|

FRESH STUFF DAILY |

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

SEE ALL SIGNED BOOKS by J. Dennis Robinson click here |

||

Page 1 of 4

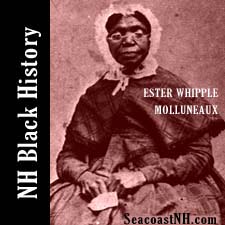

New Hampshire historian Valerie Cunningham continues her groundbreaking study of African American roots in the Portsmouth seaport. This section looks at the limits of black freedom and looks at the well known "Negro Court". Valerie discusses hero Prince Whipple and his family and concludes with a look at women's social groups.

READ: PART 1, Blacks in Portsmouth Portsmouth shippers and merchants continued to capitalize on the escalating demands of the southern slave-based economy even as the reported number of slaves being held in New Hampshire was in decline. According to Benjamin Franklin: ... a considerable part of the slaves who have been sold in the Southern states since the establishment of the Peace have been imported in vessels fitted out in the state over which your excellency presides ...hope your influence will be exerted hereafter to prevent a practice which is so evidently repugnant to the political principles & forms of government lately adopted...which cannot fail of delaying the enjoyment of Peace & Liberty.... In 1789, Governor Langdon signed a bill passed by the New Hampshire House and Senate stating that "slaves cease to be known and held as property" in the state. This meant that the state no longer considered slaves to be taxable property; they had been assessed on a rating scale similar to that used for farm animals. While this did not end the practice of slavery, a compelling reason to free slaves was at hand. Portsmouth was experiencing a shift in its economic base and entering a recession. Owning slaves had become unprofitable. Under these circumstances slaves were increasingly able to negotiate their own freedom. However freedom was gained, slaves and free blacks were restricted by a social status which did not make an appreciable difference in the appearance of their lives or in the attitudes of whites toward them. The peculiarity for African-Americans in Portsmouth, as elsewhere, was that they were identified by white people as being part of the slave class long after winning their independence. Early laws which applied equally to free blacks and slaves were still in force. In the churches all blacks were required to sit together behind the white congregation or in the balcony. There is no evidence that free blacks could vote. Jobs, when available, were still limited to the most menial labor. A free black would not be hired if slave labor could be contracted with an owner. Housing possibilities were scarce for blacks; combinations of families and single people often shared households. The Portsmouth almshouse sheltered some free blacks who were unable to escape poverty. A man identified only as Quint died there at age 70, while Mrs. Silvia Gerrish was living at the almshouse when she and her three children were baptized. Dinah Wallis and her son also were baptized there. Violet Freeman died at the almshouse at age 75. Free blacks were unwelcome in other communities because the towns did not want to provide them with food and housing if they could not become self-supporting. Ultimately, the most horrifying risk facing a free black person was the possibility of being kidnapped at any time and being sold into slavery as a supposed runaway. In spite of the fear and danger, some blacks did leave Portsmouth. They might have searched for family members from whom they were separated during enslavement, or they could have been driven by a desire for a better life. Rapidly growing communities of free blacks in Boston, Newport and Philadelphia would have been attractive for the employment and educational opportunities made available through black organizations. Young adults especially if unmarried, might have sought a more stimulating social life than was available in JUMP AHEAD TO: Copyright (c) Valerie Cunningham. All rights reserved. This essay appears exclusively on SeacoastNH.com. First posted 1997. ABOUT THE AUTHOR African American Resource Center

Please visit these SeacoastNH.com ad partners.

News about Portsmouth from Fosters.com |

| Friday, April 19, 2024 |

|

Copyright ® 1996-2020 SeacoastNH.com. All rights reserved. Privacy Statement

Site maintained by ad-cetera graphics

Stories

Stories

Valerie Cunningham has been researching, writing and teaching about local black history for 30 years. Her avocation has made her one of the region's experts and she is consultant to the Black History section of SeacoastNH.com. This article, complete with detailed footnotes, first appeared in Historical New Hampshire (Vol. 41, No. 4, Winter 1989) published by the NH Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission of the author. Valerie's work has inspired the Portsmouth Black Heritage Trail and her work is now recognized around the nation. Her new book,

Valerie Cunningham has been researching, writing and teaching about local black history for 30 years. Her avocation has made her one of the region's experts and she is consultant to the Black History section of SeacoastNH.com. This article, complete with detailed footnotes, first appeared in Historical New Hampshire (Vol. 41, No. 4, Winter 1989) published by the NH Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission of the author. Valerie's work has inspired the Portsmouth Black Heritage Trail and her work is now recognized around the nation. Her new book,