlap and other Maine officials emphasize that the "creative economy" is an important factor in the state’s economic growth. Studies now show that cultural resources are important to people planning to locate new businesses or choosing a community in which to retire. Grants such as the one awarded the OBHS sustain the cultural history of this key sector of our economy, officials said. And cultural history is falling apart.

John Lord Hayes, a student at Berwick Academy in South Berwick, went on to an interesting career in Washington, DC. But he was not a Washington or a Jefferson, nor was his portrait painted by a famous national artist. So the painting has not gotten the best care over the years, a problem typical of many early artifacts.

"Maine has an estimated 200 million historical records and hundreds of thousands of historical artifacts, many in facilities with little or no security, fire protection, or environmental controls," says James Henderson, director of the Maine State Archives. "Recent surveys show that Maine people in local government, historical societies and libraries are seeking help to preserve our heritage."

Small grants have stimulated local citizens and organizations to commit more of their own resources to these projects, Henderson went on. "Although financial support is important, recognition of local concerns and effort through an award also generates a substantial amount of enthusiasm," he noted.

The Hayes painting is expected to cost a total of $5000 to restore, so to complete the work, the historical society must raise the balance of the funds. The other $2,500 was awarded by the Facilities Grants Program of the Maine New Century Community Program. During it’s first 150 years the painting was improperly cared for, repaired and displayed, a common problem with old objects. The costly restoration will make up for that.

"The original fabric support is thin linen, but it has been mounted onto a thick paper board backing with an unknown adhesive," said restorer Martha Cox of Shapleigh, Maine. "Some areas of the linen are not adhered and are bubbling and buckling away from the backing board. The canvas has been severely damaged with five major multiple-faceted tears through the background and jacket of the sitter. The damages have been repaired with additional adhesive that is visible on the surrounding paint surface. The tears have caused paint losses and planar distortion to the canvas surrounding the damages."

Cox will have to carefully remove the entire backing board and excess adhesive and paper fibers from the canvas. She will then locally consolidate the areas of flaking from the front of the painting to re-adhere and stabilize the fragile paint.

Artists, then as now, are an important part of the state’s "creative economy" says Henderson. "Grants of this kind support community efforts to protect the stories of our heritage and how we lived our lives. People want to understand the history of their communities."

The restored painting is a focal point of a new exhibit, "South Berwick’s Attic," opening in June. The unknown artist who painted John Lord Hayes was very likely a Maine or New Hampshire portraitist.

OUTSIDE LINKS: The Maine State Archives and Old Berwick Historical Society

MORE on JOHN LORD HAYES

RESTORING ART PROMOTES SOUTH BERWICK COMMUNITY (continued)

ABOUT JOHN LORD HAYES

John Lord Hayes was born in 1812 and grew up on Academy Street in what is today remembered as the Hayes House, residence of the headmaster of Berwick Academy. Hayes was a student in the 1820s when the academy was the area’s only secondary school, and his sister, Hetta Hayes, was one of the first girls ever admitted. Their father, Judge William Allen Hayes, was president of the trustees.

After studies at Dartmouth and Harvard Law School, the younger Hayes practiced law in Portsmouth and was appointed Clerk of the United States District Court in New Hampshire. A strong opponent of slavery, he became a leader in the Free Soil movement.

He became general manager of the Katahdin Iron Works Company of Maine. Later he was secretary of the Mexican, Rio Grande, and Pacific Railway Company, and in the 1850s helped organize the construction of a railroad across Mexico.

Moving to Washington, DC, Hayes rode in Lincoln's first inaugural parade. He became chief clerk in the United States Patent Office and the first president of the National Tariff Commission. Throughout his life Hayes authored several scholarly works, including a translation of Latin hymns from the early and middle ages published just before his death in 1887.

Art historians, including Tom Hardiman of the Portsmouth Athenaeum, have considered the possibility Hayes was painted by portraitist William Stoodley Gookin (1799-1873) of Dover, NH, and Saco, ME. Gookin had South Berwick ties and was related by marriage to Hayes’s sister. A known Gookin portrait is on display today at the Counting House Museum, and others at the Saco Museum. – Wendy Pirisg, OBHS