| Who Really Ran the Underground Railroad? |

NH BLACK HISTORY

Does the train to freedom tell the wrong tale about slavery? Popular tales of kindly white homeowners protecting anonymous blacks on the run does not tell the full story. History tells us that only about one percent of the four million enslaved Americans escaped during the Civil War, and mostly by other African Americans.

SEE our NH Black History section

Kids who come to see the Underground Railroad in Portland, Maine are often disappointed at first, says historian and peace activist Wells Staley-Mays. There is, of course, no railroad, and nothing runs underground -- not in Maine, nor at hundreds of proposed stops along a roughly defined network of escape routes for enslaved African Americans. Estimates vary widely. Between 30,000 and 300,000 blacks made the harrowing journey North or migrated West or South to Meixco from bondage in the 19th century.

"I tell them that 'underground' is a metaphor for 'illegal'," says Staley-Mays.

"We're going someplace illegal?" the kids ask. "Awesome!"

"Well, not exactly," the guide confesses.

Instead the students find themselves touring old homes and churches, poking into attics, outbuildings, and parking lots where buildings used to be.It's a hard concept to grasp. Nearly two centuries after the Underground

Railroad occurred, historians in Northern New England still debate -- who, what, when, where and how. I attended one of those debates a few years ago at the Unitarian Church in Concord, NH. Sixty-seven attendees gladly traded a perfect Saturday for uncomfortable metal folding-chairs, fluorescent lights, and the chance to dig beneath the facts and legends of the underground railroad.

Railroad occurred, historians in Northern New England still debate -- who, what, when, where and how. I attended one of those debates a few years ago at the Unitarian Church in Concord, NH. Sixty-seven attendees gladly traded a perfect Saturday for uncomfortable metal folding-chairs, fluorescent lights, and the chance to dig beneath the facts and legends of the underground railroad.

Portsmouth historian Valerie Cunningham opened the conference at 8:30 a.m.. In 30 years of exhaustive research on Portsmouth African-Americans, she has yet to document a single "safe" house in her hometown, she said. None of the 24 sites on her Portsmouth Black Heritage Trail are linked to the Underground Railroad, not yet. But now the federal government is getting on the black history train, offering grants and incentives to locate and promote Underground Railroad stops. Her curiosity about possible sites in Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont led to this conference.

Keynote speaker John Ernest, now at the University of West Virginia, sounded a sharp alarm. As a professor of African-American Studies, he sees a danger here. In the rush to uncover historical "stations" and "conductors" along slave escape routes, he implies, we may be losing more than we gain.

The Underground Railroad can be "a comforting way of talking about slavery," John Ernest says, perhaps too comforting. "I am concerned that this is becoming the official way of acknowledging the past."

The dramatic escape stories too often document the kindly white saviors of faceless generic slaves, he says. There is an emphasis on architecture and white abolitionism, rather than on the enslaved figures themselves. Dramatic successful escape stories focus away from the horrors of the institution of slavery, a brutal system of human bondage built into American tradition, religion and law. Railroad stories tend to travel south to north, Ernest says, rather than north to south, back to the origins of slavery in this country.

The fact is, according to Prof. Ernest, that most of the enslaved people who escaped found their own way out. Like abolitionist Frederick Douglass, slaves often went "underground", or incognito, and simply took a train. Maria Weems, a well known success story of the Underground Railroad, escaped north by dressing up as a black jack, a male sailor, and taking a public train.

CONTINUE with UNDERGROUND RAILROAD

BLACK HERITAGE OF NH (continued)

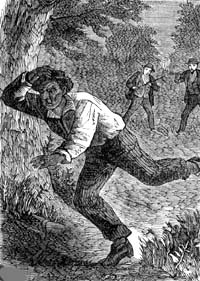

Fleeing from slavery on foot -- starving, scared and hunted -- Ernest reminds us, was "a journey of biblical proportions". Slaves had to travel enormous distances just to reach the northern outposts of the underground support system in Philadelphia, for example, making the treacherous southern leg of the sojourn alone. And the "freedom" blacks met upon reaching the fabled land of equality in Canada and the northern US, still contained a level of racism and discrimination intolerable today.

Mystery fuels the Underground RR. Its secrecy served a dual purpose, first by protecting the identities of those in the escape network, white and black. Secondly, black abolitionists like Frederick Douglass wanted southern slave owners to believe in an extensive, organized, well-funded popular network of "slave stealers". The more they feared the Underground Railroad, Douglass reasoned, the better.

In one of his three autobiographies, Douglass wrote that the southern slave owner should live in fear of "having his hot brains dashed out by an invisible agency." The less he said about the Underground Railroad, the more the legends grew.

How New Hampshire fit into this escape map is the focus of further research. Jody Fernald, a co-sponsor of the conference, presented her case for an Underground RR station in Lee, NH. Fernald has identified the Cartland house there, still privately owned. She has begun the extensive work of documenting the efforts of the Quaker family who lived there and were members of a "vigilance committee" that aided fugitive slaves.

Fernald’s evidence focuses on the escape of Oliver Gilbert, an enslaved black who left Maryland in 1848 at the age of 16. Authenticating the Lee site means tracking Gilbert’s trail possibly from Newbury, MA, through Kensington, to Lee and beyond. While in Lee, under the protection of Moses Cartland, Gilbert may have done farm work and built a stone wall. Anna and Phoebe Cartland may have taught him to read.

The Gilbert itinerary leads back to Boston where the fugitive spoke to white abolitionist groups, then off to New York in the 1850s where he married and had six children. Gilbert lived a rough and tumble life and turned up as a musician in Philadelphia during the Civil War. He made a pilgrimage back to Lee, NH in 1902. Fernald remains on the trail, accumulating data, making her case.

No one intends to diminish the struggle of white abolitionist in the decades-long battle to end American slavery. The Cartlands, for example, suffered condemnation from their Quaker elders. White abolitionist were arrested, mobbed, stoned, jailed, reviled, branded with a hot iron, and even killed. But their brave stories inevitably pale against the daily lives of the enslaved blacks. While thousands escaped, four million African-Americans remained enslaved in the South in the mid-1800s.

The fear, according to one conferee, is to avoid creating "Underground Railroadland", turning the history of racial struggle into a theme park. By authorizing "official" black history sites, the federal government is working hard to put together a jigsaw puzzle of an organization that never actually existed. The freeze-dried official synopsis may take us down a sidetrack. Will Underground Railroad web sites, texts, videos, guides and board games inspire children to learn more about what Douglass called "American Slavery"? Or will it provide only easy answers and a national treasure hunt for secret stairways and hidden tunnels?

Debbie Khadraoui is a seventh generation African-American whose family settled in Bath, ME in 1754. With Wells Staley-Mays and others, she has devoted the last few years to reconstructing the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Portland. It is the oldest standing African-American church in the United States. But authenticating an Underground Railroad site, she says, requires one thing -- "studies, studies and more studies."

But there is a benefit to this exhausting research, and perhaps to the promise of government funding and the income derived from cultural tourism. The more we study, the more we learn.

What we learn in Portland, according to Staley-Mays, is that Maine had a "freed" black population of 600 at this time. Portland was, after all, based on a rum economy, and many blacks served as mariners and dockyard workers. Others were typically barbers, hack or carriage drivers and used-clothing salesmen. It’s an odd combination of occupations, he says, unless you consider the kinds of jobs that might be useful in smuggling, transporting, and disguising fugitive slaves.

The facts are, not only did most escaped slaves make their own way out of the South, but most northern aid came from fellow blacks. There were white abolitionist engineers and conductors to be sure, like William Lloyd Garrison, but the workers on the Underground Railroad, by in large, were African-Americans -- and white women – who closely identified with their struggle for freedom. That is the picture we need to capture in our imaginations, a picture not often found in American history textbooks or on national monument plaques.

The Underground Railroad is built, not out of steel, but of iron-willed people – black and white. And when it finally pulls into New Hampshire again, our true job is to climb aboard and follow the stories back to the heart of slavery, where so many of America’s modern troubles began.

Copyright © 2006 by J. Dennis Robinson. Robinson is editor of SeacoastNH.com and a trustee of the Portsmouth Black Heritage Trail. All rights reserved. This piece originally appeared here in another form in 2000. Images from William Stills (1897) "The Underground Railroad: A Record of Facts, Authentic Narratives, Letters" available online from the Library of Congress "American Memory" web site.

READER RESPONSE TO UNDERGROUND RAILROAD

READER CORRECTION ON ANN MARIA WEEMS

I recently came across your site and your story about Ann Maria Weems. Because there were major errors in it I tracked down Professor John Ernest who had given the lecture the article was based on. He said the reporter had gotten the facts mixed up.

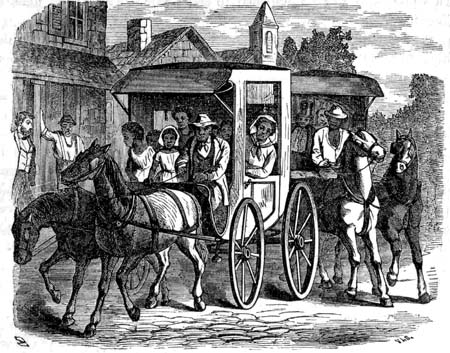

Ann Maria Weems did not escape on her own by dressing like a blackjack (a black sailor) and taking a train. She was only 15 at the oldest and had been a slave her entire life. Where would she have gotten a sailor's suit (it's actually a buggy driver's get-up) and the money to ride a train?

Her escape was a carefully laid out plan that involved black and white abolitionists on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line. My G, G, G, grandfather, Dr. Ellwood Harvey, was the man who took her from in front of the White House to Philadelphia and then NYC. This story has been told in several books: William Still's History of the UGRR; Elisa Carbone's Stealing Freedom, and Lorene Cary's Free. There will be a piece on Dr. Harvey in Main Line Today in the next month. You can also read about Dr. Harvey at the Yahoogroups site, The Amazing Ellwood Harvey, it's free, but you have to sign up for the site. Ellwood was a Quaker abolitionist, but partially undertook the rescue for the reward money. Even though he was poor Ellwood used the money to buy a dissection mannequin for the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania. It was the first college in the world for female doctors and very unpopular at the time. Therefore supplies were limited. The usual conductors in Washington DC were scared away from the rescue due to the high reward, $500, that Ann's master was offering for her return. That was in Sept. Ellwood couldn't come down until Thanksgiving break due to his teaching commitments. He brought her to Philly at Thanksgiving.

I would be willing to send any information I have if you would print the real story. There is another New Hampshire web site that has repeated the story you printed. I'd like to correct this mistake.

Because her entire family had been purchased and set free, but her owner refused to sell her, these abolitionists hatched a plan to help her escape. She eventually made it to Canada. A book on her whole family will be coming out soon.

Thanks for reading this,

Steve Harvey