| Prince Whipple and American Painting |

NH BLACK HISTORY

He was enslaved by a signer of the Declaration. He fought in the American Revolution. But Prince Whipple is very likely not the figure in the famous painting of George Washington Crossing the Delaware. But he does symbolize the fact that thousands of black men served in the American Revolution, even though they themselves would never known freedom.

READ: Untangling the Prince Whipple Legend

Who is the Black Crewman in "Washington Crossing the Delaware"?

JUMP to Leutz Painting History

JUMP to Sully Painting

JUMP to Currier & Ives

About Prince Whipple

On July 4, 1908, 125 years after the close of the American Revolution, a band of Portsmouth, NH veterans placed a marker in the North Cemetery. It was dedicated to Prince Whipple. A local newspaper account called him, "New Hampshire's foremost, if not only colored representative of the war for Independence."

Research for the Portsmouth Black Heritage Trail now suggests that as many as 180 New Hampshire blacks served in the Revolutionary War, either in the militia, even though this was against the law. The served in the Continental Army, or on privateer ships or in the fledgling navy. Prince Whipple's story, like most blacks of his era, is all but lost to history. Yet a symbol of his service endures in one of the nation's best known historical paintings. One black face is visible in both famous renderings of "Washington Crossing the Delaware." That one face represents thousands of African-Americans who fought diligently for freedoms they themselves would never enjoy.

For a time local historians believed that the black man in the hat was our own Prince Whipple. The facts, as it turns out, now indicate otherwise.

Prince Whipple's Story

He may have been an African prince, but that too seems unlikely. Scholars now know that many enslaved Africans were called "Prince". The use of noble titles and names from classical history – Cicero, Caesar, Pompey and others -- was more likely a way of separating slaves from the standard "Christian" names of members of the household. As in the case of Prince, the enslaved African was often given the surname of the household.

The few details known about Prince Whipple's life come from a passage in a breakthrough 1851 book entitled "Colored Patriots of the American Revolution," by William C. Nell. Nell documented the presence of blacks in the Revolution and helped prevent those stories from being lost. Nells information, however, was often anecdotal and subject to rumor, distortion and error. But in many cases, Nell is the only source we have. Of Prince Whipple he wrote:

Prince Whipple was born in Amabou, Africa, of comparatively wealthy parents. When about ten years of age, he was sent by them, in company with a cousin, to America to be educated. An elder brother had returned four years before, and his parents were anxious that their child should receive the same benefits. The captain who brought the two boys over proved a treacherous villain, and carried them to Baltimore, where he exposed them for sale, and they were both purchased by Portsmouth men, Prince falling to Gen. Whipple. He was emancipated during the [Revolutionary] war, was much esteemed, and was once entrusted by the General with a large sum of money to carry from Salem to Portsmouth. He was attacked on the road, near Newburyport, by two ruffians; one was struck with a loaded whip, the other he shot...Prince was beloved by all who knew him. He was the "Caleb Quotom" of Portsmouth. where he died at the age of thirty-two leaving a widow and children.

As was customary, Prince took the surname of his owner, William Whipple, who would later represent NH by signing the Declaration of Independence. Like many prominent whites, north and south, William Whipple was a slave owner. He married Catherine Moffatt and they lived in her father's mansion on the river in downtown Portsmouth, today one of the city's surviving historic houses. The slave quarters, where Prince, his cousin (or brother) Cuffy, and others likely lived, can still be seen.

When William Whipple joined the Revolution, Prince was forced to accompany him. According to a popular legend, William and Prince were in with General Washington on Christmas night 1776 during the legendary and arduous crossing of the Delaware. The surprise attack on the British forces was a badly needed victory for America, and for Washington's sagging military reputation.

In 1777 William Whipple was summoned to Exeter, promoted to Brigadier General. and ordered to drive British General Burgoyne out of Vermont. According to the story popularized by Portsmouth reporter Charles Brewster in the mid-1800s, Prince Whipple protested. "You are going to fight for your liberty," he reportedly said to William Whipple, "but I have none to fight for." General Whipple agreed to free Prince after the military campaign. The story, according to historian Valerie Cunningham, is likely imagined, created in the 19th century to make signer William Whipple look more sympathetic to blacks than he really was. Cunningham point oout that Prince was actually kept in service to the Whipple family for another seven years before his eventual release.

Prince married an emancipated woman from New Castle named Dinah in 1781. They and their children (including Ester Mollenoux, well known in 19th century Portsmouth) and relations eventually lived in a renovated two-story house on a lot just behind the Moffatt mansion. Prince's popularity may have come from being a jack-of-all-trades and master of ceremonies at local social functions where Cuffy Whipple, also enslaved by the Whipple family, was a popular musician.

In 1789, then President, George Washington toured Seacoast, New Hampshire and attended a party on his final night in Portsmouth. Brewster speculates that Cuffee Whipple performed on his fiddle and that Prince probably was in attendance. Washington, one of the nation’s largest slave-holders at the time, made no mention of such details in his voluminous journals. He would not have recognized Prince, not because he was among 2,000 men in his command during the famous crossing of the Delaware. But Prince, even if he was attending on General Whipple during the time of the battle, would have been 130 miles away with General Whipple in Baltimore.

Continue with PRINCE WHIPPLE

Washington Crossing the Delaware

"The Passage of the Delaware"

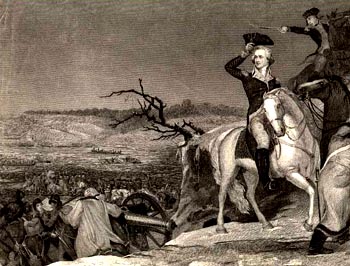

Painting by Thomas Sully, 1819

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Painter Thomas Sully was born in England, but grew up in South Carolina. He was scarcely a teenager when Prince Whipple died in Portsmouth, NH in 1796. By the time he came to paint the giant canvas (over 12 X 17 feet) of Washington at the Delaware River, Sully had become one of Philadelphia's leading portrait and figure painters. What Sully craved was to paint history. At this time, recreating authentic images of famous events was considered the highest calling of a portrait artist.

His opportunity came from the government of North Carolina. Excited by victory against the British in 1812, every state wanted to honor Washington. North Carolina wanted two copies of the popular Gilbert Stuart likeness for the new capitol building. Sully underbid his competition, offering to copy the Stuart picture for $400 and include an original Washington image of his own for $600. He got the job, but due to a communications breakdown, in 1819 Sully painted a canvas too large for the state capitol. He chose instead to tour the painting, but it turned out not to draw great crowds and he sold it for $500. It has, since then, spent most of its life in Boston, either rolled up in storage, or on exhibit. It currently hangs in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

In Sully's painting, Gen. Washington is on horseback, not standing in a wooden boat as later envisioned by Emanuel Leutze. Historical accuracy, as best it could be determined, was critical to Sully who exerted great effort to depict the precise details of the scene. He took pains to present Washington at his proper age, the "Durham" boats in the background, the precise dress and weaponry of soldiers. This makes his decision to include a single black trooper especially important. It is the closest the world will get, though imagined, to a portrait of a black Revolutionary hero.

Philipp P. Fehl (Art Bulletin, Vol. VL, No. 4, December 1973) suggests that the African-American in Sully's painting may be Washington's own slave William Lee. Washington called him "my mulatto man" and provided for him in his will. Fehl says Sully may have drawn the portrait of Lee from another painting, but notes that the black figure in Sully's work is a different face, a "more ideal representation." Interestingly, Prince Whipple, unlike William Lee, was described by his contemporaries as "a large, well proportioned man, and of gentlemanly manners and deportment." But Sully would have had no way of knowing Whipple or his description.

Historian Sidney Kaplan ("The Black Presence in the Era of the Revolution," National Portrait Gallery, 1975) supported the theory that Prince Whipple, indeed, is depicted in both paintings.

Continue with PRINCE WHIPPLE

Washington Crossing the Delaware

"Washington Crossing the Delaware"

Painting by Emanuel Leutze, 1851

Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC

Emanuel Leutze was born in Germany, and like Sully, came to America with his parents at an early age. They settled in Philadelphia where Sully was a well-known portrait artist, but Leutze spent half his life abroad. Trained in Dusseldorf, famous for its fine painting school, Leutze perfected the grand detailed historical painting style focusing first on tableaux featuring Christopher Columbus.

The story of his most famous and familiar work, "Washington Crossing the Delaware" plays like a TV mini-series. Like Sully, Leutze painted from live models and struggled for the utmost accuracy. A friend who posed for the body of Washington noted that the artist used almost exclusively Americans visiting in Germany in order to get accurate features. Unfortunately, details of costume, boat and weather conditions are not as recorded by history. The painting was nearly complete in Dusseldorf, when it was damaged by a fire in the studio. Though badly torn, the original was repaired and exhibited and eventually destroyed by Allied bombing of Germany in World War II.

The second image, the one now hanging in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, was painted in a large hall where Leutze and five other artists worked. Leutze's gigantic 20 by 16-foot canvas allowed for life-sized figures. A visitor to the hall noted that there was always a keg of beer behind the canvas and "a disposition to be jolly". The painters were so jolly, according to the account, that they purchased small cannons that they fired frequently, even shooting bullets until the inner walls of the German hall that was "fearfully scarred."

Plans to tour the painting in America proved successful as 50,000 visitors paid to see the work in New York late that same year. It was sold for $10,000 and exhibited in the Capitol Rotunda in Washington, DC. That success led Leutze to petition the US Congress in 1852 to paint a companion piece for the Capitol. It was more than a decade before his received a commission, but the popular subject this time was "Westward Ho," depicting America's westward expansion by wagon train.

In her detailed essay on the painting for the Met ("American Painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art"), writer Natalie Spasskey says the painting has gained a status nearly equivalent to a national monument. It has been copied, printed and exhibited continuously for nearly 150 years and the classic image shows no sign of losing favor. Spasskey accepted Sidney Kaplan's theory that the African-American depicted is Prince Whipple of Portsmouth, NH.

Continue with PRINCE WHIPPLE

Washington Crossing the Delaware

"Washington Crossing the Delaware"

By Currier & Ives

As with many American historical paintings, Americans usually saw, not the original, but an engraving or print. Most prominent were the often mangled copies by Currier and Ives. Both the Sully and Leutze paintings of Washington at the Delaware were sharply adapted by these popular printers in the late 19th century. Sully's Washington is completely turned around, his equestrian drama lost and his face aged 20 years to represent the familiar dollar-bill-George. In the cartoonish Currier & Ives representation of Leutze's classic boat scene, the river is now choked with iceberg-sized chunks and the crew has been greatly diminished. Not surprisingly, in both prints, the solitary black figure has been excised -- much as he and his race were carefully eliminated from the history or Revolutionary America until recently.