|

FRESH STUFF DAILY |

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

SEE ALL SIGNED BOOKS by J. Dennis Robinson click here |

||

New Hampshire historian Valerie Cunningham continues her groundbreaking study of African American roots in the Portsmouth seaport. This section looks at the limits of black freedom and looks at the well known "Negro Court". Valerie discusses hero Prince Whipple and his family and concludes with a look at women's social groups.

READ: PART 1, Blacks in Portsmouth Portsmouth shippers and merchants continued to capitalize on the escalating demands of the southern slave-based economy even as the reported number of slaves being held in New Hampshire was in decline. According to Benjamin Franklin: ... a considerable part of the slaves who have been sold in the Southern states since the establishment of the Peace have been imported in vessels fitted out in the state over which your excellency presides ...hope your influence will be exerted hereafter to prevent a practice which is so evidently repugnant to the political principles & forms of government lately adopted...which cannot fail of delaying the enjoyment of Peace & Liberty.... In 1789, Governor Langdon signed a bill passed by the New Hampshire House and Senate stating that "slaves cease to be known and held as property" in the state. This meant that the state no longer considered slaves to be taxable property; they had been assessed on a rating scale similar to that used for farm animals. While this did not end the practice of slavery, a compelling reason to free slaves was at hand. Portsmouth was experiencing a shift in its economic base and entering a recession. Owning slaves had become unprofitable. Under these circumstances slaves were increasingly able to negotiate their own freedom. However freedom was gained, slaves and free blacks were restricted by a social status which did not make an appreciable difference in the appearance of their lives or in the attitudes of whites toward them. The peculiarity for African-Americans in Portsmouth, as elsewhere, was that they were identified by white people as being part of the slave class long after winning their independence. Early laws which applied equally to free blacks and slaves were still in force. In the churches all blacks were required to sit together behind the white congregation or in the balcony. There is no evidence that free blacks could vote. Jobs, when available, were still limited to the most menial labor. A free black would not be hired if slave labor could be contracted with an owner. Housing possibilities were scarce for blacks; combinations of families and single people often shared households. The Portsmouth almshouse sheltered some free blacks who were unable to escape poverty. A man identified only as Quint died there at age 70, while Mrs. Silvia Gerrish was living at the almshouse when she and her three children were baptized. Dinah Wallis and her son also were baptized there. Violet Freeman died at the almshouse at age 75. Free blacks were unwelcome in other communities because the towns did not want to provide them with food and housing if they could not become self-supporting. Ultimately, the most horrifying risk facing a free black person was the possibility of being kidnapped at any time and being sold into slavery as a supposed runaway. In spite of the fear and danger, some blacks did leave Portsmouth. They might have searched for family members from whom they were separated during enslavement, or they could have been driven by a desire for a better life. Rapidly growing communities of free blacks in Boston, Newport and Philadelphia would have been attractive for the employment and educational opportunities made available through black organizations. Young adults especially if unmarried, might have sought a more stimulating social life than was available in JUMP AHEAD TO: Copyright (c) Valerie Cunningham. All rights reserved. This essay appears exclusively on SeacoastNH.com. First posted 1997. ABOUT THE AUTHOR African American Resource Center

Whatever problems they may have faced, Portsmouth blacks were able to participate in political and community-wide events. The Negro Court provides ample evidence of political activity among Portsmouth's black community. Much is unclear about this institution, but based on the available information, this "court", in existence during the latter half of the 18th century, seems comparable to others located in black communities elsewhere. These courts -- sometimes called "slave courts"- were based on African and European traditions, blended in a governing body which set the standards of behavior among its black constituency. Officers were elected annually by their peers. Apparently, officers consisted of men who not only were respected for the conduct of their own lives, but who also could be trusted to negotiate with white community leaders? A newspaper obituary for "King" Nero Brewster, slave of Col. William Brewster, described him as: A Monarch, who while living, was held in reverential esteem by his subjects -- consequently, his death is greatly lamented. Too little is known about the actual jurisdiction of the Court in Portsmouth but it appears that the body tried and punished blacks who committed minor offenses; one man who was tried for theft was prosecuted by the county court when he repeated the crime. Those who sat on the Negro Court were elected, by their peers, and election day for the Court was a particularly festive occasion. Servants, excused from work, dressed in their finest clothing and gathered at Portsmouth Plains to celebrate and vote. A regular convening of the Court was an occasion for exchanging news about friends and loved ones who lived outside the town; blacks also discussed the activities of white families with whom they had close contact. This kind of communication network was essential in slave societies for relaying vital information about their safety individually and as a community. The known leaders of the Negro Court in Portsmouth were among nineteen slaves who submitted a petition to the state legislature in 1779 urging the release of all New Hampshire slaves from bondage and to officially end slavery in the state. They appealed to the lawmakers' religious, moral and political sense of justice, but no legislative action was taken on the petition. It was tabled, and the entire petition appeared in the newspaper with an editorial disclaimer noting that its publication was "for the amusement" of the newspaper's readers. While some whites may have been entertained by the idea of slaves attempting to take control of their own lives, others must have sensed that blacks in Portsmouth could not be enslaved much longer. Continue FIRST BLACKS

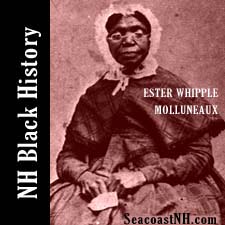

Prince Whipple was prominent among the slave petitioners. He was one of the few slaves whose name is known by those familiar with Portsmouth history. This recognition was not gained for his courage in petitioning for the end of slavery. Rather, his fame was based upon an earlier event, an agreement Prince is said to have made with his master, William Whipple: to fight in the revolution for the liberty of white colonists in exchange for his own emancipation. According to a much-quoted vignette (first appearing in Rambles About Portsmouth), Prince struck the bargain with Gen. Whipple and won his freedom immediately after the war. Yet, the harsh reality for Prince was that he gained his freedom seven years after the war for independence. Prince and another slave, Cuffee, were young children when they arrived in Portsmouth with some other slaves from Guinea about 1760. As the two boys reached maturity in the Whipple household, they became familiar with the customs and habits of Portsmouth's white gentry and visiting dignitaries. Prince served as chief steward for the most important social events in the town; Cuffee played violin for cotillions at the State House. In his position as the general's body servant, Prince would have been privy to conversations between the leading military and political thinkers of colonial America. Undoubtedly Prince knew about white fears of slave revolts in this country and in the West Indies; certainly, he learned from other blacks as he traveled that abolitionist activities were increasing in the major cities of the North. Prince probably was sophisticated enough to understand what was possible for blacks in Portsmouth which, in turn, undoubtedly earned him respect-and a leadership role -- among slaves. The wives of both Prince and Cuffee also had been slaves in families of comparable affluence, and, as a result, the women had acquired special skills which they used to enrich their family life and the community. Dinah, born a slave in the household of the Rev. Chase of New Castle, served the family until her emancipation at age 21. She married Prince and they had several children, one of whom was Ester Whipple Molluneaux. Ester, like her parents, was a member of North Church and a lifelong resident of Portsmouth. 74 Cuffee's wife, Rebecca Daverson, and their children shared a house with Prince and Dinah. From their home, the women taught black children of the town as part of the work of the Ladies Charitable African Society. These combined families used their skills and the respect they had earned among whites to benefit Portsmouth's black people. Continue FIRST BLACKS

The mere existence of The Ladies Charitable African Society implies the presence of knowledgeable leaders who were committed to improving the condition of blacks as slavery was ending. The name is a conscious identification with similarly named groups formed in other northern black communities during the period. The name of this organization is suggestive because these women were clearly engaging in an ethic of giving-similar to white charitable societies-while simultaneously practicing the centuries-old tradition of communal responsibility known in African cultures. The social work performed by these women, black and white, was of vital importance to the well-being of the community. Yet, black associations boasted a unique vision. A common notion held by most African-American service organizations was that local action on behalf of the individual ultimately strengthened all black people. This "universalist" view was consistent with African tradition and with the black American experience of constant struggle for small victories in a pervasively racist society. Many organizations catered to the special needs of free blacks, particularly those just emerging from slavery. In addition to classroom instruction, the Ladies Charitable African Society would have provided legal advice, employment references and opportunities for political networking through an exchange of information from all available sources. Because of the circumstances of slavery, black men were more tolerant of women activists than was generally true of the society at large. Although wives and daughters were customarily perceived as subordinate to men, women and men often worked as partners in meeting the needs of their particular communities. Experiences gained as participants in Portsmouth's Negro Court was undoubtedly valuable preparation for eventual freedom and self-government. On the surface, slavery in New Hampshire may appear milder when held up to the horrors of slavery in the Caribbean or deep South. Yet, bondage in Portsmouth was just as painful as bondage elsewhere. It is difficult to articulate the personal isolation which must have been experienced by the slave immigrants introduced suddenly, involuntarily and violently into a culturally alien world. Not only did blacks arrive on unknown shores speaking languages that were unfamiliar perhaps even to other Africans, but they came from different experiences in slavery, from various parts of Africa, the Caribbean and the American South. Slave women and men tried to preserve their dignity while accommodating the whims of self-appointed masters. They were multilingual, adding English to the African languages they brought with them; they ate strange foods and performed unfamiliar work; finally, they learned the social practices of this bizarre new world. The intellectual and spiritual integrity of centuries-old African civilizations was degraded and displaced in the traumatic process of enslavement. Africans became "American" in order to survive. The first blacks of Portsmouth are models of their persistence. Editor's Note: Valerie Cunningham has been researching, writing and teaching about local black history for 25 years. Her avocation has made her one of the region's experts and she is consultant to the Black History section of SeacoastNH.com. This article, complete with detailed footnotes, first appeared in Historical New Hampshire (Vol. 41, No. 4, Winter 1989) published by the NH Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission of the author. Copyright (c) Valerie Cunningham. All rights reserved. This essay appears exclusively on SeacoastNH.com. First posted 1997. Please visit these SeacoastNH.com ad partners.

News about Portsmouth from Fosters.com |

| Thursday, April 18, 2024 |

|

Copyright ® 1996-2020 SeacoastNH.com. All rights reserved. Privacy Statement

Site maintained by ad-cetera graphics

Stories

Stories

Valerie Cunningham has been researching, writing and teaching about local black history for 30 years. Her avocation has made her one of the region's experts and she is consultant to the Black History section of SeacoastNH.com. This article, complete with detailed footnotes, first appeared in Historical New Hampshire (Vol. 41, No. 4, Winter 1989) published by the NH Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission of the author. Valerie's work has inspired the Portsmouth Black Heritage Trail and her work is now recognized around the nation. Her new book,

Valerie Cunningham has been researching, writing and teaching about local black history for 30 years. Her avocation has made her one of the region's experts and she is consultant to the Black History section of SeacoastNH.com. This article, complete with detailed footnotes, first appeared in Historical New Hampshire (Vol. 41, No. 4, Winter 1989) published by the NH Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission of the author. Valerie's work has inspired the Portsmouth Black Heritage Trail and her work is now recognized around the nation. Her new book,